Beyond the Bestiary: Fantastic Beasts and Figures of Myth in Old Master—and Modern—Prints

Medieval bestiaries were illustrated catalogues of creatures both real and imagined, detailing physical descriptions, origins, and symbolism of each beast that identified the vices and virtues of society. Originally created for Christian inspiration, bestiaries evolved into sources of entertainment for those who could afford to have a volume made. These books were inspired by ancient writings, myths, and Biblical references. Prolific in the art of the Old Masters, like Albrecht Dürer, these beasts and the symbolism behind them have survived and evolved through the centuries into Modern and Contemporary Art in western culture. Some symbolic meanings are clear (the lamb for Christ’s sacrifice, humility; a dove for peace, hope), but the meanings of others, as the imagination wanders, are far more elusive.

Albrecht Dürer’s Menagerie

Familiar animals served as significant symbols in Old Master artworks, especially those by Albrecht Dürer. Rabbits served as symbols of fertility and abundance. Hares are placed at the foreground of Dürer’s The Holy Family with the Three Hares, conferring the blessing of a large Christian family. The number of hares is also significant as it represents the Holy Trinity.

In Dürer’s Virgin and Child with the Monkey, the infant Jesus and the Virgin Mary are joined by a more exotic creature. Monkeys would have been known in Europe during the early sixteenth century, as the wealthy kept them for their private menageries. Monkeys symbolized the basest of human instincts and vices. Without a human conscience, monkeys were creatures of greed, malice, and lust. When pictured next to the Virgin and Child, the monkey’s natural inclinations are subdued, just as the Holy Presence subdues the same in men. Over 400 years later, Benton Spruance explored man’s primitive side in Introduction to Love, a scene of a couple after a tryst. A monkey observing from atop a chair creates the possibility that this meeting is a lustful exchange rather than a sweet romance. The vulture and a group of small snakes are also part of the composition, symbolizing impure, evil thoughts, and temptation respectively.

The snake appears in numerous Old Master works as a symbol of Original Sin, the subject of Dürer’s Adam and Eve. The beasts present in Adam and Eve are a parrot, rabbit, mouse, cat, elk, ox, and mountain goat. In Dürer’s universe, the parrot was associated with the Annunciation, salvation, the Virgin Mary, and miracles. The goat symbolizes primitive instincts and damnation, prevalent in depictions of the devil. The four humors are represented by the rabbit (sanguine, sensual), cat (choleric, femininity, quick-tempered), elk (melancholic, irascible), and ox (phlegmatic, calm). The mouse, in contrast to the cat, represents masculine weaknesses which succumb to evil. It was Dürer’s belief that man embodied all of these personality traits to achieve balance. Some of these same animals resurface in modern depictions of Adam and Eve.

The Cat Through Art History

Perhaps the most multifaceted and evolving animal symbolic representation is that of the cat. Their larger cousin, the lion, was appointed by Adam in the Naming of the Animals to be king of the bestial hierarchy and the creature’s symbolism has not delineated. The domestic cat, however, has a varied symbolic history. Historically, the cat represented laziness, as it tends to sleep in the day and hunt at night, a sign of the devil. Today, they are still used alongside representations of witches and villains (think James Bond villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld’s companion). The cat is characterized as quick-tempered and fast to attack, as the predatory cat pounces on prey. The cat also symbolizes femininity and lust. In Manet’s scandalized Olympia, a small black cat sits on the edge of nude artist Victorine Meurent’s bed as she boldly looks at the viewer. The French public assumed the sitter was an urban sex worker soliciting a lapse in morality. In stark contrast, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, which was modernized in Olympia, shows a dog on the edge of the bed, a symbol for fidelity.

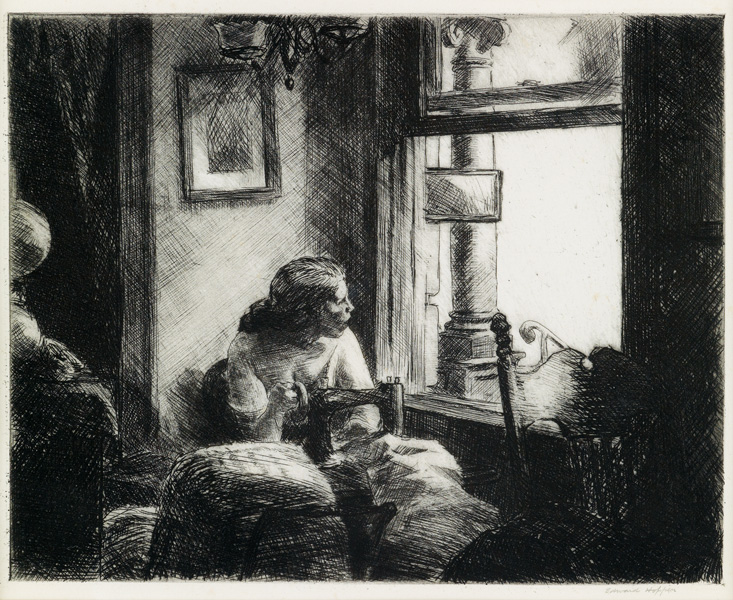

Being that cats have been negatively looked upon in the history of western culture, it may come as a surprise to find that the cat is commonly pictured next to the Virgin Mary in Annunciation scenes. The predatory nature of the cat in this context is a much more positive asset. The Annunciation comes with the expectation that Christ will imprison the Devil as a cat traps a mouse. The cat also represents domesticity, highlighting Mary’s humble life before being chosen. Later, as cities modernized, cats became both pampered female companions and, as strays, the commonplace outsiders of urban life. Jonathan Borofsky’s Berlin Dream is a great example of how urban cats are viewed. The predatory feline is seen outside from a window.

The Dog’s Role

In contrast, the dog’s place in western art history has been as steady as the cat’s has been turbulent. The dog has long been considered a trusty guardian and a loyal companion. Some dogs were trusted to be put to work as messengers, herders, turnspits, and hunters. Small dogs were used as lapdogs for the wealthy. Dogs show up frequently underfoot in Dürer’s engravings. In The Visitation, the dog represents faith and companionship. The same dog appears in The Flagellation, suggesting that Christ did have loyal followers even when surrounded by enemies. It has been suggested that the recurring depiction of the specific breed is possibly a portrait of the artist’s own dog. “Man’s best friend” also appears in Dürer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil as a sign that as the courageous knight rides past the goat-headed devil, his faith makes him fearless as his trust in God protects him. In Raimondi’s Judgment of Paris, the dog alludes to Paris’ shepherdic upbringing. The dog has had the same significance in later art. As a guardian, a dog watches over a young girl completing her chores in Thomas Hart Benton’s The Farmer’s Daughter. The dog in Les Saltimbanques also stands next to the child and acts as a noble companion even to these itinerants. Even Jeff Koons’ 43 foot tall Puppy was meant to inspire optimism and security in Germany in 1992. It now stands guard at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain. We also note a small dog as a status symbol and a nod to domesticity in Villon’s Le Potin and La Femme au Chien Colley, and in Cassatt’s Mathilde Feeding a Dog.

Cattle as a Symbol for Truth and Power

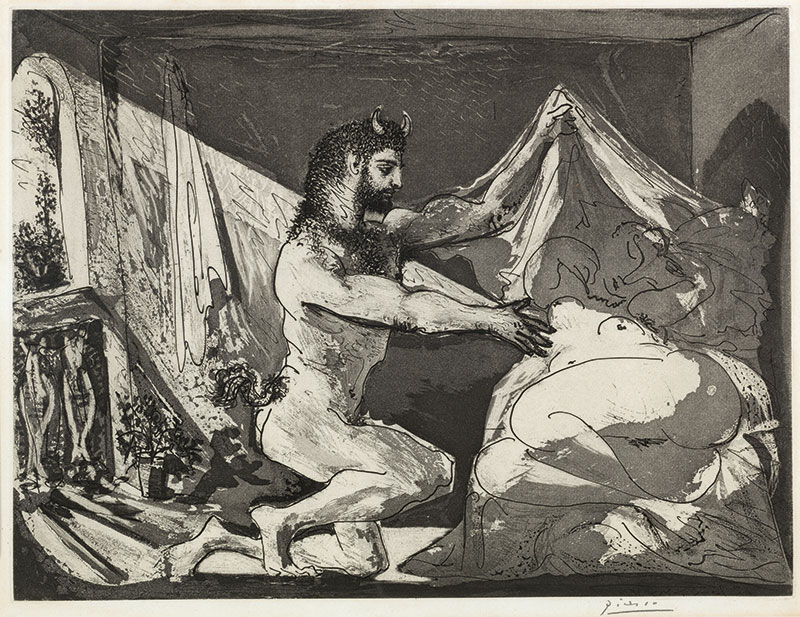

Another familiar animal is the cattle which often stands for truth. In Rembrandt van Rijn’s Christ Driving Money Changers from the Temple, it is stressed that Christ drove livestock dealers from the temple, indicating the sacrificial status of cattle in Judaism. The action of removing the cattle from the temple means that Christ had come to claim “his father’s house”. The cattle are both representative of this Christian truth and the rejection of Judaic practices. A calf signifies innocence, which Thomas Hart Benton uses in his print White Calf. Benton’s scenes from Martha’s Vineyard often depict the simplistic life on the isolated island’s farms and the honest labor needed. The bull has long been a symbol of strength and male virility. Goya, and later, Picasso, used the bull to convey moving scenes of masculinity and power, and the imminent danger of bullfighting. This display of machismo would carry into Picasso’s spiritual connection to bulls and minotaurs, bull-human hybrids. Picasso would frequently use these beasts to connote a male presence in a composition.

Mythical Beasts and Beyond

Minotaurs, unicorns, and dragons are perhaps the most well known mythical beasts today. According to medieval bestiaries, unicorns could only be caught by hunters if they laid their heads on a lap of a maiden. Unicorns eventually became synonymous with maidenhood, purity, and virtue. The latter two qualities linked the unicorn to Christ and the destruction of all sins (unicorn horns were antidotes for all poison). Though not congruent with accepted mythology, the maiden goddess Proserpine is abducted by Pluto on a unicorn in Dürer’s etching of the subject. Today, unicorns are still associated with a more childlike brand of innocence, magic, and wonderment. John Wesley’s Dream of Unicorn screenprint plays on the mysterious quality of dreams and ancient descriptions of “unicorns” that scholars now attribute to rhinoceroses. The bikini-clad woman acts as a foil for the maiden trope. In this print, nothing is as it seems. Damien Hirst also experimented with the form in The Dream where he constructed his own unicorn, preserved in formaldehyde, in 2008. On the other hand, dragons have long been seen as enemies and symbolic of the devil and evil. St. George slaying the dragon was a popular subject in Christian art and was later adopted by Salvador Dali.

Hybrid animals were also considered evil, combining the most fearsome parts of animals. These were usually vehicles of moral messages and allegory. It is not a mistake that the Bible’s Book of Revelation features two of the most loathed creatures. Dürer took the Bible verse literally in his woodcut and depicts two most imaginative creatures: “a beast come up from the sea with ten horns and seven heads, and upon his horns ten crowns, and upon his heads the names of blasphemy… And then I saw another beast coming out of the ground, and he had two horns like a lamb and spoke like a dragon.” These beasts represent false prophets and deceitful political powers who demand worship. Hybrid, otherworldly animals bring to mind the work of Dali again. Dali’s elephants, with long spindly insect-like legs, are impossibly supportive even while carrying symbols of power like the obelisk and howdah. Dorothea Tanning’s self portrait Birthday is another example of an artist’s personal symbolic vocabulary. A winged lemur sits at Tanning’s feet, a creature of the artist’s dark spiritual realm. As a primate, the lemur also adds to the work’s underlying sexuality.

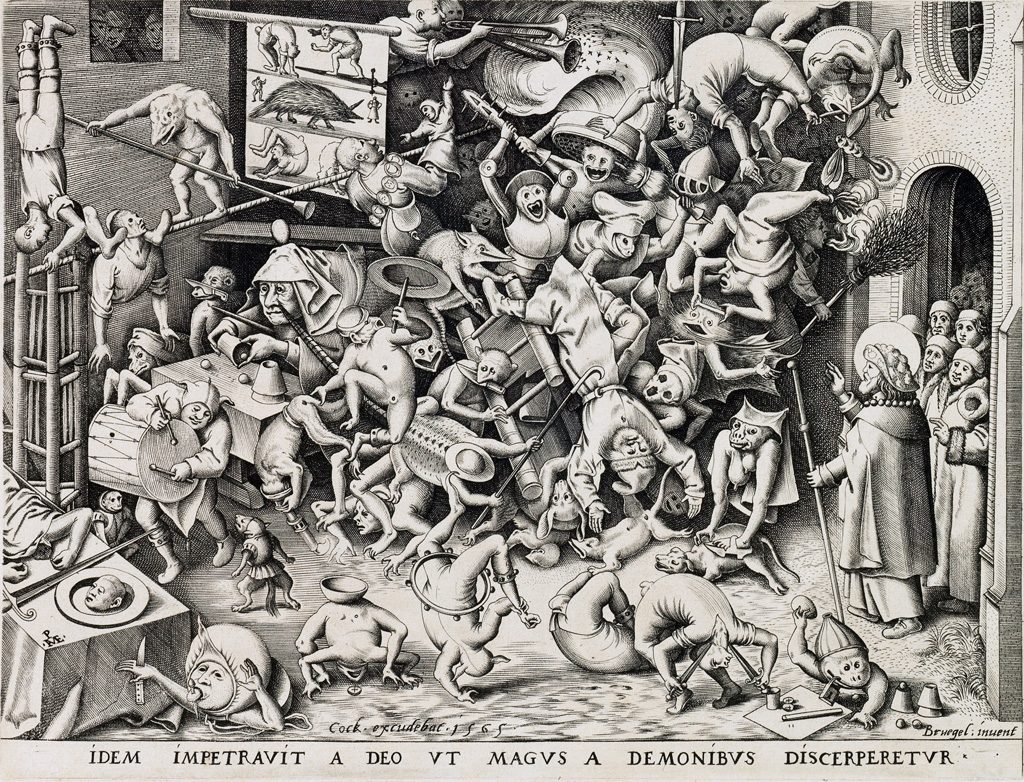

Bruegel was the master of human hybrids, also serving as cautionary figures of impurity and imbalance. Mortal weaknesses and vices disfigure Breugel’s human figures and hold a mirror up to our own shortcomings. Some characteristics may have also been borrowed from exaggerated and fictionalized travel accounts of exotic people and lands. A modern and well-known example of a human-animal hybrid is Max Ernst’s Loplop, his birdman alter-ego. Loplop was the way Ernst saw himself: a type of free spiritual creature with antisocial tendencies not bound to anyone or any place.

Throughout the history of western art, beasts real and imagined have been employed by artists to convey messages using a universal understanding of symbolism. These meanings have become more secular in modern times and are sometimes used as metaphorical identities. The medieval bestiary has also survived, given a revival by artists such as Raoul Dufy and Alexander Calder.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=OlBShB8qEWAQ7kNvwHbrXqd&_nc_oc=Adn09Fh3YL-11OkpQcrYGgFN9beLpm0IfGUn2bwN7iJs6d4v8qMeP8kSYmCw82y2ewU&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=tAw7REYwZZLTJH2gYFDRIA&oh=00_AfFntE5BpdhgoGI95lZi2PLq4mMH4VrDzFOq34kH3ACHug&oe=681B8F91)