The Studio Assistant: Louise Nevelson & Teddy Haseltine

Our June 25 sale of Contemporary Art features a run of prints by Louise Nevelson. Behind great artists are studio assistants equally devoted to their craft. For Nevelson one of those assistants was Teddy Haseltine. Meagan Gandolfo, one of our cataloguers for the prints and drawings department at Swann Galleries, takes us through the collaborative relationship between Nevelson and Haseltine throughout her career.

Theodore “Teddy” Haseltine

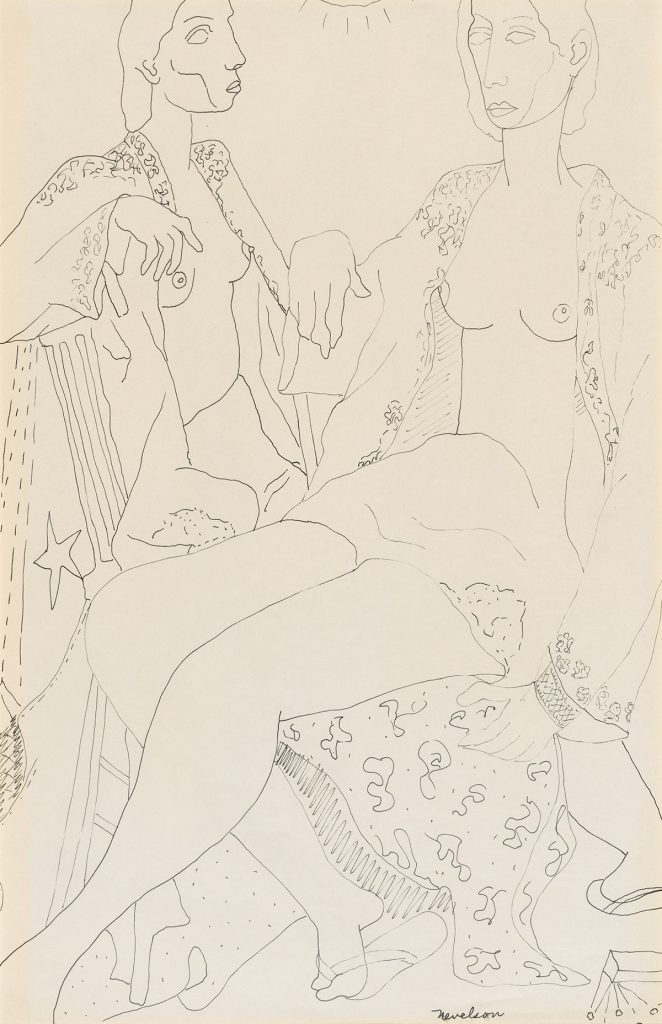

Theodore “Teddy” Haseltine, a young artist, was introduced to famous sculptor Louise Nevelson through a mutual friend, sculptor Donald Mavros in the early 1950s. Nevelson, born in present-day Ukraine and raised in the United States, studied at the Art Students League of New York from 1929 to 1930, with artist Hans Hofmann and Diego Rivera. Through the 1930s, she gained attention for her early, Cubist-inspired sculpture and in 1941 received her first solo exhibition at Nierendorf Gallery, New York. She would become a central figure in the fields of sculpture and conceptual art and exhibit at the 1962 Venice Biennale.

Though in the 1950s, Nevelson worked tirelessly to develop her unique, recognizable style. During this time in Nevelson’s life, she depended heavily on her assistants and her small circle of friends to insulate her from the outside world. She struggled financially and strove to gain notice overseas. When Nevelson found herself without an assistant in 1952 in New York, she offered the position to Haseltine. For the next 12 years, Haseltine served as Nevelson’s trusted confidante and she took on a maternal role in his personal and professional pursuits, often rivaling Nevelson’s biological son sculptor Mike Nevelson. Haseltine’s devotion and support withstood Nevelson’s tumultuous relationships with gallerists and the ebb and flow of her career. Haseltine’s exuberance matched Nevelson’s vibrant personality. He enjoyed the freedom to smoke, drink, dance, and listen to music in Nevelson’s studio, where they both worked long hours.

Louise Nevelson at Atelier 17

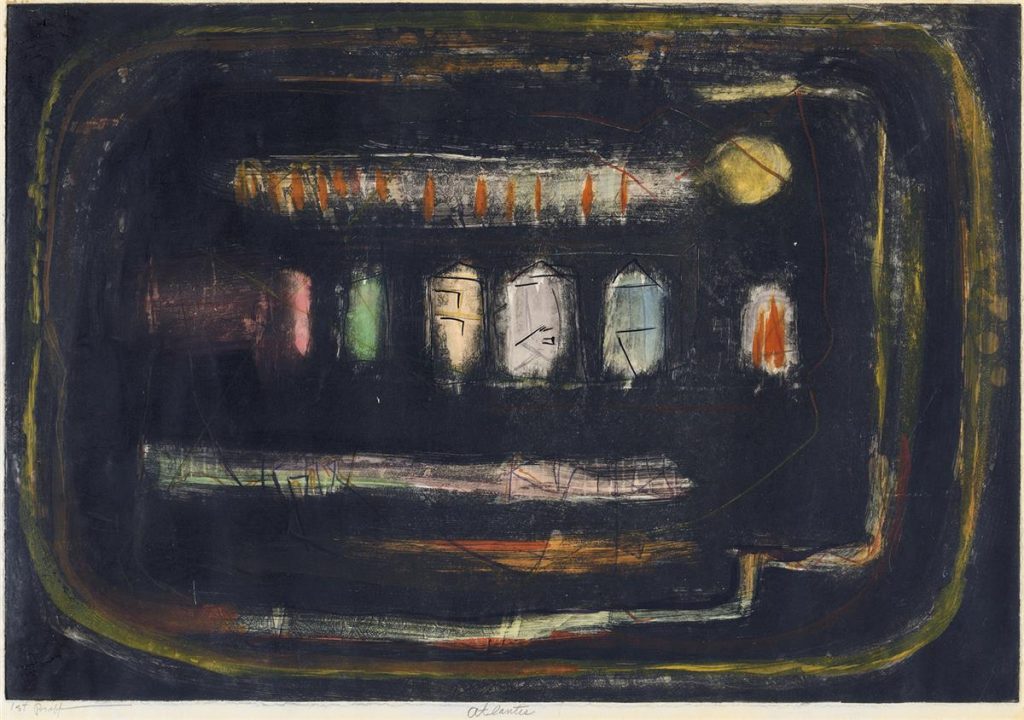

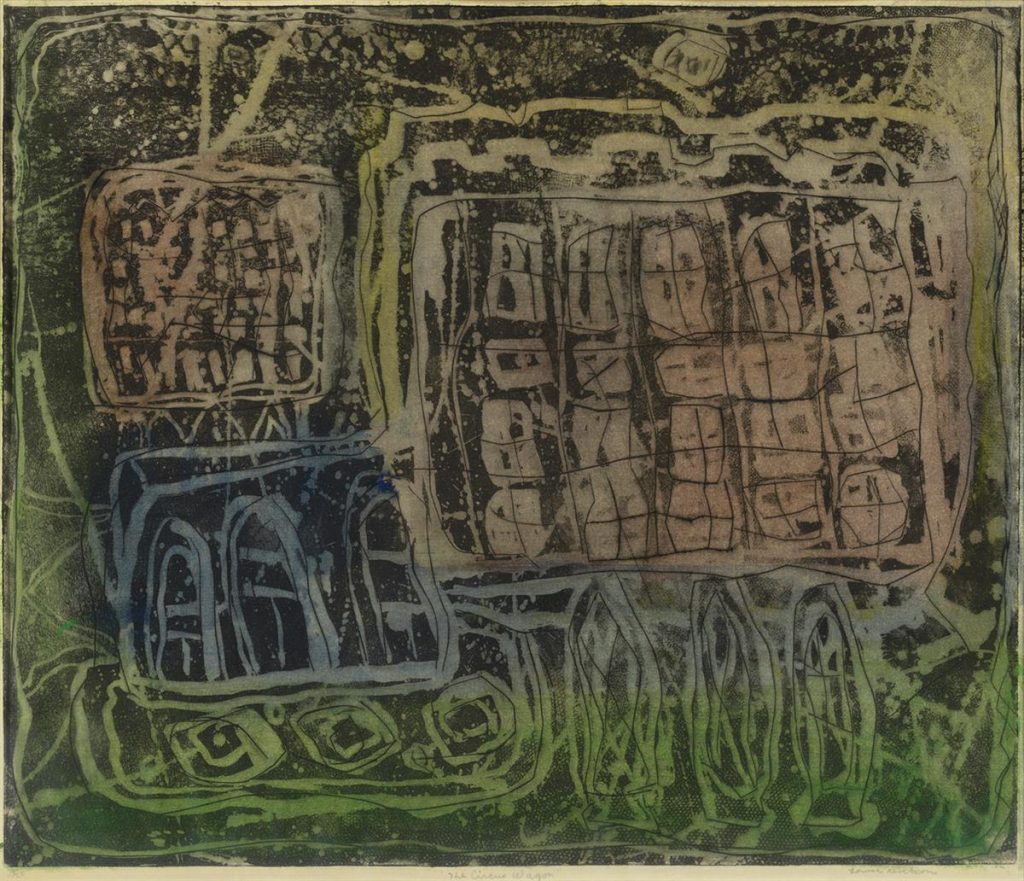

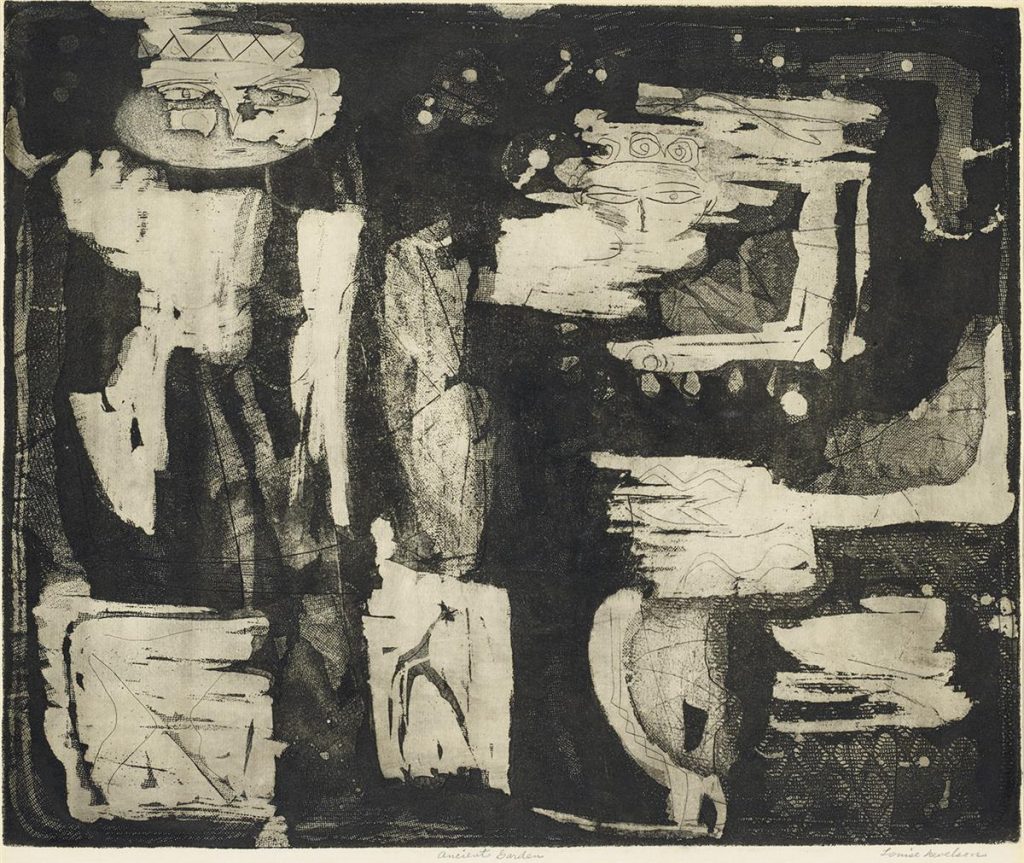

From September 1952 through May 1953 and again in the fall of 1954, Nevelson and Haseltine worked at the print workshop Atelier 17 in New York. In the 1940s, Nevelson briefly worked in etching but did not like the strict technical aspects of the medium taught under Stanley William Hayter. After the transfer of directorship to Peter and Florence Grippe, Nevelson was invited back with the promise that she would be shown how to create etchings with unconventional tools. Nevelson used the soft-ground etching technique paired with vintage lace, fabric, and rudimentary sharp objects like a can opener to texturize her large etching plates. After the first acid bath, she would further scratch into the plate. In her most innovative impression, Moon Goddess II, Nevelson continuously added and moved ink around the plate using a paintbrush. Her bold prints, usually characterized by intricate patterns and darkness were inspired by her time in Central America and the area’s culture. They were admired by artist Dorothy Dehner, who became close friends with Nevelson. Previously, Haseltine was trained by Dehner to operate a printing press during Dehner’s time living in Bolton Landing, New York.

Dehner remembered that Haseltine usually “turned the wheel” for Nevelson and he and Nevelson worked feverishly on Nevelson’s newfound medium (in a 1970 interview, Nevelson would claim that she operated the press independently). Florence Grippe claimed that Nevelson had spent the equivalent of about two month’s rent on etching supplies in only a few months at Atelier 17. In October 1954 alone, Nevelson produced 29 plates and hundreds of impressions. She had dedicated many of her early proofs to Haseltine and his partner, photographer and WWII veteran Albert Argentieri. Her Atelier 17 works culminated in her first solo exhibition in eight years, Louise Nevelson: Etchings at Lotte Jacobi Gallery, New York in 1954. Nevelson’s fixation on the heavy black ink of the etchings would return often in her future work.

Move to Spring Street & Development of Nevelson’s Cathedrals

In 1956, Haseltine moved into Nevelson’s home and traded his work for boarding. He accompanied Nevelson’s move to Little Italy’s Spring Street in 1958 and played a role in convincing her to leave the emotional safety of her beloved condemned brownstone on 30th Street. The two artists were in constant collaboration with each other and Haseltine’s free spirit was said to have rekindled the mid-career artist. Haseltine and Argentieri helped gather materials for her landmark wooden sculptural walls (“cathedrals,” the first of which exhibited in 1958) which rivaled the other artists’ large scale Abstract Expressionist canvases. Haseltine and Argentieri would search for material in abandoned buildings in New Jersey together. Haseltine would saw and hammer away at the found material after Nevelson laid out the construction. Argentieri photographed Nevelson’s studio and art. Over the years of their friendship, Nevelson would gift him some of her prints and drawings.

Nevelson in the 1960s

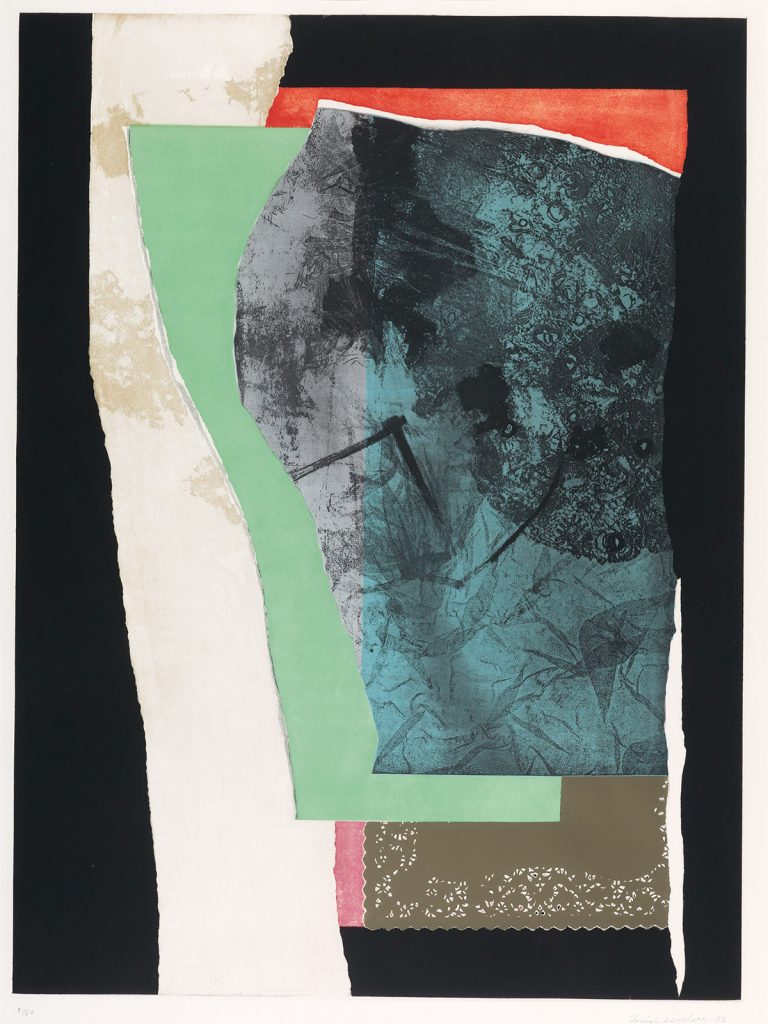

The 1960s found Nevelson in legal turmoil involving gallery contracts and real estate. Haseltine also began the years of the new decade experiencing his own personal troubles as his relationship with Argentieri had ended. Haseltine and Nevelson both went through a period of easing their depression with drinking. Nevelson’s career had plummeted alongside her mood. In April 1963 Nevelson traveled to Los Angeles at the request of the Tamarind Workshop and produced a cathartic series of lithographs. During her three months away, Nevelson received positive reports from her son who visited Haseltine in New York. Nevelson transformed her outlook and returned to New York reinvigorated.

By that winter, Haseltine’s health was failing and the following summer he had to undergo an operation (presumably due to heavy drinking). In August, though originally thought to be in recuperation, he collapsed in Nevelson’s bedroom and reportedly died of a cerebral blood clot. Nevelson dealt with Haseltine’s death with her common tactic of insulating herself and declined to attend her assistant’s funeral and avoided talking about him entirely. Haseltine’s funeral was held in Hudson Falls, New York, where Argentieri had arranged for him to be given a Roman Catholic burial next to his mother. Nevelson’s biographer, Laurie Wilson, PhD, suspects that Nevelson’s work on Homage to 6,000,000 dedicated to victims of the Holocaust, was part of the artist’s private grieving process.

From 1965 through 1966, Nevelson made the decision to have her Atelier 17 experimental plates reprinted by Emiliano Sironi at the Hollander workshop. Though the original Atelier 17 prints have more of an expressive, bold quality, Nevelson’s Hollander edition gained more popularity. Nevelson spontaneously re-titled the etchings as she saw them being printed. Her titles were based on what she saw in the image at that time. With a decade more of life behind her, Nevelson saw a new vision in these prints. In 1965, Nevelson donated several of her original Atelier 17 works to the Brooklyn Museum in Haseltine’s memory. Argentieri’s Nevelson prints, each unique in the artist’s additions, remained with his family.

Browse the full run of works by Louise Nevelson, at auction June 25, 2020.

Do you have a work by Louise Nevelson we should look at?

Learn about how to consign to an auction, and send us a note about your item. Browse past lots and prices realized for pieces by Louise Nevelson at Swann Galleries.