Devon Eastland’s Specialist Picks: What to Watch in the October 12, 2023 Auction

Devon Eastland shares her picks for the October 12, 2023, sale of Early Printed books.

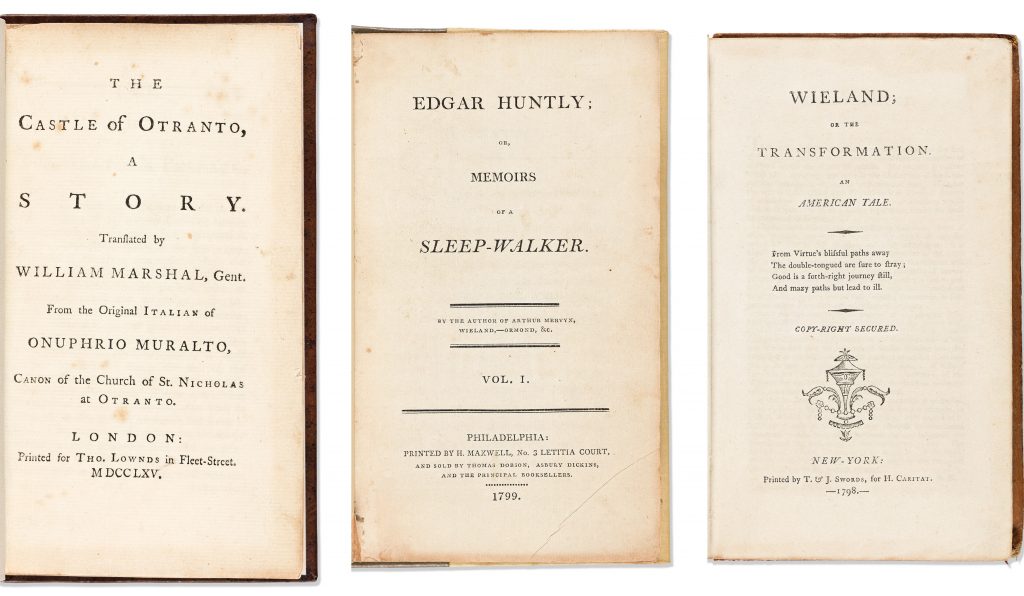

Gothic Novels

If you’ve read through our offerings for the October 12, 2023, sale, you know that the cataloguer loves gothic fiction. High spots in the sale include first editions Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, the first in the genre, and Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland, the first American contribution (not to mention Brockden Brown’s Edgar Huntly). If you listen to true crime podcasts and are pretty sure that eighteenth-century fiction is going to feel stilted and irrelevant, think again. Each story pulls from epic true crime and the authors aren’t shy about throwing in supernatural and psychological elements like sleepwalking, demonic possession, ventriloquism, and family annihilation. It’s all on the table. Get ready for the eighteenth century to feel modern.

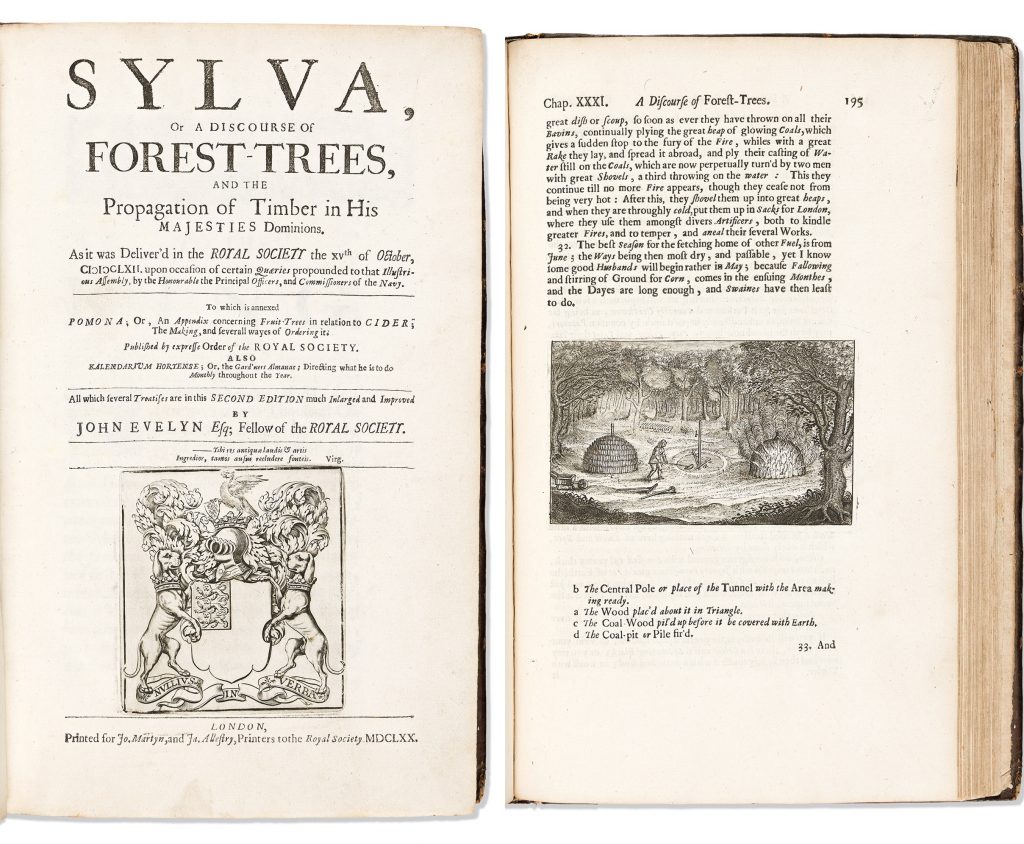

Forest Trees

We book lovers are not afraid to dig into the details, and one of my favorites has always been John Evelyn’s book on the woods and its leafy (and needled) denizens: Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees. Seventeenth-century Brits were bent on improving the land and maximizing the output of their gardens, forests, and streams, and Evelyn’s contribution is one of many venerated volumes from the period. Evelyn first taught me about coppicing (intentionally cutting down trees and shrubs to stimulate sucker growth thereby providing firewood), pollarding (pruning upper branches from trees to create fodder for livestock), the many forms of grafting (attaching the trunk and branches of one variety of tree shrub to a rootstock of another so that the desired fruit or flower has a hardier foundation), and creating espaliered fruit trees (specially pruned and shaped against garden walls for beauty and yield.) However, his description of the process of charcoal-making is the most interesting, in my opinion. Look it up, he even includes an illustration. (If looking it up isn’t for you, come to the exhibition and ask me about it.)

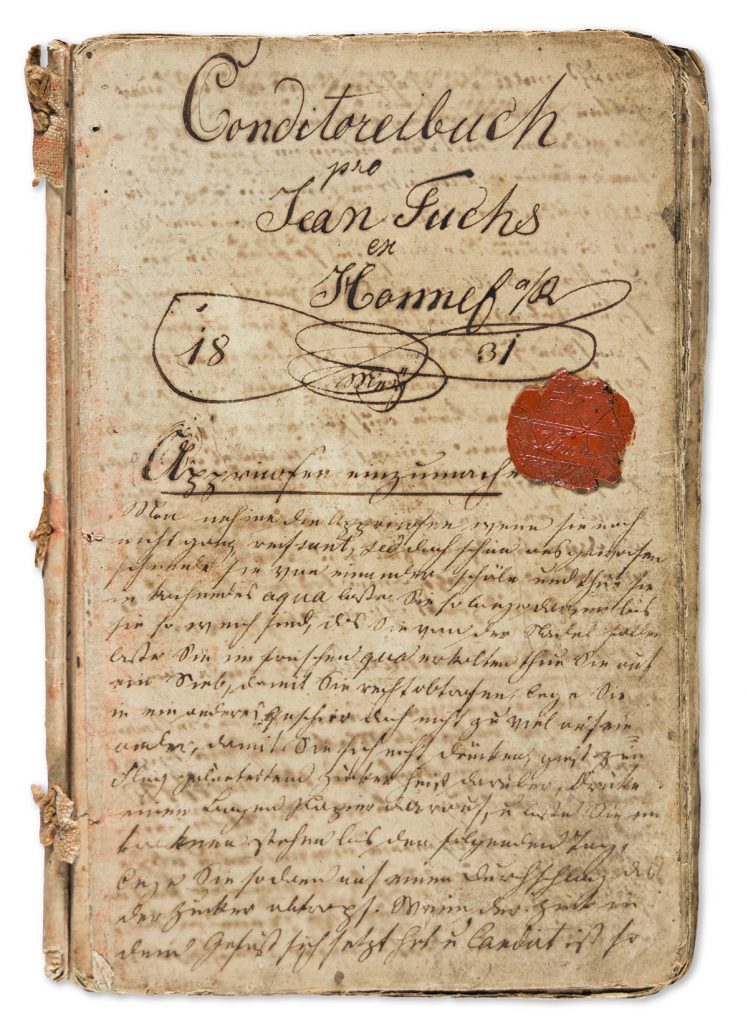

Traveling Pastry Chef

Lot 146: Jean Fuchs, Handwritten Pastry Recipe Book and Passport, Honnef, Germany, 1831. Estimate $600 to $800.

Manuscript material provides unparalleled access to the private lives of history’s forgotten people. Jean Fuchs flourished in the 1830s as a traveling pastry chef, but it seems that not much has survived of his personal history beyond the material in this lot. That may change, but that’s as much as we know at the moment. His recipes are written in the languages of Europe, and his passport tells us why. I’m not sure how much is known about itinerant workers in the food industry in early nineteenth-century Europe, but I know a treasure trove of raw information when I see it.

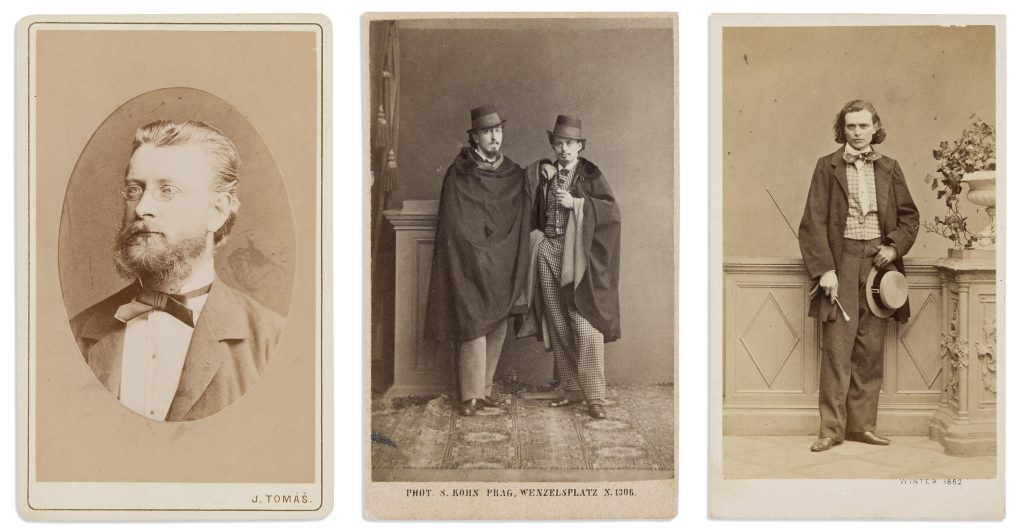

A Doctor’s Circle

Czech Republic-born Arnaldo Cantani was a physician from an Italian family who contributed to our understanding of the importance of diet for people living with diabetes, but nothing tells the personal story of his lifetime of networking better than this album of signed carte-de-visites. Cantani’s doctor friends from all over Europe exchanged formal portraits, many leaving a signature and sometimes a short note. Bundled together in a contemporary album, the group serves as a snapshot of a very specific mid-nineteenth-century European medical social circle.

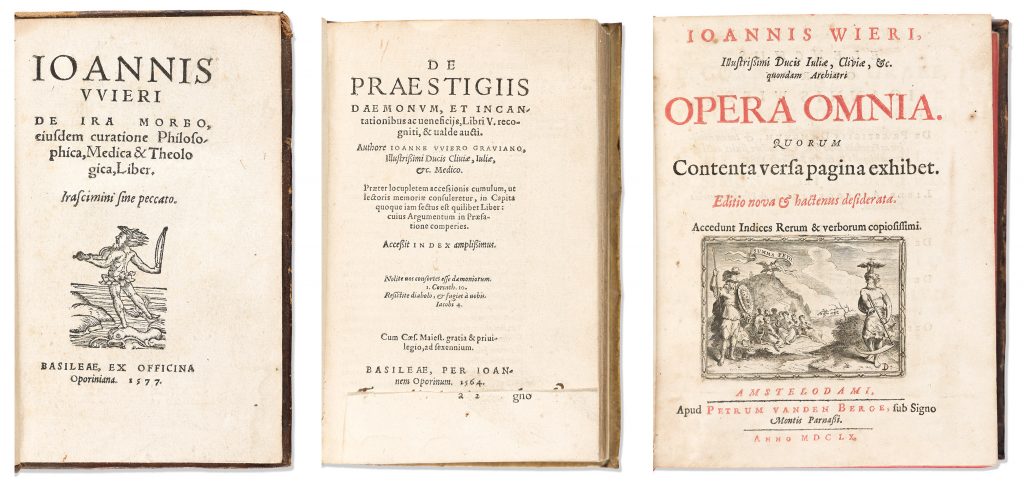

Science over Superstition

Inquisition-era folks are usually painted with a broad brush, as though everyone from the period believed in witchcraft and sorcery. Dutch physician Johann Weyer took a clear-eyed and rational approach. He practiced medicine and published widely, never backing away from his position that witchcraft simply did not exist. In a time when the doctrine of the church trumped the scientific method in many arenas, Weyer advocated for an understanding of aberrant or inappropriate behavior in a medical context. He suggested that an imbalance of the humors, or an underlying mental illness, were the cause of people’s disturbing or irrational actions, not the work of the devil.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=OlBShB8qEWAQ7kNvwHbrXqd&_nc_oc=Adn09Fh3YL-11OkpQcrYGgFN9beLpm0IfGUn2bwN7iJs6d4v8qMeP8kSYmCw82y2ewU&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=tAw7REYwZZLTJH2gYFDRIA&oh=00_AfFntE5BpdhgoGI95lZi2PLq4mMH4VrDzFOq34kH3ACHug&oe=681B8F91)