Letters from Us: Epistolary Novels by Women

From Aphra Behn’s Love Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister, 1684, to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, 1823, and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, 1983, the epistolary approach to novel-writing has been employed repeatedly by generations of women. Constrained by social norms that suppressed and controlled women’s self-expression, the domain of private written correspondence has represented a safe haven for the airing of unconventional (and often feminist) views for centuries.

For many a budding author in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the format presented a perfect entrée into the novelistic form. Letter-writing and reading would represent a substantial part of any literate woman’s daily activities. As an intimate form of communication familiar to women, and not subject to the judgment and scrutiny of others, it seems a perfect fit. What is the narrative of life itself, but a story built up by a series of letters exchanged among a group of characters?

As a result of the feminine interest in writing and reading such work, it exists in a liminal space: popular, but not valued. Women’s creative outputs were necessarily devalued by the culture at large, excluded from the canon, and considered unworthy of scholarly notice. In the world of early and rare books, the echo of this marginalization rings out. In the book trade, collectors have been sparse, and values have stayed low. Libraries have not prioritized purchases of women’s contributions to literature and institutional holdings show obvious gaps.

It is a privilege to shine a light on some of these forgotten authors. In this year’s Focus on Women sale, we are pleased to offer several interesting epistolary novels written by women.

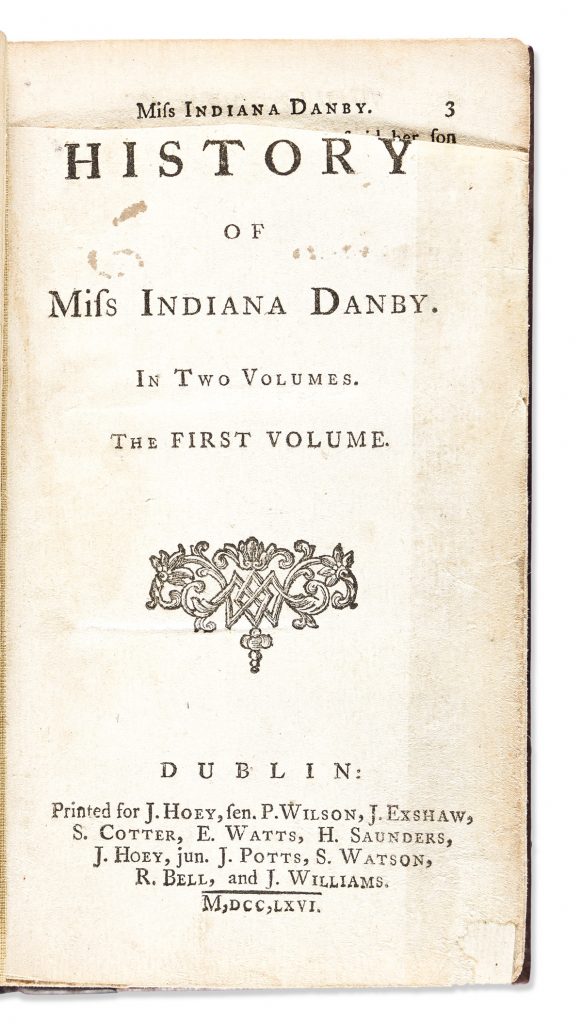

Lot 4 is an anonymous work attributed to “A Lady,” and reports the adventures of the fictional Miss Indiana Danby (sometime before Mr. Jones was invented), and was produced to appeal to women with entertainment deemed appropriate for their expected interests and tastes. Although somewhat formulaic in its plot and novelistic devices, similar stories published in this period nonetheless informed heavily the work of young and emerging female authors. Published ten years before Jane Austen’s birth, Miss Indiana Danby’s adventures can be read as a set of steps from the ground floor of women’s writing, leading hopefully up into higher and more sophisticated levels of storytelling.

This work, published in Dublin in 1766-67, is so rare, it seems unobtainable. The mystery of the author’s identity also seems worthy of study.

Lot 4: The History of Miss Indiana Danby, four 12-month volumes bound in two, Dublin, 1766-67. Estimate $2,000 to $2,500.

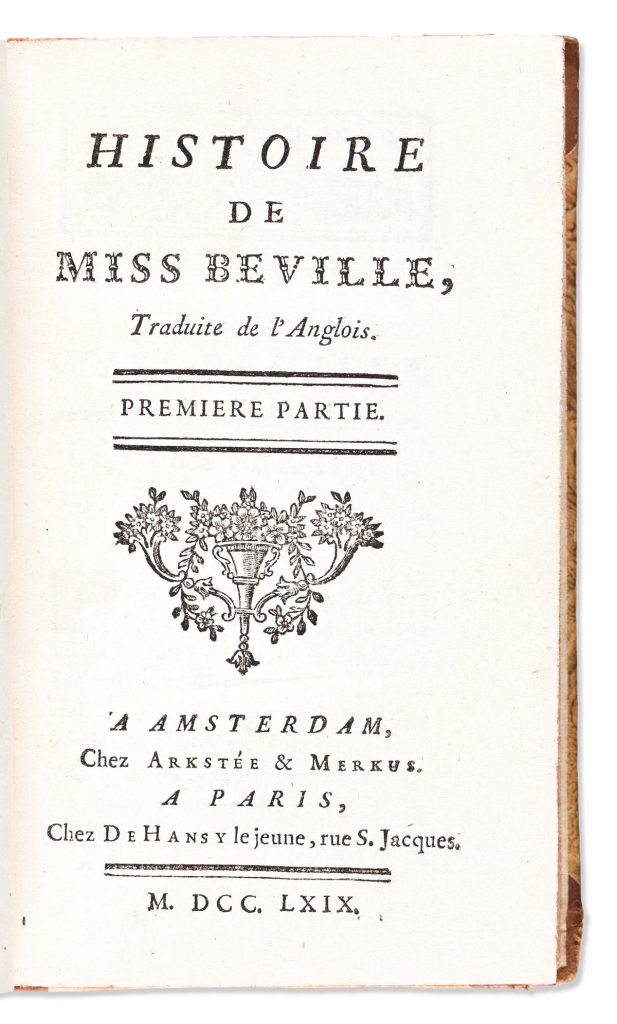

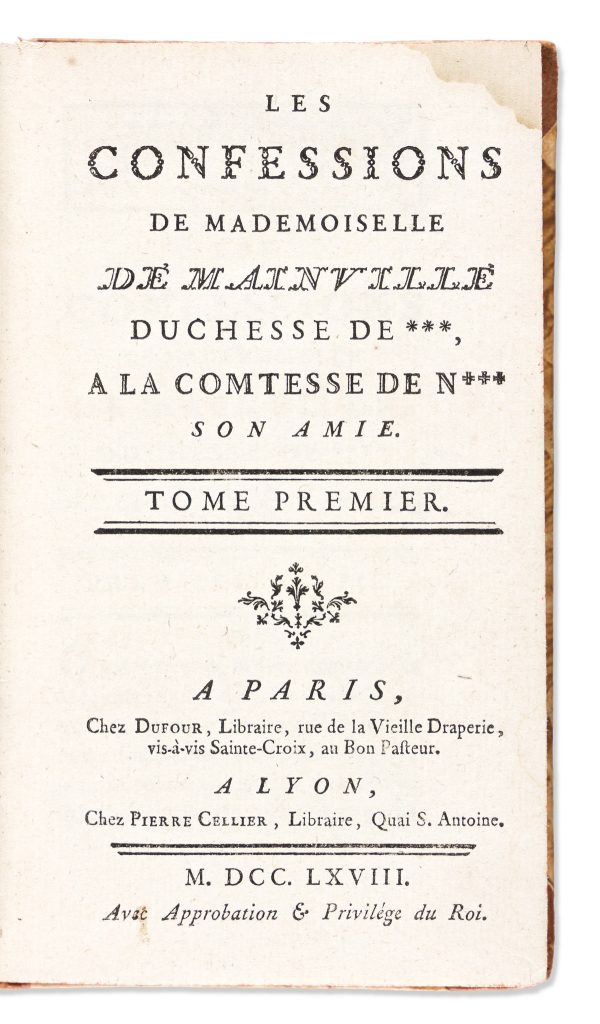

Lot 139 is a finely bound set of six volumes from the late 1760s that includes three separate novels translated from English into French. Histoire de Miss Belville, sometimes attributed to Charlotte Palmer, first appeared in London in 1780 under the title Female Stability: or, the History of Miss Belville. In it, the author weaves multiple plots of love, dishonor, and intrigue. The 1769 French edition offered in this lot is seemingly unrecorded, with no copies listed in any library worldwide.

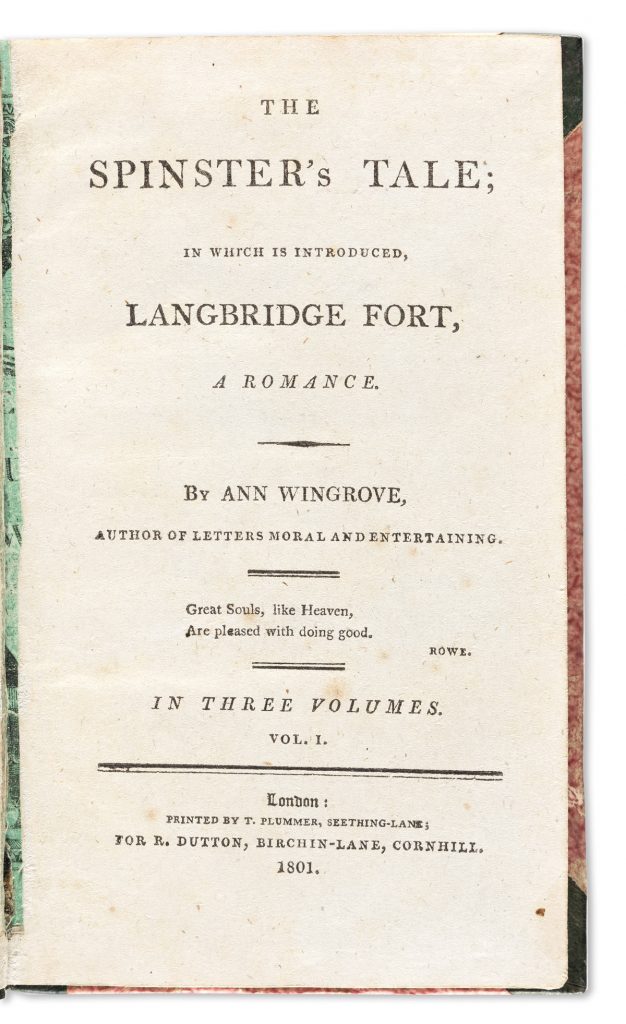

The same is true of lot 186, Ann Wingrove’s The Spinster’s Tale, 1801. This beautifully preserved three-volume set is listed in the collection of one library worldwide. Its author thanks her role model, the author Jane Iliffe West, known by her pen name, Prudentia Homespun, at the start of the first chapter: “Being a great admirer of the writings of my sister authoress, Prudentia Homespun, I have adopted her title, and though my tale may be inferior to that lady’s yet I think we are actuated by the same animating principle; for if we can persuade one reader to avoid or quit the paths of vice, or confirm another in the practice of virtue, we have not been useless members of society.”

West’s A Gossip’s Story served as Jane Austen’s source for Sense and Sensibility, a reminder that we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Lot 186: Ann Wingrove, The Spinster’s Tale; in which is Introduced, Langbridge Fort, a Romance, first edition, three volumes, London, 1801. Estimate $1,000 to $1,500.

Beyond the Epistolary Novel

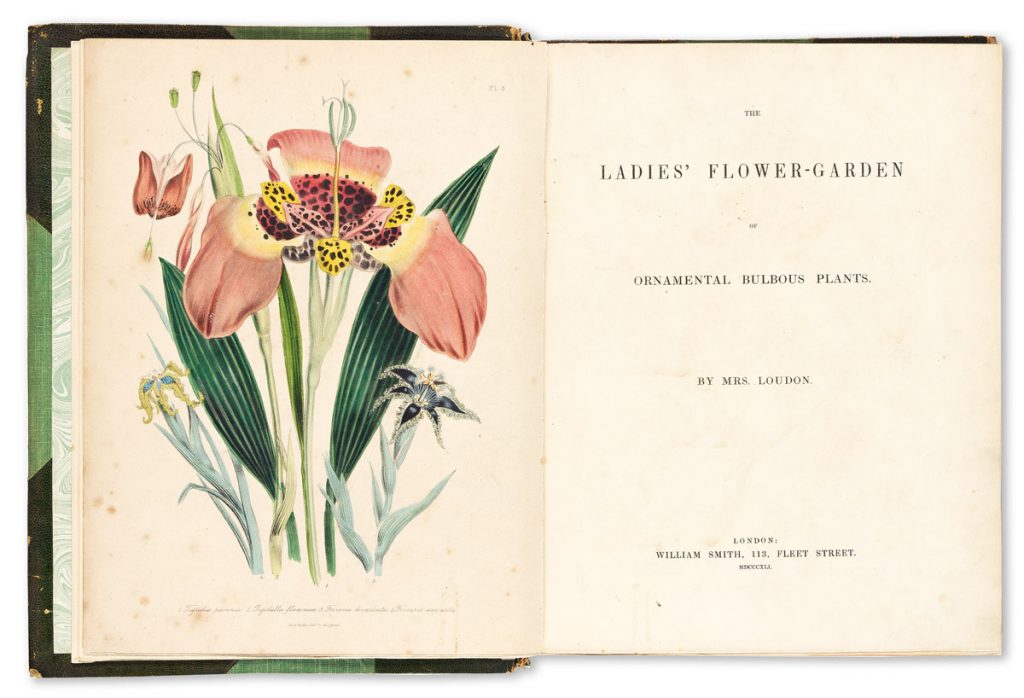

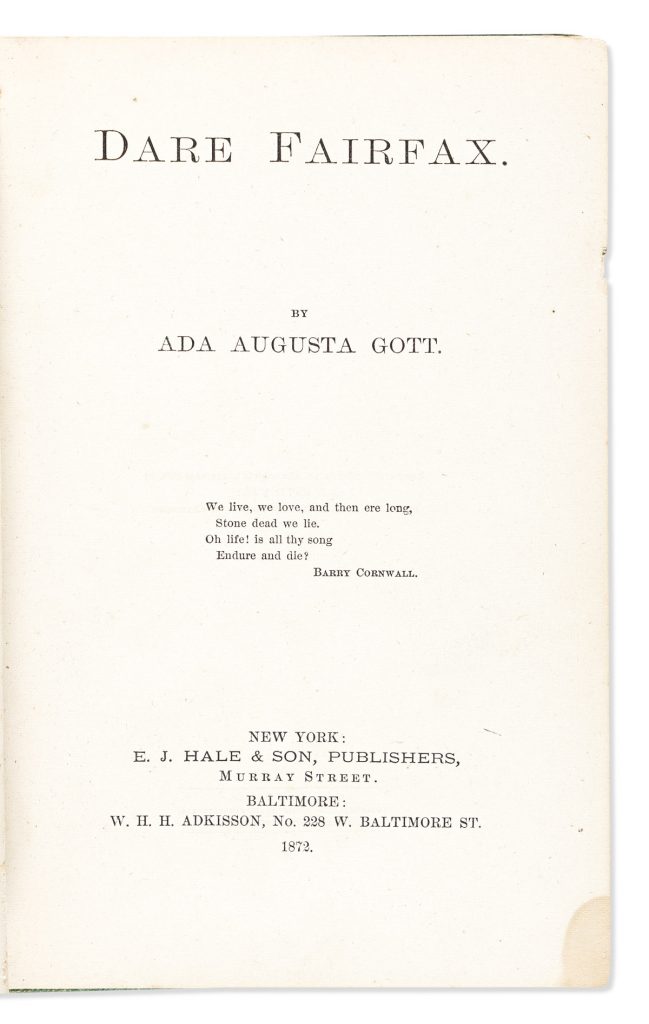

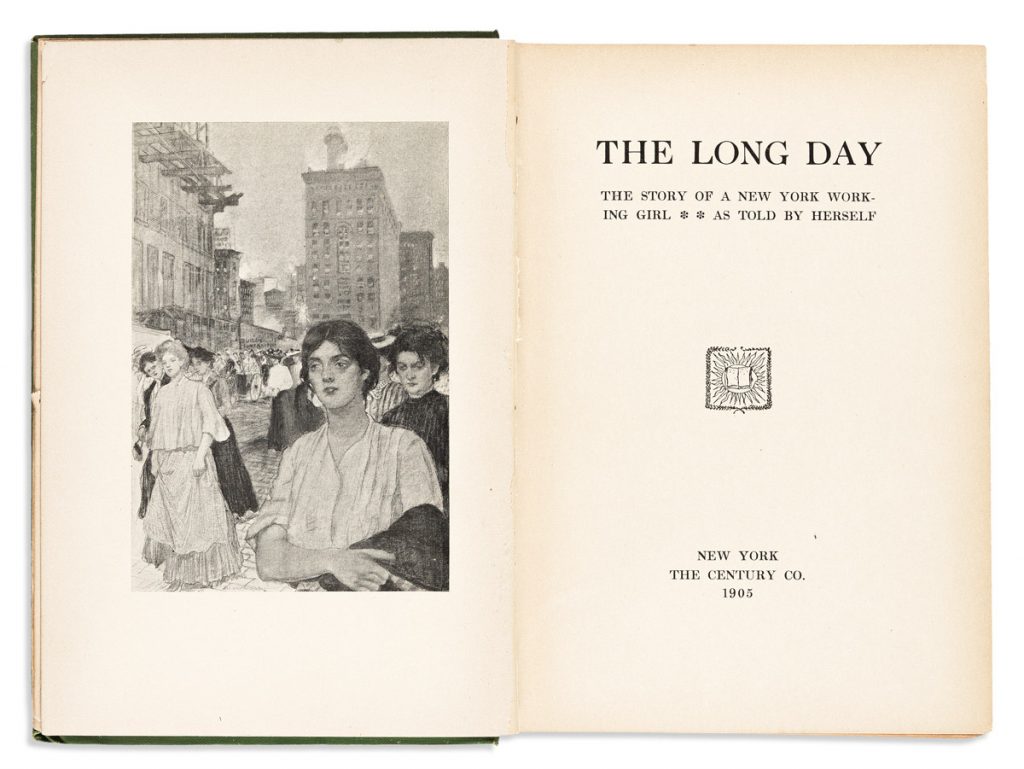

From left to Right: Graphic Novels by Helena Bochoráková-Dittrichová: Lot 10: Enface, first edition in French, Vyškov, 1930. Estimate $300 to $500. And, Lot 13: Z Mého Deství Drevoryty, first edition, Prague, 1929. Estimate $4,000 to $6,000; Lot 119: Jane Wells Webb Loudon, The Ladies’ Flower Garden of: Ornamental Bulbous Plants [and] Ornamental Perennials, first edition of Bulbous Plants, second edition of Ornamental Perennials, London, 1841, 1849. Estimate $1,500 to $2,000; Lot 65: Ada Augusta Gott, Dare Fairfax, first edition, New York, 1872. Estimate $250 to $350; Lot 190: The Long Day, 1905, by Dorothy Richardson, part of three early 20th century novels. Estimate $200-300.

Helena Bochoráková-Dittrichová’s autobiography is the first graphic novel published by a woman.

Jane Wells Webb Loudon successfully promoted the idea that gardening was an appropriate hobby for young women through the publication of a number of books in the present series. She also wrote a science fiction novel before the genre was known by that name. In 1827, at the age of seventeen, she anonymously published The Mummy!, in three volumes, which she describes as “a strange, wild novel” set in the twenty-second century.

Early twentieth-century novels related to women at work feature including Dorothy Richardson’s The Long Day, the Story of a New York Working Girl as Told by Herself, 1905. The Long Day tells the story of a working-class girl from a small town who moves to New York City. She works in a number of industries in the city, including fabricating boxes, making artificial flowers, sewing, and finally finds work as a typist. Working conditions are dire, and shifts are twelve hours a day. For this, our protagonist earns a few dollars a day.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=QlZg0o3Vx4oQ7kNvwHlPDYS&_nc_oc=Admkx5CH3-5gNl9kFtE07uGBWzC1TrU8LutoXTk30m77fiWC0m2_oIjIUSQBbJE8mA8&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=ug2FTJSZlk2bA7d_6u98Cw&oh=00_AfKuxS7GX73un26jqQ-rUbZIygtd1ST6-oNoEzMquVAkuQ&oe=68276D11)