Introduction to Bookbinding: Folding & Sewing

As a bibliophile expands their collection, they gain a feel for auction house and bookseller’s catalogues, which often include terminology that may seem arcane. However, every character in a complex catalogue entry is used to describe the object being sold. For early printed books, some of the most essential things a specialist must note are the size of the book, its collation, and its condition. In order to understand how a book is described, some knowledge of bookbinding fundamentals is helpful. Here, Devon Eastland, our senior specialist for early printed books, dives into how a book is sewn.

The Art of Bookbinding

After working intimately with books for thirty years, I have become somewhat blind to my own knowledge of book and structure, or else the details have become invisible to me. I had the privilege to help out on Greta Gerwig’s production of Little Women, and the subsequent small flurry of media attention reminded me that to many people, bookbinding structures are mysterious. When answering a journalist’s questions, I would begin to explain what I thought were straightforward concepts, but their ensuing queries showed me that more and better details were in order. Here we’ll cover some basics of bookbinding structure with some historical notes.

More from Devon Eastland: Why do old books use F’s instead of S’s?

Folding & Sewing a Book

Folio, Quarto, Octavo & Beyond

Western books are constructed of groups of folded paper (or parchment) leaves. The folded sections are called quires, signatures, or gatherings. With books printed on paper, the entire sheet is printed at once, one side at a time, and then folded up to form the signature. A large sheet, printed and folded once in half, makes the largest format book, the folio. The same sheet can also be printed with four pages on each side, in quarters, to form a book half the size of the folio and square-shaped, known as the quarto. When the same sheet is printed with eight pages on each side, and then folded one more time, we have the octavo, half the size of the quarto, and narrower than it is tall. As the folding continues, the resulting books become smaller and smaller, all the way down to duodecimo (or 12mo), 16mo, and even 32mo format books.

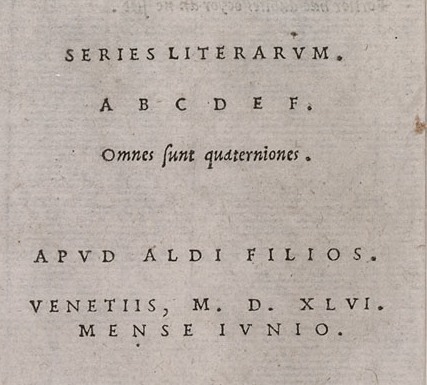

Translation: Series of Letters. / A B C D E F. / All are in fours.

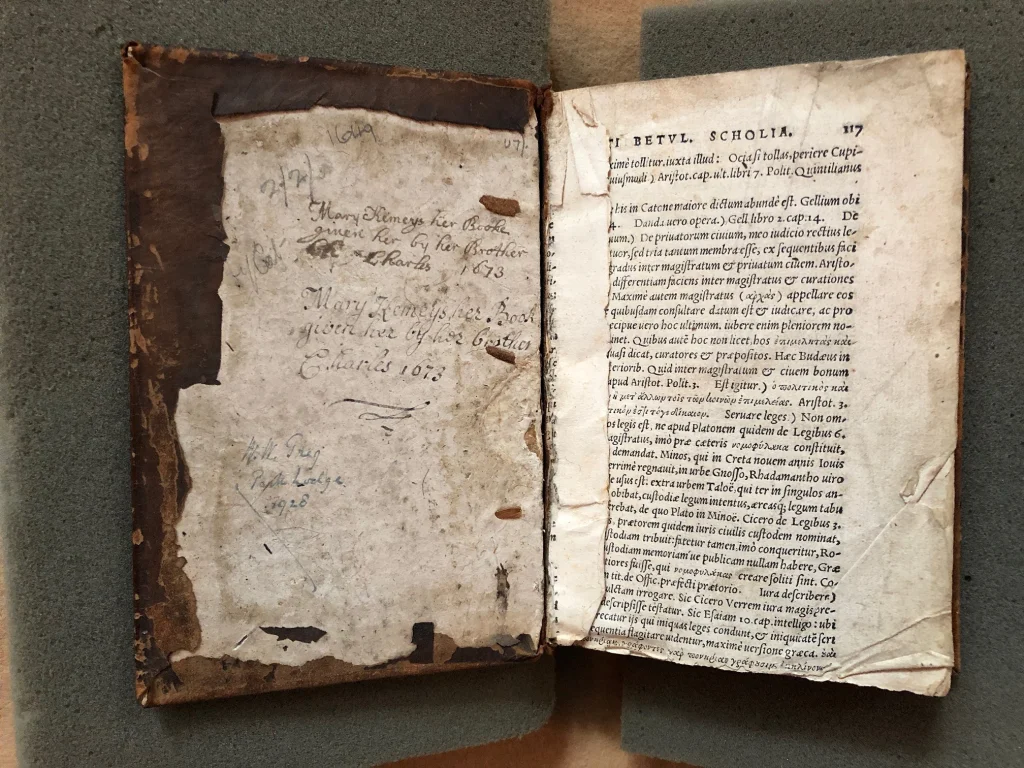

Once the printer has printed the book, the binder folds each sheet and arranges the signatures into their proper order. The printer letters each sheet in alphabetical order, to help the printer put the sections in the correct order, and to double-check that all signatures are present. Any illustrations printed on a different press must also be inserted by the binder at this time. Many printers, even from the earliest days, provided the binder with a printed register, listing every signature and the number of leaves it should contain, and sometimes, every plate and its location. The bookbinder also adds the endpapers. The book, thus assembled in gathered folded sheets, is ready for sewing.

Related Reading: Cheloniidae: Sea Turtles

Sewing the Book

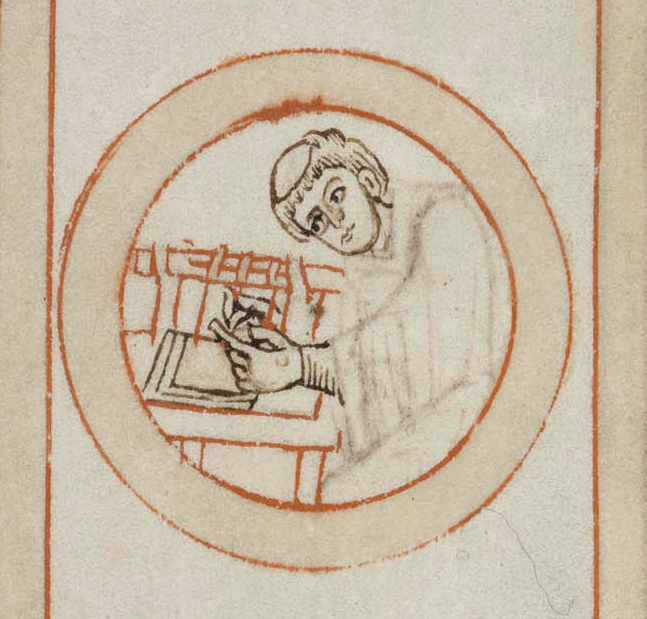

Although sewing can be accomplished in different styles, its most basic principles do not vary. The sewing frame that binders use today is identical to that used in the Middle Ages. The image below, which shows the apparatus, is from a twelfth-century manuscript held at the Staatsbibliothek in Bamberg, Germany.

It consists of a flat wooden base cut with a narrow channel along the long edge, with two threaded uprights on each end that support a horizontal bar resting on two wooden nuts threaded onto the uprights. The sewing supports are fastened to the top bar, let through the channel, and secured beneath it. Turning the nuts up raises the horizontal bar and creates tension on the sewing supports. The spacing of the supports is dictated by the size of the book being sewn and traditional aesthetics. The book is sewn from back to front (last signature to first). The back endpaper will be first. The binder lays the rear endleaves into position in relation to the sewing supports on the base of the sewing frame, and opens it at the center.

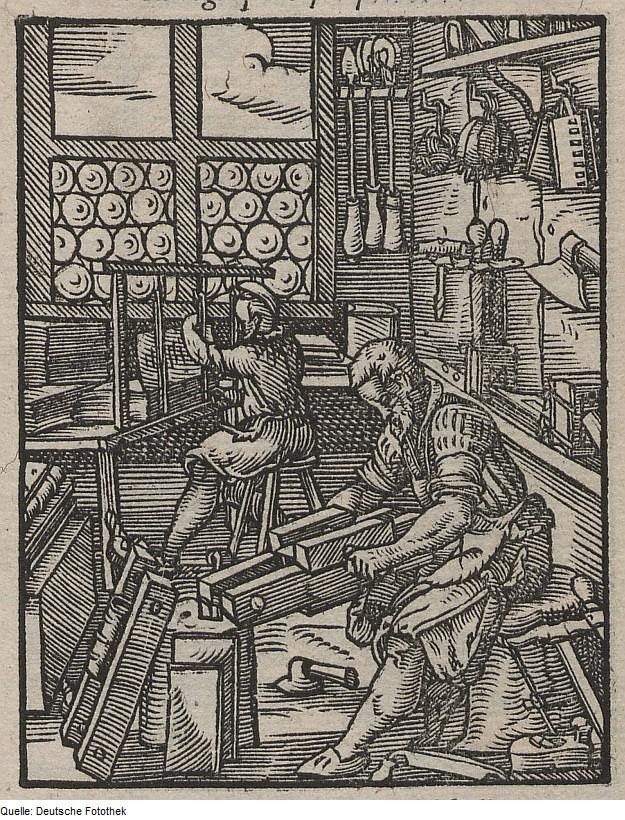

Der Buchbinder woodcut by Jost Amman from Das Sändebuch, 1568.

With one hand inside the center of the folded signature, the binder inserts a threaded needle through the signature at the fold, passing it to from the outside to the inside, then back out at the first sewing support, around the first sewing support, and back in, repeating all the way to the end of the signature. The next folded signature is placed on top, the binder puts the needle into the next signature, and so on.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=Z9JEGkAXHREQ7kNvwGGUot6&_nc_oc=AdmJSnx8eY0WSW4ZCrMwPTmQIsTfafOSyYaXtUeWluHXKdvbxi2gWaQXyIMLUy6-JA4&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=AoV5uqG6PIOkc0ElpTweaQ&oh=00_AfGYyzovpyG95A1lude-ZHqllmW1MuFyjDtCAn9ZfDXzyw&oe=68067791)