Collectors on Collecting: Jules Feiffer on the Artists and Works from His Collection

Jules Feiffer’s career spans decades, producing a remarkable range of projects and generating numerous awards and honors. His contributions to the field of comics since his start in the late 1940s have been recognized with his induction into the Comic Book Hall of Fame and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writers Guild of America. His satirical strip, Feiffer, which explored contemporary politics and social issues, ran for 42 years and earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1986. He produced scripts for plays and films, including Robert Altman’s Popeye (1980), and won the 1961 Academy Award for the animated short Munro, directed by Gene Deitch. Yet it was the artistic brilliance of Will Eisner’s comic strip The Spirit that shaped his path as an illustrator and author and gave him his start.

At the age of 16, Feiffer worked as an assistant to Eisner on The Spirit, contributing to the groundbreaking newspaper strip that revolutionized the comics medium. Feiffer’s admiration for artists like Eisner spurred his development as a writer and cartoonist, leading to his distinctive gestural inking style. By the time he was offered a comic strip in The Village Voice in 1956, Feiffer was well-positioned to become a prominent voice in the emerging counterculture of the late 1950s and early ’60s. Through it all, Feiffer’s admiration grew for artists such as David Levine, Ed Sorel, and Milton Caniff, fueling his passion for collecting their work and leading to many personal relationships. Today, Feiffer inspires a new generation of artists who revere him as he did his own heroes. This collection, amassed by Feiffer, records his enduring enthusiasm for comic art and his lasting friendships.

Below, Feiffer shares in his own words his memories of working with his fellow artists.

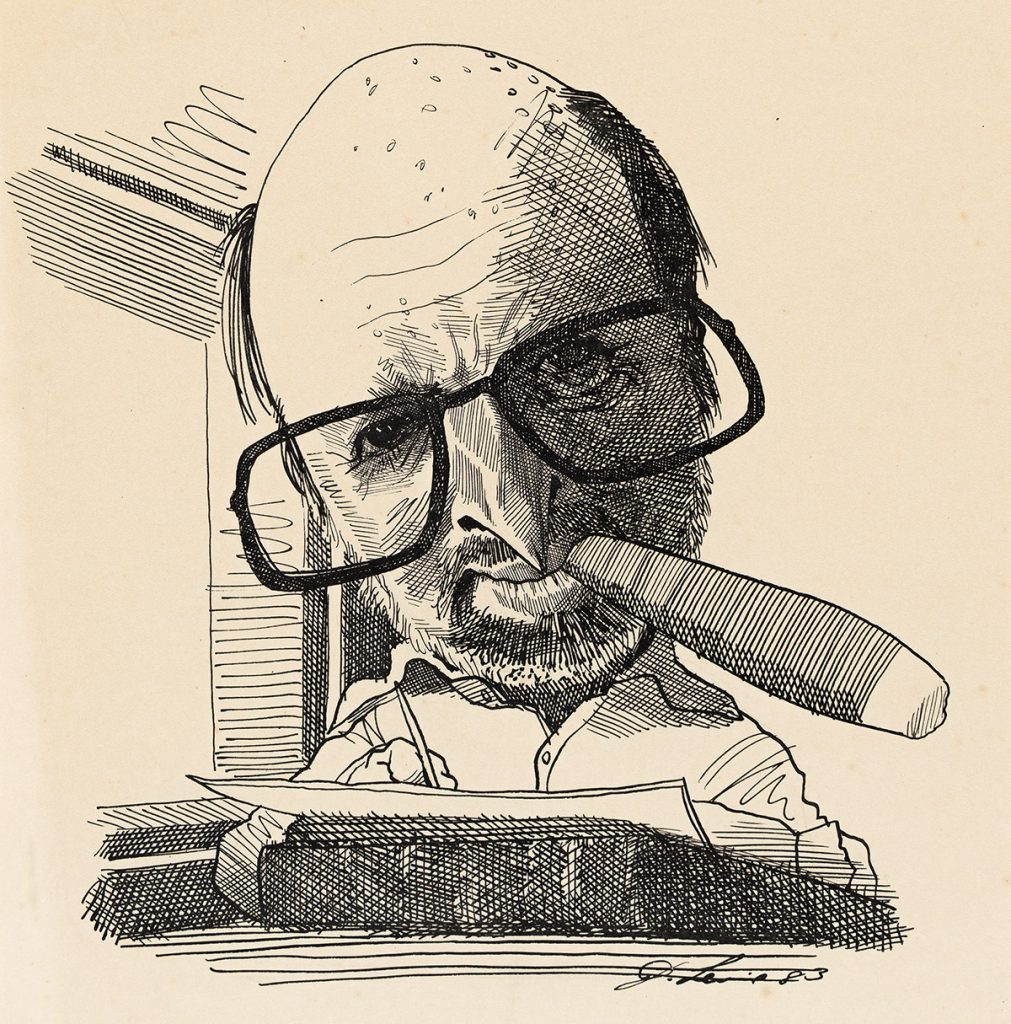

David Levine (1926-2009)

“In the second half of the 20th century, David Levine was the most important literary and political caricaturist. When he began, there was very little political caricature and very little literary caricature. He revived the art. When I was in the army. I met a Brooklyn painter, Harvey Dinnerstein, who was stationed with me, and we became close friends. He was part of a gang of Brooklyn painters, which included David. All of these guys were serious painters, but David was the only one among them who was a cartoonist and a cartoon fan. The first thing David wanted to talk to me about was whether I knew a comic strip by a man named Sheldon Mayer called ‘Scribbly the Boy Cartoonist.’ I was a huge fan of his, and when David brought him up, we started talking about Scribbly, and that was the connection that we both made with each other, and we became lifelong friends.

“In 1963, Bob Silvers had asked me to be the New York Review of Books staff artist but I could not be involved with them because I was not going to leave the Village Voice. But did they know the work of David Levine? David had these spot drawings in Esquire at the time, along with his oil paintings and watercolors. David started from almost the first issue of the New York Review of Books and became the visual signature of it so that you could not look at that paper without thinking of David. He understood, in a way I never could do in a single drawing, how to make a socio-political, literary point, and that would be the only way you could ever look at that person after that.

“I don’t think this work has ever been published. It was a birthday gift to me.”

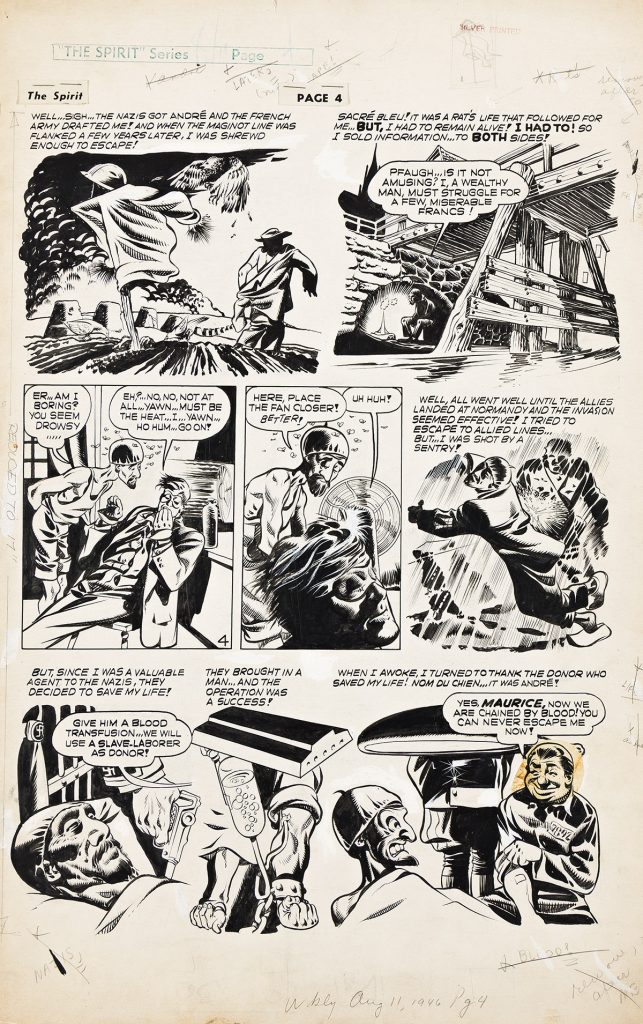

Will Eisner

“Will Eisner is a national treasure. His comic, The Spirit, is like no other. It looked like a storyboard for a new Orson Welles movie: high contrast, multi-angled, expressionist panels overpowering with atmosphere. I fell in love.

“For a few years, before I went into the army, I was the ghostwriter on The Spirit. Not every week, but most of the time. I would write out of The Spirit story, or my idea of one, and lay it out, and then Will would go over it and put his changes and that became that week’s Spirit section. And I wasn’t even 21! I loved working for him!

“You look at this work, and it just stops traffic. Nobody was like Will, and nobody did anything like this. It’s beautiful, and it’s art, without a doubt. I may have worked on this page as his assistant. The comic book page, before Eisner had reduced itself to six or fewer panels and wasn’t jammed with information. Eisner, in The Spirit, brought the Bronx back into comics. He just jammed everything into one page and somehow made it storytelling and understandable and atmospheric. Comic book pages at the time would be six panels at most, and this is 11 panels. That was unheard of. Eisner was the only one to do that. My assumption is that in seven or eight pages of “The Spirit” section, he had so much story to tell that he had to cram it all in. I look at the page, I see the atmosphere created by a fellow Bronx boy. It may be called Central City, but that’s the Bronx, as I grew up in it.”

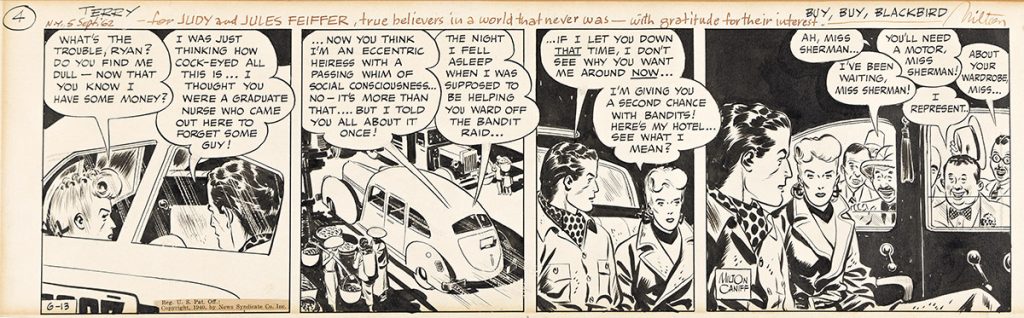

Milton Caniff (1907-1988)

“Before Eisner and along with Eisner, Milton Caniff was my hero. Terry in the Pirates was my idea of what a comic strip should be. It was like a movie on paper. He was the first guy to use heavy shading and that realistic look, and he was a good writer. He could tell a story and get you involved with the characters. Caniff, who I later became friends with, wrote for grown-ups. You believe in the relationships and identify with the characters as if they are real people. Real people meaning actors in a good movie. Not real life. Because it is so clearly romance.

“The dialog, which there is more of than in most scripts, is sophisticated and adult and well-written. The layout is movie layout — in that it moves from panel to panel like a screenplay. Milt was the first cartoonist to put all this together on a comics page. No one did it before him. He fashioned adult material for a daily strip in the comics and for a Sunday page in color and it worked more successfully and on a higher level than in any other comic strip of his time.”

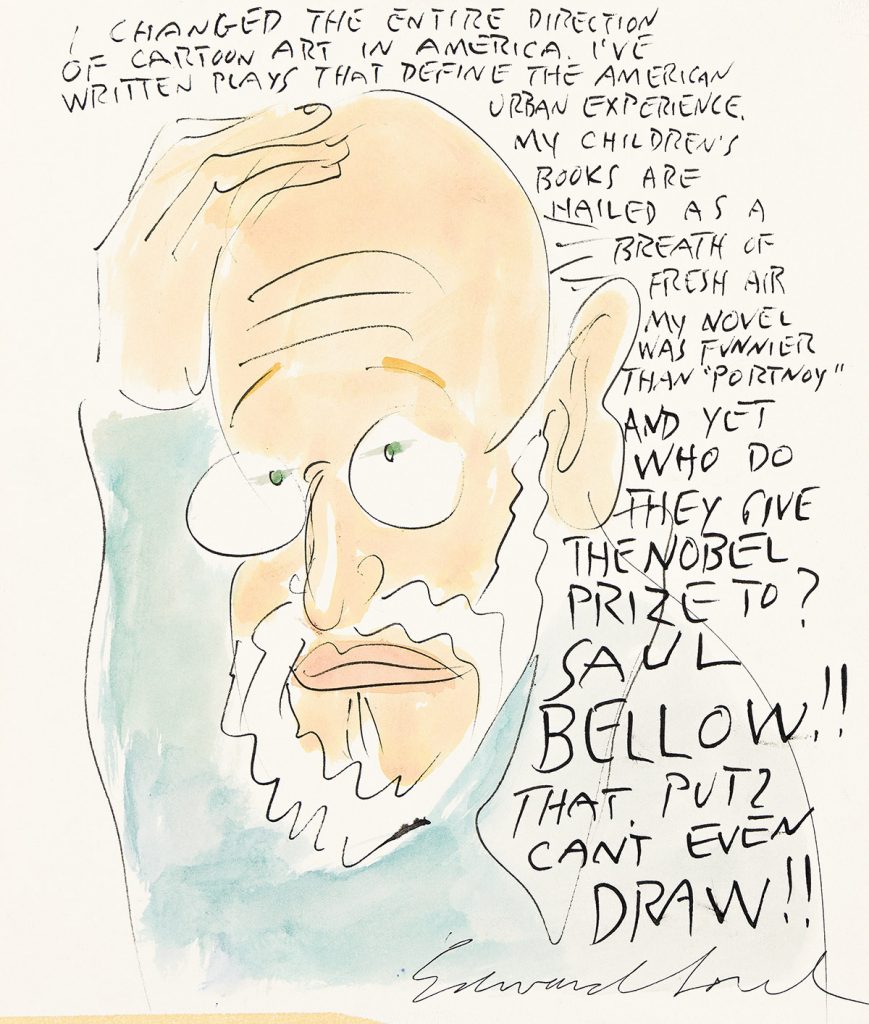

Edward Sorel (1929-)

“Ed Sorel has so many different styles and was always working toward another. I love this particular style. I’m sorry he gave it up. Sorel, Levine, and I saw ourselves as a kind of a lefty radical threesome in the cartoon commentary world. I met Ed when I was starting out; I think even before I was in the Voice, I came across The Push Pin Almanac that Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast and others were putting out. It was all a device to distribute their work and get work. To get assignments before they were commercially viable—it worked. I went up to see the guys because I thought maybe I could be part of that group, but Glaser, who was the boss there, didn’t think much of me.”

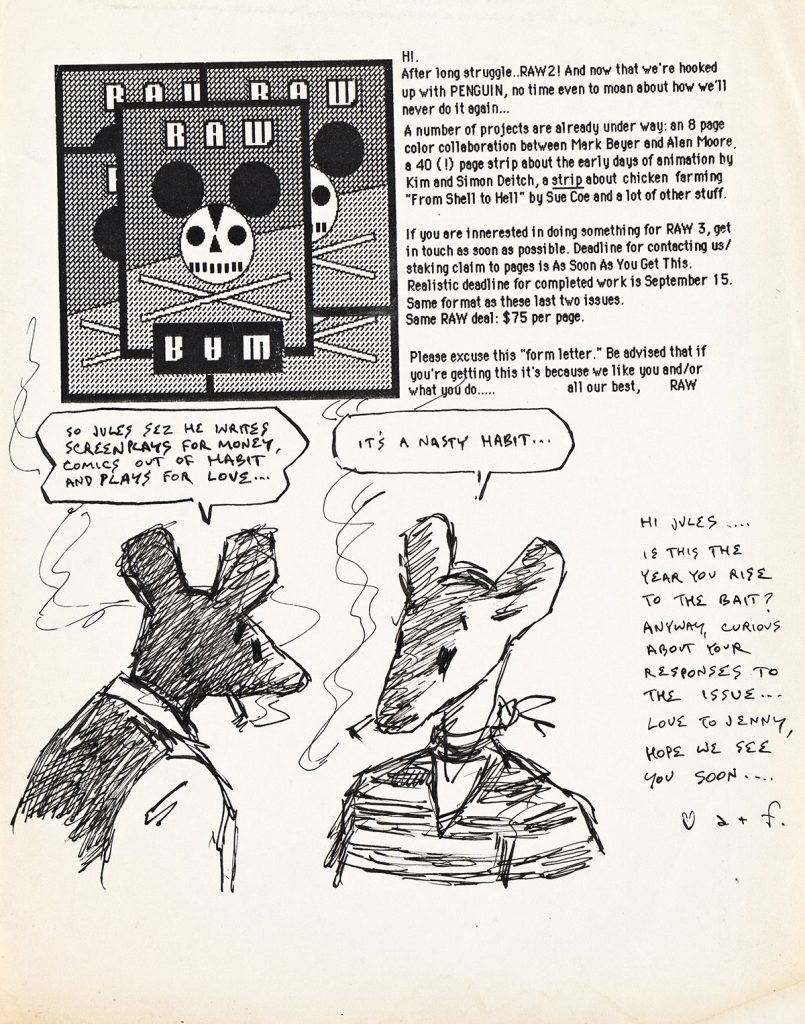

Art Spiegelman (1948-)

“What is there to say about Art Spiegelman? He changed the cartoon world, that’s all. He is generous, open, interesting. The only thing I have against him is he should have been doing more books over the years. He’s a genius. Other than being an artist and writer, as an editor and a kind of elder statesman of the present-day-serious cartoon world, he has done invaluable work in Raw. He and his wife, Françoise, together. He’s a public figure in the cartoon world. One of the few. It’s not about his work. It’s about the profession that he’s involved in and what he can do to further it, change it, and goose it. He’s both a great cartoonist and a great cartoon fan.”

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=m-4Ir9scQRgQ7kNvwF0EC_d&_nc_oc=Adk6vWHvJMH5TK67zw75jTpjO3KqV6u2qJzpfUwC4bmSaYLGiSmw5xfkUuplusJ5mI8&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=4U4CHLYdu78WkdUqz4Xo1w&oh=00_AfG9ug13M8ekS4Det61ZgnIqaeZrxFz_1gIX22cE4pAG-w&oe=6809C351)