279

●

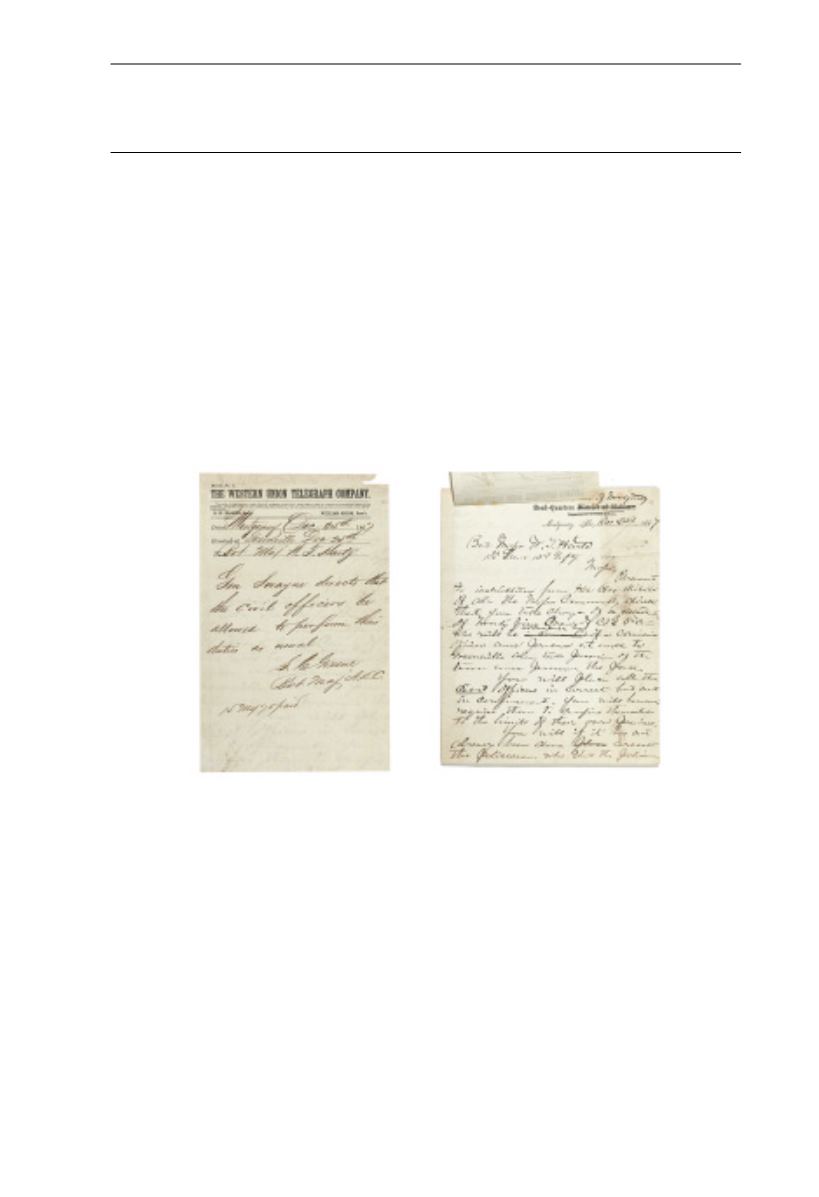

(RACE RIOT.) SWAYNE, MAJOR GENERAL WAGER.

Documents order-

ing the arrest of a policeman for the shooting of an unarmed black man, and

placing local civil officers under arrest.

Two partially printed documents, accom-

plished by hand: Western Union Telegraph and Headquarters, District of Montgomery.

Signed by Maj. General Swayne’s Aide de Camp, S. C. Greene.

Alabama, 1867

[2,500/3,500]

Major General Wager Swayne (1829-1902), president of the Alabama Freedmen’s Bureau, orders a

detachment of twenty-five men of Company G, 5th Cavalry to round up and arrest a number of civil

officers, and the policeman who shot an unarmed black boy. It seems a group of white boys were play-

ing and tossed a firecracker at the head of a negro boy, who then reciprocated by hitting the white boy

with a stick. The boy’s father, Mr. Morgan, a policeman, determined that the boy had indeed struck his

son, produced a pistol and fired two shots, the second one to his back killing the boy. A local newspa-

per observed that “the Negroes then became very much excited, and would not be quieted or listen to

reason.” Demanding the whites hand over the policeman, a riot seemed sure to follow—-all of this on

Christmas Eve! The local military official (the author of the telegram offered here) called for troops,

and the arrests, all according to the present documents. The article, a Xerox of which accompanies these

documents, describes the rest of the proceedings.

CIVIL RIGHTS

LOTS 278-337

279

278

●

(CIVIL RIGHTS.) KELLEY, WILLIAM DARRAH.

Why Colored People in

Philadelphia are Excluded from the Street Cars.

27 pages. 8vo, modern marbled

paper-covered boards with morocco label up the spine; original front wrapper bound in.

Philadelphia: Benjamin Bacon, 1866

[800/1,200]

FIRST EDITION

.

“January 7, 1866 was reputed to be one of the coldest days recorded in

Philadelphia; the thermometer at the Merchant’s Exchange fell to below zero. This was no colder than

the reception of the Negro veterans of the War who found that they had been permitted to serve in the

army but could not ride the trolleys in Philadelphia. Some violence, but much embarrassment fol-

lowed.” After appeals to “Liberality, Benevolence and love of Freedom” had fallen on deaf ears,

lawyer-abolitionist Horace Binney wrote to the capital: “Colored people pay more taxes than is paid

by the same class in any other Northern city.” Finally the Legislature in Harrisburg, no friend to the

Negro or Philadelphia, ruled that Negroes could ride the trolleys in the “City of Brotherly Love.”

The irony of this act of desegregation was that Harrisburg did it to spite Philadelphia liberals. Negro

History, #172; Blockson 4375; Afro-Americana 5505.