The Original Beaver Map & Its Legacy

Tucked into the top left corner of an eighteenth-century map in our June 7 auction of Maps & Atlases, Natural History & Color Plate Books is a vignette that at first glance seems more charming than important — until you know the true story of The Original Beaver Map.

Beaver Map Iterations

Lot 54: Nicolas de Fer, L’Amerique Divisee Selon Letendue de ses Principales Parties, engraved decorative wall map, Paris, 1713.

Sold June 7, 2018 for $30,000.

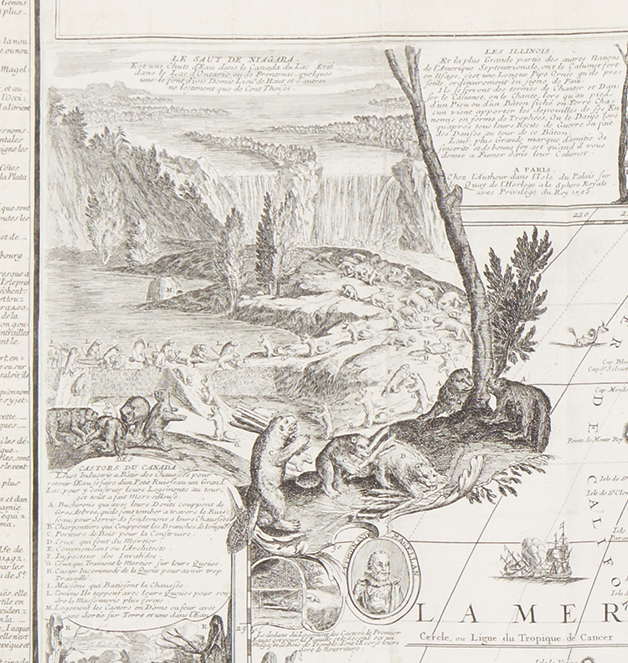

Nicolas de Fer’s L’Amerique Divisee Selon Letendue de ses Principales Parties, 1713, was more of a lure for adventurous fortune-seekers than it was tool for navigation. Encircling his map of North and South America are several small engraved scenes boasting the sights to see and riches to gain on the continents. Here, for the first time, is included a vista of Niagara Falls, the foreground of which is crawling with dozens of strangely humanoid beavers engaged in a variety of tasks that bear little resemblance to the actual activities of the creature.

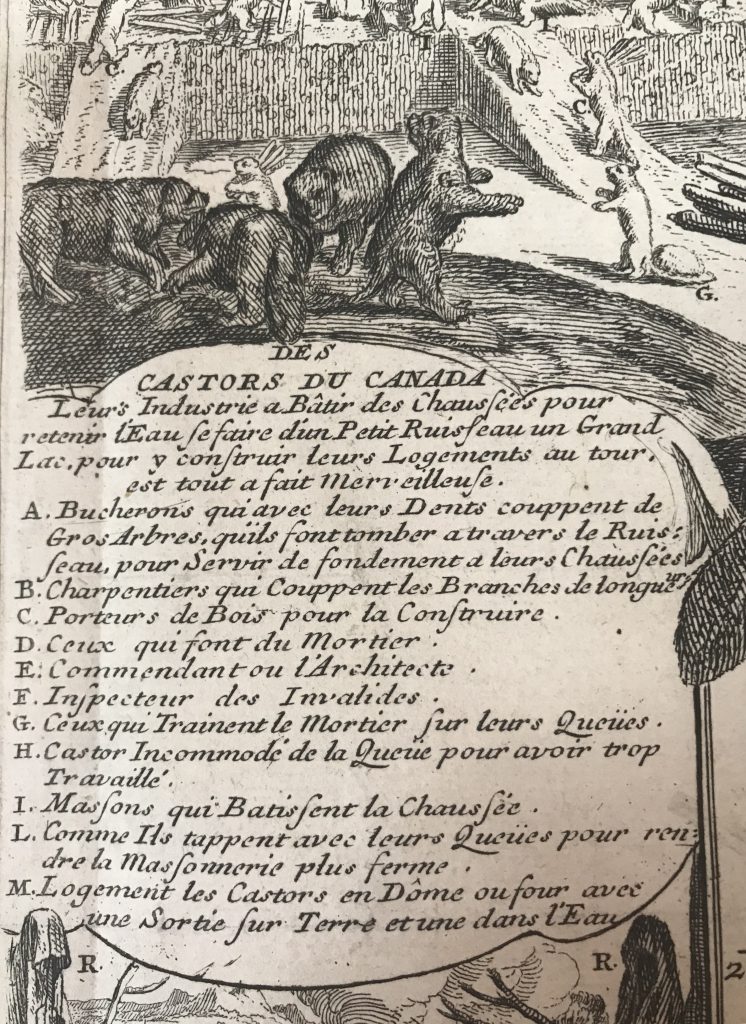

A close-up view of the beaver cartouche on Nicolas de Fer‘s map.

Why? The answer is manifold, and helps to explain the vignette’s enduring popularity for centuries following. By the eighteenth century, the Eurasian beaver was nearly extinct after centuries of dogged hunting in order to obtain their valuable castor oil and pelts. Thus the vision of a multitude of beavers was not only a novelty to western Europeans, but a recognizable promise of apparently instant and endless wealth.

Meanwhile, as industry in Europe became more regulated, groups of people worked in tandem to complete a single large task. According to the Osher Map Library, the actions of the beavers “mimicked the carefully regulated division of labor that was by 1700 increasingly common in the construction of major public works.” The fantasy of the beavers’ teamwork against the splendid background of the falls suggested to the potential explorer that if critters could realize monumental infrastructure in the New World, a human community could achieve even more. De Fer’s beavers are supplemented by a key, in French, of the various tasks that employed the beavers en masse.

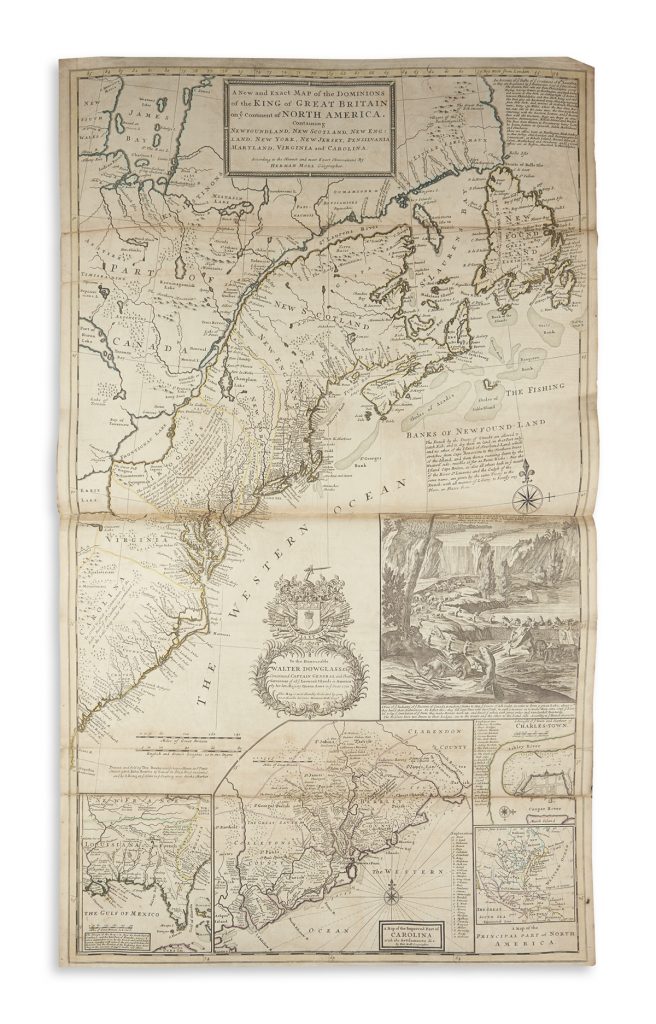

Lot 273: Herman Moll, The World Described, with 30 multi-sheet folding maps, including “The Beaver Map,” London, circa 1735 or after. Sold June 7, 2018 for $22,500.

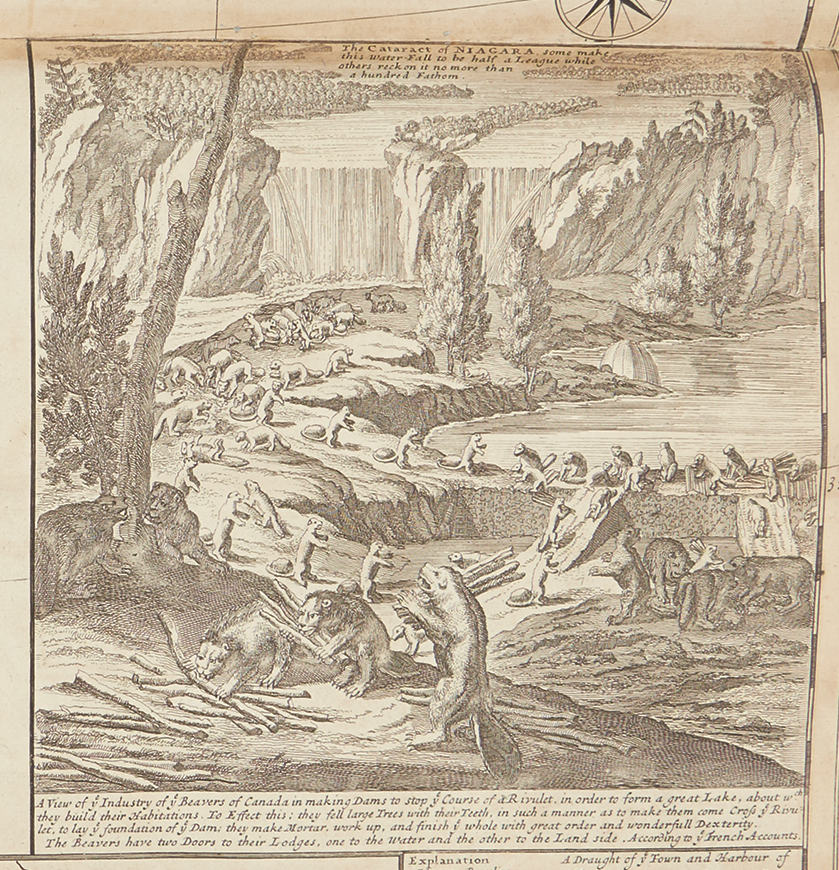

However, the beavers did not end here. Their most famous appearance was by Herman Moll in his circa 1735 atlas, The World Described, which became known as “The Beaver Map.” The cartouche was the only decorative element on the spread showing the East Coast. Perhaps because it was housed within an atlas, this map survives in greater numbers than de Fer’s and is therefore better known to collectors. Moll’s version is the mirror image of de Fer’s due to the fact that the engraver copied it directly from the original. The letters denoting various activities, however, have been left out.

A close-up of the beavers in Herman Moll‘s atlas.

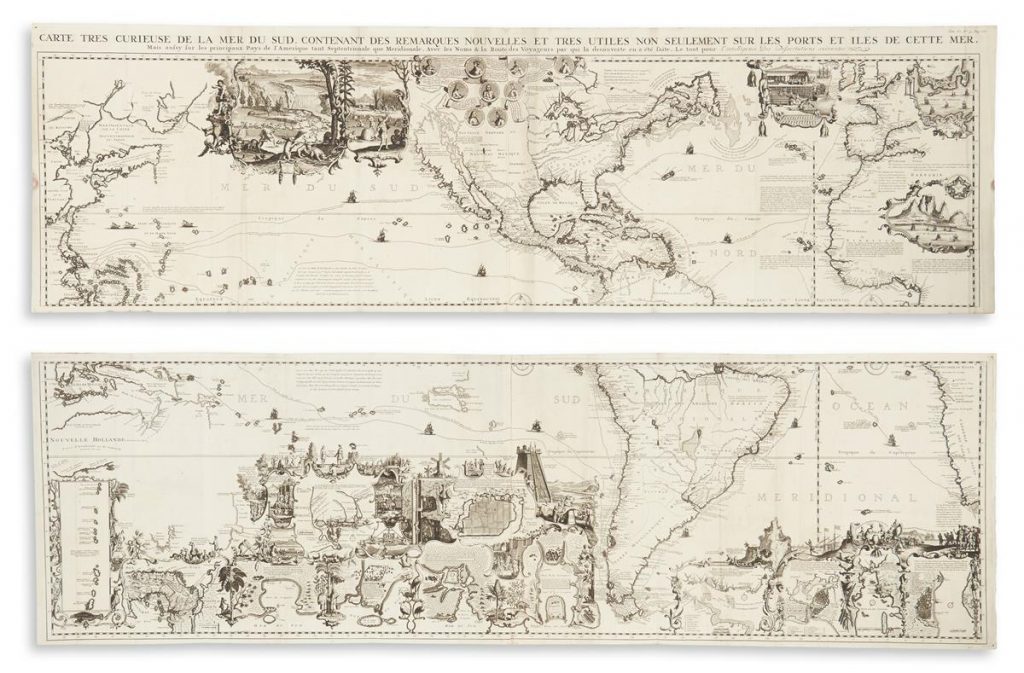

Another iteration of de Fer’s beavers appeared on a 1718 map by Henri Abraham Châtelain: Carte Tres Curieuse de la Mer du Sud, Contenant des Remarques Nouvelles et Tres Utiles non Seulement sur les Ports et Iles de Cette Mer. This map, incredibly, is sometimes called “The Dutch Beaver Derivative.”

Lot 38: Henri Chatelain, Carte Tres Curieuse de la Mer du Sud, Contenant des Remarques Nouvelles et Tres Utiles non Seulement sur les Ports et Iles de Cette Mer, “The Dutch Beaver Derivative,” Amsterdam, 1719. Sold June 7, 2018 for $9,375

Close-up of the cartouche on “The Dutch Beaver Derivative.”

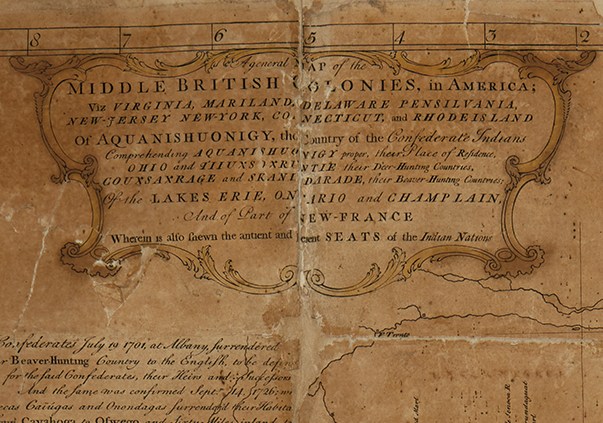

The French quest for beavers was a driving force in the north- and westward expansion into the continent. In addition to their inherent value, colonists and explorers loved the beavers for their relatable industriousness. They were such an important resource in nascent New York that in the 1630s, a proposed seal for the colony featured two leggy beavers.

A circa 1630 proposed seal for New York. Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

What Beavers Do and Do Not Do

While they may have valued the beavers, the explorers were largely wrong about just about everything regarding the creature. They do not, for example, look like a small, hairless bear. They look like this:

The American Beaver. Courtesy of Popular Science.

So confounded by the beaver were Europeans that the rodent was classified as a fish by the church. According to Thomas Jefferys in The Natural and Civil History of the French Dominions in North and South America, 1760, “In respect of his [the beaver’s] tail, he is a perfect fish, and has been judicially declared such by the College of Physicians at Paris, and the faculty of divinity have, in consequence of this declaration, pronounced it lawful to be eaten on days of fasting.”

Responsibilities of the beaver, according to Nicolas de Fer.

The list of tasks performed by the beavers on The Original Beaver Map reveals a significant misunderstanding of their behavior. Here it is, translated by Professor Nancy Erickson of the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Research at the University of Southern Maine:

Concerning the Beavers of Canada: Their industry in building dams to retain water in order to turn a little stream into a big lake, in which to construct their lodges, is totally wonderful.

A. Lumberjacks who cut Big Trees with their Teeth, which they fell across the stream to serve as the foundation for their dams

B. Carpenters who cut the long branches

C. Bearers of wood for construction

D. Those who make the mortar

E. Commandant or architect

F. Inspector of the disabled

G. Those who drag the mortar on their tails

H. Beaver with a disabled tail from having worked too hard

I. Masons who build the dam

L. Those who tap with their tails to make the masonry firmer

M. Beaver lodge in the form of a dome or kiln with an exit on land and another in the water

Swann Galleries specializes in works on paper, not biology. However, we can say with certainty that these attributes are no longer recognized as accurate by the scientific community at large.

Relationship of Beavers to Maps

From a philosophical standpoint, one of the most interesting possible reasons for the endurance of the beaver maps is the very nature of beavers and of maps. Of all creatures, aside from human beings, one could argue that beavers are the greatest living influencers of geography. Their dams and lodges dramatically change the course of rivers and create lakes where once lay valleys. Their architecture fundamentally changes the land, the study of which is the exact purpose of a map.

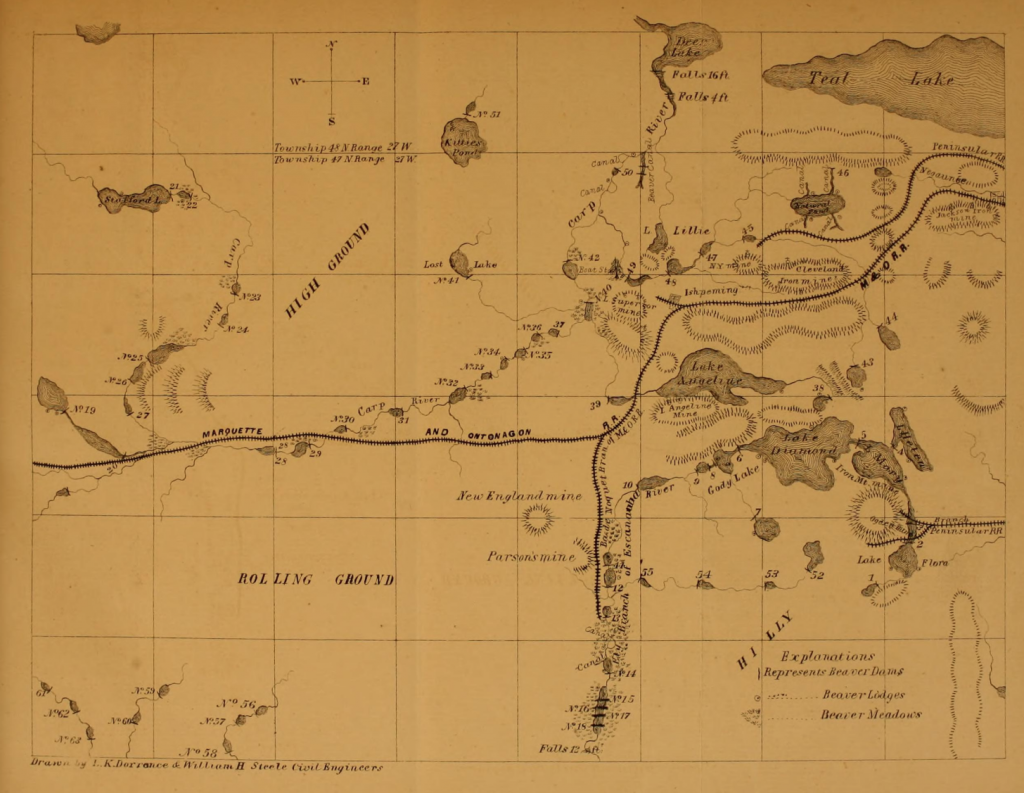

In 1868, the anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan published The American Beaver and His Works, a 396-page treatise on the life and times of Castor canadensis. According to Science Magazine, “Folded into each copy was a map, carefully drawn by [Morgan’s] railroad’s engineers, which detailed the locations of 64 beaver dams and ponds spread over some 125 square kilometers.”

Map from Lewis Henry Morgan’s The American Beaver and His Works, 1868, showing locations of beaver structures.

An article by Carol A. Johnston published in the August 15, 2016 issue of Wetlands, the official scholarly journal of the Society of Wetland Scientists, undertook to compare the data on Morgan’s nineteenth-century map with the current state of the same locations. The results proved the enduring effect of beavers on the landscape: nearly 75% of the structures on Morgan’s map were “still discernible in 2014.”

Indeed, a 2012 report by Charles D. James and Richard B. Lanman for the Bureau of Indian Affairs Northwest Region discovered that individual dams in the Sierra Nevadas had been “periodically inhabited for over a millennium until ~1850.”

Morgan himself suspected the longevity of the structures: “The great age of the larger dams is shown by their size, by the amount of solid materials they contain, and by the destruction of the primitive forest within the area of the ponds…. The evidence from these, and other sources, tends to show that these dams have existed in the same places for hundreds and thousands of years.”

Browse the full catalogue.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=OlBShB8qEWAQ7kNvwHbrXqd&_nc_oc=Adn09Fh3YL-11OkpQcrYGgFN9beLpm0IfGUn2bwN7iJs6d4v8qMeP8kSYmCw82y2ewU&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=I48jsxJwo9ZoAWYn9au3wg&oh=00_AfHBUMgxSwlbGJ-J9grZV8YWn6QTPcWAhOxtdTR-YDtzCA&oe=68199551)