Making A Modern American Art: 1910 – 1920

The 1913 Armory Show

Inspired by time spent in Europe, around 1910, Arthur Dove became the first American artist to paint an abstract painting. At this time, abstract art was still largely unknown to many American artists. That would change in 1913 with the Armory Show, which became a catalyst for modern artists to embrace European influences.

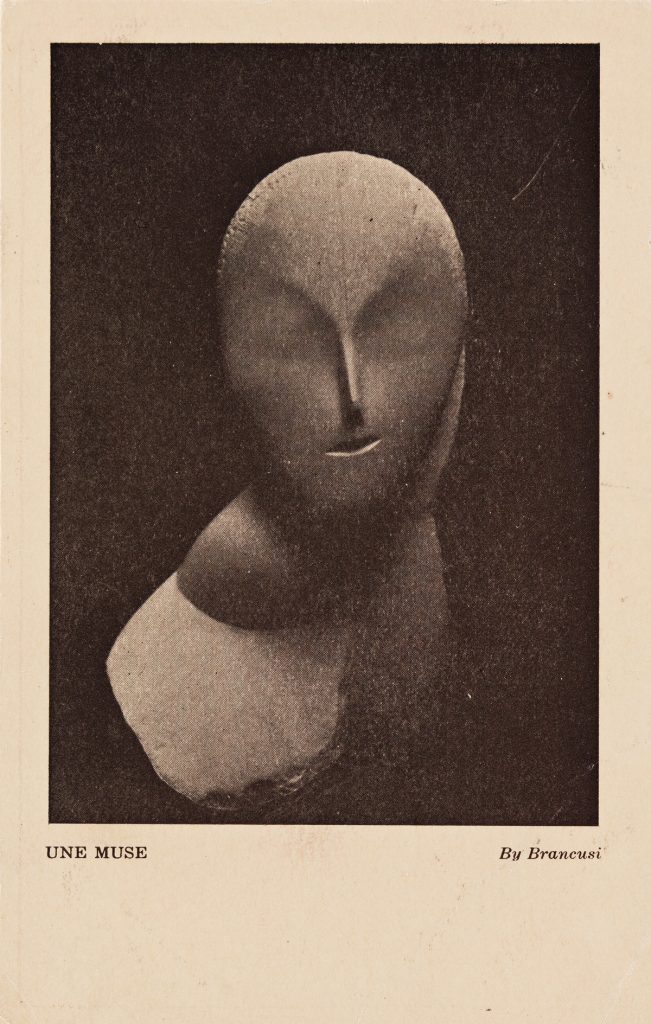

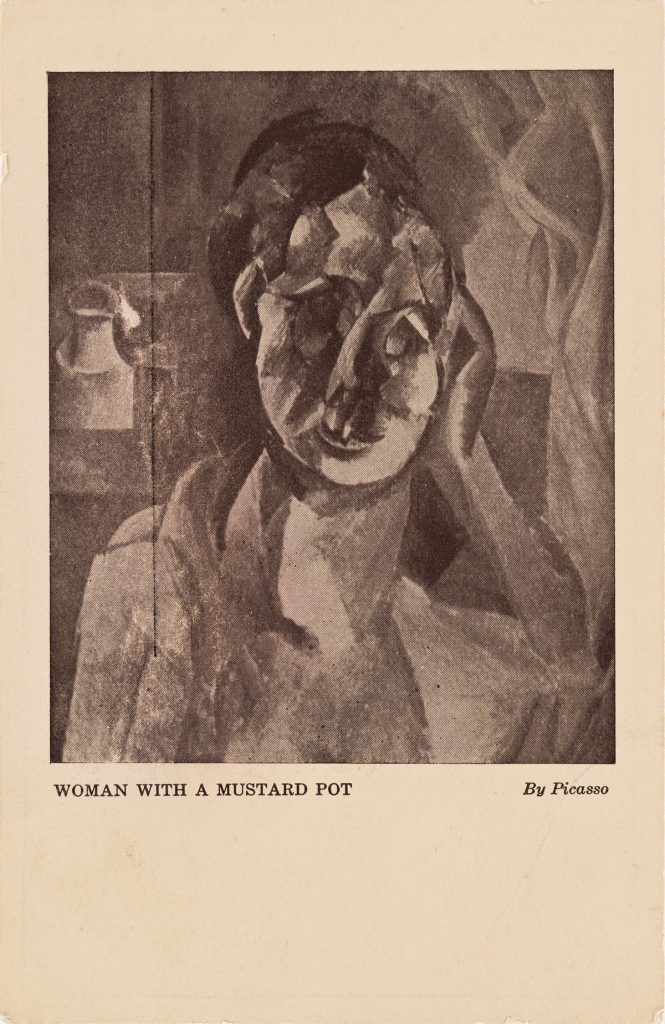

Pictured here is Brancusi’s Une Muse and Picasso’s Woman with a Mustard Pot.

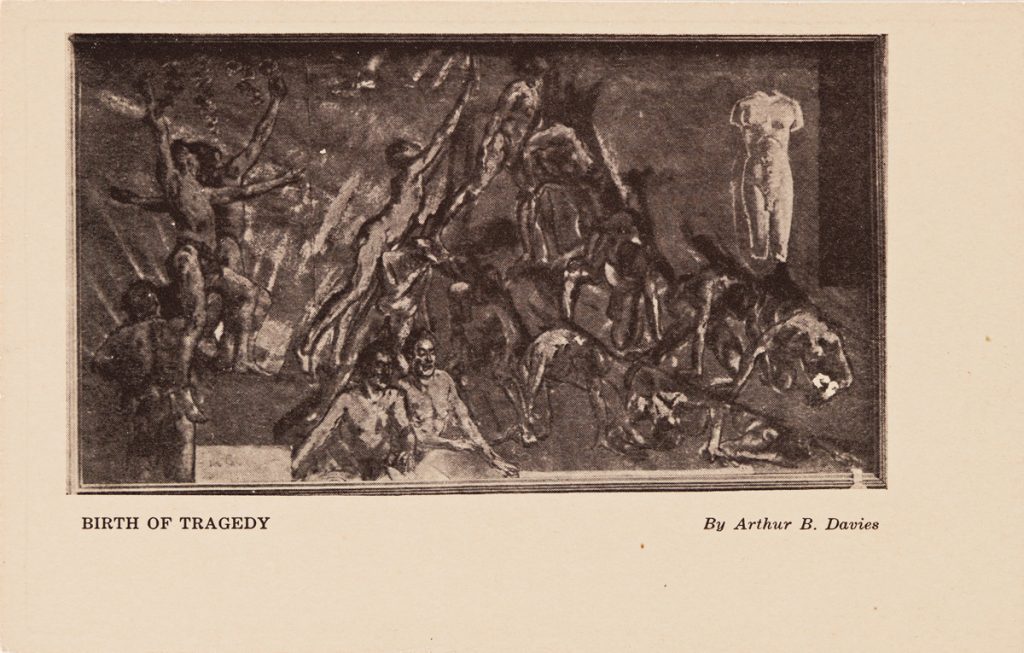

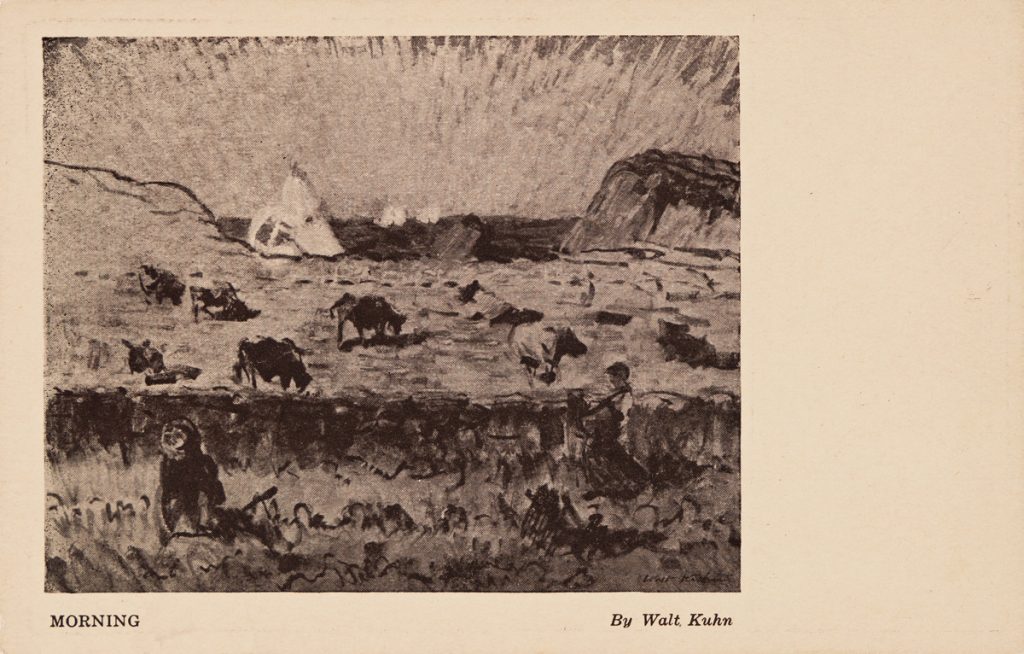

In 1911, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors was created to host a large invitational show that included European artists. Walt Kuhn and Arthur B. Davies ran the association and organized the exhibition, choosing the 69th Regiment Armory as the show’s location. The exhibition included three hundred artists, living and dead, and around 1,300 works of art. The earliest works were by Ingres, Delacroix and Goya; overall, it showed the development of modern art in Europe (although some key artists were excluded). It was a media sensation. The work of Marcel Duchamp created an uproar of revulsion and led to a debate on the nature of art itself. American artists were included in the exhibition, but their work appeared provincial next to their European counterparts.

Pictured here is Arthur B. Davies’ Birth of Tragedy and Walt Kuhn’s Morning.

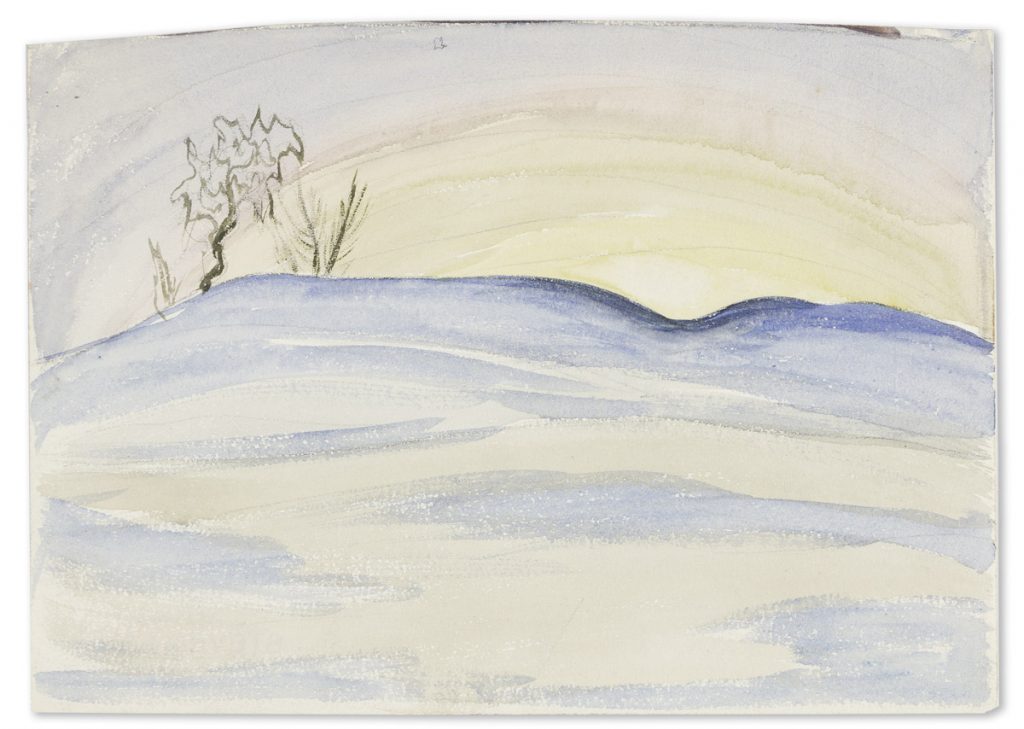

After the European prominence exhibited at the Armory show, many artists and dealers felt the absence of a national aesthetic and dedicated themselves to giving modernism a true American voice. During this decade, Stieglitz focused on exhibiting American artists; he had a close-knit circle including John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Max Weber, Arthur B. Carles, Abraham Walkowitz and Georgia O’Keeffe.

While Stieglitz’s space focused on exhibiting artists looking towards Europe and abstraction, the Whitney Studio supported those continuing to work in a Realist style. In 1914, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney started the Whitney Studio and held exhibitions to nurture artists. She favored realist artists such as Sloan and Luks. In 1918, it officially transitioned to the Whitney Studio Club and the space grew to include exhibition galleries, a squash court, library, salon and billiard rooms.

Related Reading:

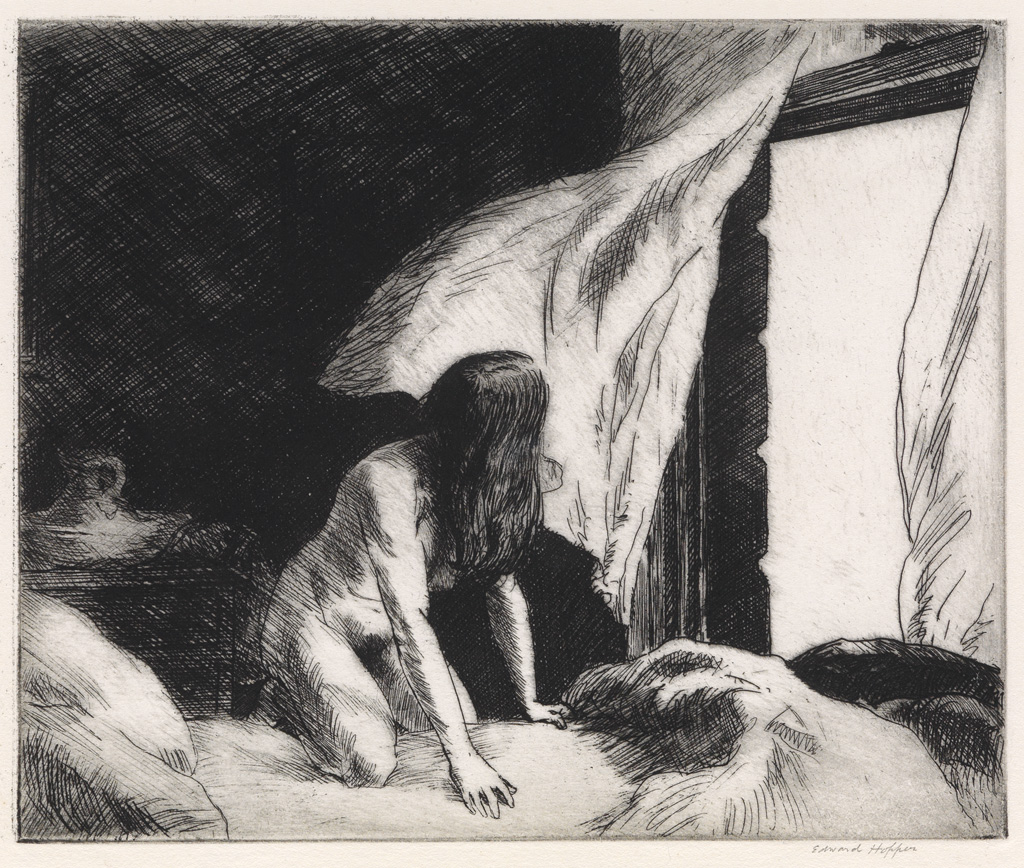

Hopper returned from his time abroad in 1910, and in 1913 settled in his studio at Washington Square Park North where he would remain for the rest of his career. His work was included in the Armory show; in fact, it was where he sold his first painting, Sailing. In 1915, Hopper took up etching and would produce around 70 over the next decade. He learned the etching process from Martin Lewis, another printmaker working in New York, who captured the city at night, exploring light and shadow. Through printmaking Hopper found critical and commercial success. He also found his signature style of depicting ordinary city or rural scenes with a pervading sense of loneliness. Printmaking was essential to developing Hopper’s artistic voice, and he noted that “After I took up etching, my painting seemed to crystallize.”

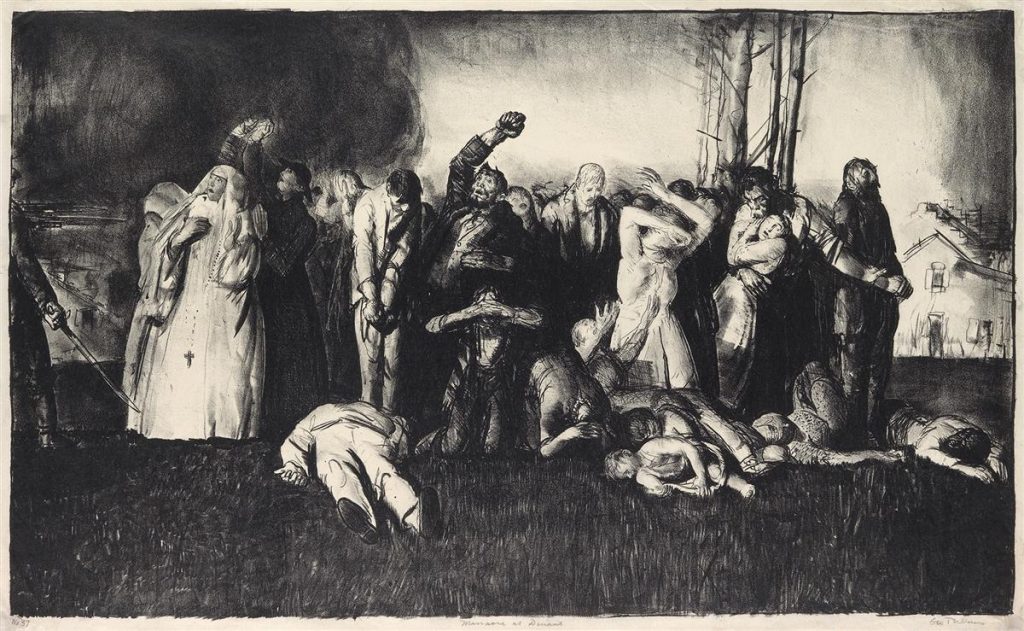

As artists continued to develop an American modern art, there were profound changes to global political stability. The carnage of World War I was impossible to ignore. Charles Burchfield recorded his fear of being drafted in his diaries and Georgia O’Keeffe’s brother enlisted immediately. George Bellows was explicit on his view of war in his work; his War Series was a group of lithographs that depicted atrocities carried out by the Germans. Stieglitz closed 291 in 1917 due to financial difficulties caused by the war and decided to focus on his own photography.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=Kjf2AzWLeY8Q7kNvwEQYrfY&_nc_oc=Adn_Uzi4Nwl1nHCsTtuLCIkthuYOWwKedtxovtcdMSYhpbHQGScR7QSzzN2rD0v-khE&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=g-mmtA5NszV6CS-yj0hzrg&oh=00_AfLaVPJlWLuG-Ri_DzbCxxewoKPr55kA2Mokrhefj8C6jQ&oe=6824CA11)