Artists Reclaiming the Queer Black Male Form

Within the LGBTQ+ community, preconceptions concerning members of color are steeped in racialization, classism, and social hierarchy. These stereotypes are applied willingly or subconsciously by the most privileged within the group: primarily upper class, white cisgender men, who use them to determine the worth of the LGBTQ+ minorities and the other-gendered. Racial fetishization stems from a plethora of sources: colonial-era pseudo-scientific ideologies, Eurocentric standards of beauty, and colonial fantasy regarding Black sexuality have led to Negrophilia and Negrophobia in those who identify as white LGBTQ+. These conscious or subconscious assumptions are destructive to the Black queer male members of the community and the true-to-life intersectionality of the LGBTQ+ population.

Corey Serrant on Queer Black Male Artists Reclaiming the Narrative of How They Are Depicted & Seen

Black cultural practitioners explore the Black gay male physical and mental state through a variety of artistic cues and symbols at their disposal. These tools help them to demystify racial and sexual stereotypes that plague the their white counterparts’ prejudiced work. Black gay male visual artists have worked to change how they are portrayed within their community and the general culture. They convey their bodies with dignity and familiarity versus the dominant culture’s gaze and fetishization. Sculptor Richmond Barthé, painter Beauford Delaney, and postmodern artists Freddie Styles and Glenn Ligon express Black queer male sexuality and identity on their terms free of prejudice and racial stereotypes. They are but a few of the artists that portray the Black gay male body in opposition to their white counterparts.

Richmond Barthé

Richmond Barthé’s Feral Benga represents the culmination of his study of the figure in sculpture, anatomy, and dance in the 1930s. It is Barthé’s pioneering realization of an ideal Black male nude. François Féral Benga was a Senegalese cabaret icon of avant-garde Paris and the Harlem Renaissance who existed in openly gay creative circles and is known to have had multiple lovers throughout his life. Grander in scale than its actual size, Feral Benga was one of the achievements of Barthé’s lifelong body of work.

The sinuous curves and musculature of the body exude organic sexuality and confidence. As an early example of homoerotic sexuality created by a Black queer male artist, the sculpture does not act as a device for a fetish or hypersexualization. It is a pure expression of Black male queer sexuality and glorification of the Black male form. The African-themed cabarets of interwar Paris employed scandalized tropes of a fetishized deviant to entice liberal white men and vex conservative white women. The dancers on stage used the white gaze to empower their performances and gain careers and personas on and off stage. Feral Benga negates the traditional sexual and racial binary relation in which the classical nude exists. Benga and Barthé’s commodification of fetishism overcomes the bias that could have been applied to the sculpture if its creator were white.

Related Reading: New Record for Richmond Barthé in June 4, 2020 Sale of African-American Fine Art

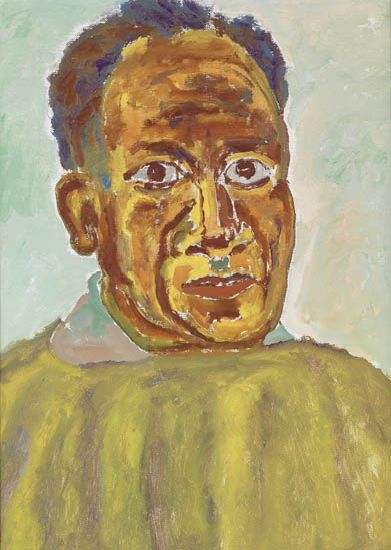

Beauford Delaney

Modernist painter Beauford Delaney had a tight-knit community of friends and held many professional successes throughout his life; yet he remained an isolated individual. David Leeming, in his 1998 biography Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney, presents the artist as having led a very “compartmentalized” life in New York. In Greenwich Village, where he lived and worked, Delaney became part of a gay bohemian circle of mainly white friends, but he was uncomfortable with his sexuality. When he traveled to Harlem to visit his African American friends and colleagues, Delaney made efforts to ensure that they knew little of his other social life in Greenwich Village. He feared that many of his Harlem friends would be uncomfortable or repelled by his homosexuality. His upbringing in Knoxville, Tennessee, with parents who were former slaves bestowed him with dignity and intelligence, but growing up in the Deep South led to traumatic experiences with racism at a young age. Leading a rich yet hidden life led to an agony Delaney tucked away from his friends and acquaintances.

Delaney’s Self-portrait deals with the duality of being a Black queer man in mid-century America. There is a feeling of familiarity yet otherness in the self-portrait. The over-the-shoulder pose with his back faced towards the viewer and his face-forward gaze matching the viewer makes him seem distant and secretive, yet inviting and analyzing. His eyes survey the viewer and match our gaze to see if we are aware of his innermost secrets. The partial invitation into the world of the artist tells us that there are parts of himself he is willing to share yet, there are details that he is unwilling to divulge. The image makes him an ambivert with a hidden sexuality yet outgoing facial expression. It exists of its own autonomous subjectivity and challenges the gaze of the viewer.

“Keep the faith and trust in so far as possible. Love humility and don’t mind the insinuations that cause sorrow…and loneliness and limitations. We learn self-reliance and to hear the voice of God, too…and how to…not break but bend gently. Learning to love is learning to suffer deeply and with quietness.”

Beauford Delaney

Delaney’s solitary persona, driven by his upbringing and a society that subdued his sexuality, led to a state of contemplation and revelation. However, his mental state suffered from not living his truth.

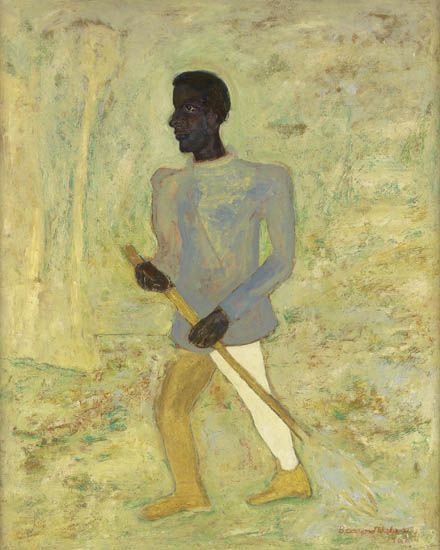

Another work made during his Paris period, La Balayeur, is a metaphorical self-portrait—an isolated man of African descent working in a foreign place, with the broom representing the artist’s paintbrush. Delaney has captured the Black male form (one that could possibly be his) and composed a narrative that is limitless in the eyes of the viewer. The figure bathed in yellow is solitary, enabling, and dignified. His portrayal of an anonymous street worker is a familiar experience common to Black men, the isolation of walking down the street and being ignored by his fellow man, or the phobia of him and what his presence stereotypically represents. The skin color of the street sweeper acts as a marker of valor and makes the figure seem heroic in his everyday task.

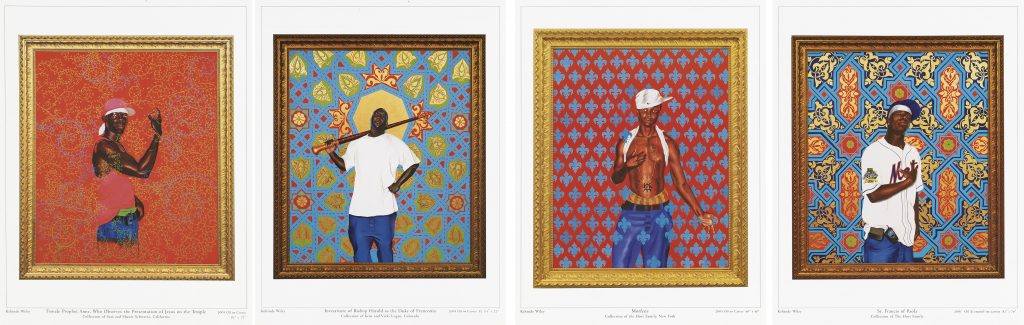

Kehinde Wiley

Kehinde Wiley’s practice is focused on rewriting the canon of Black art and art history. Passing/Posing, Paintings & Faux Chapel is a portfolio with 17 color offset lithographs that depict African American gay men styled in a Black heteronormative fashion set in different baroque backgrounds. The men in Passing/Posing are “passing” or “posing” as heteronormative Black men. They are dressed in a manner of a stereotypical Black man that society has codified as the archetypal Black man. Wiley’s models, as the title reads, are passing as heterosexual Black men. “Passing” in the Black LGBTQ+ community is an act of reification of acceptance from the overarching heteronormitive society. These stereotypes that our culture has subscribed to and placed upon Black queer men are irreparably damaging. Wiley uses these images to attack the gender normative roles that Black queer men that are believed to subscribe. He uses the Black queer body as an agent to negate social prejudices of Negrophilia and Negrophobia that the white male LGBTQ+ community unknowingly or knowingly subscribe.

The political context of the Black queer male in the LBGTQ+ community is one of invisibility or footnote. These images negate stereotypes of Black men while glorifying the Black queer male body in the tradition of a European noblemen. These Black queer male bodies are free of erotic symbols, fantasies, and desires of general society while surpassing class and race differences. Their identities are sovereign, solely belonging and adhering to themselves.

Related Reading: Artist Profile: Kehinde Wiley

Freddie Styles

Georgian artist Freddie Styles has produced an extensive body of work in non-figurative art in both painting and collage over his career. The Red Door depicts a nondescript red door partially open leading to a mysterious entryway. The artist said of this work:

“This piece is the central panel of a triptych I did in 1980 depicting the block on Hunter Street, now MLK. between Ashby and Mayson Turner Streets in Atlanta, GA. This panel illustrating a red door slightly ajar revealing a silver lining is the entrance to an enchanted place where young gay men dream of becoming of age to enter. The Red Door is the entrance to the legendary gay club known as the ‘Marquette,’ sometimes referred to as the “Quesy.”

Marquette Restaurant & Lounge is a queer safe space and home for the Black members of the LGBTQ+ community in Atlanta, where they can listen to music, dance, and embrace their authentic selves without the leer of the white gaze and free from sexual racism. Their bodies are free to move rhythmically and interact with each other without the pretenses of cultural stereotypes. Marquette allows its patrons to be free from the politics of visibility. Not having spaces in which Black queer men can live their truth is detrimental to understanding themselves.

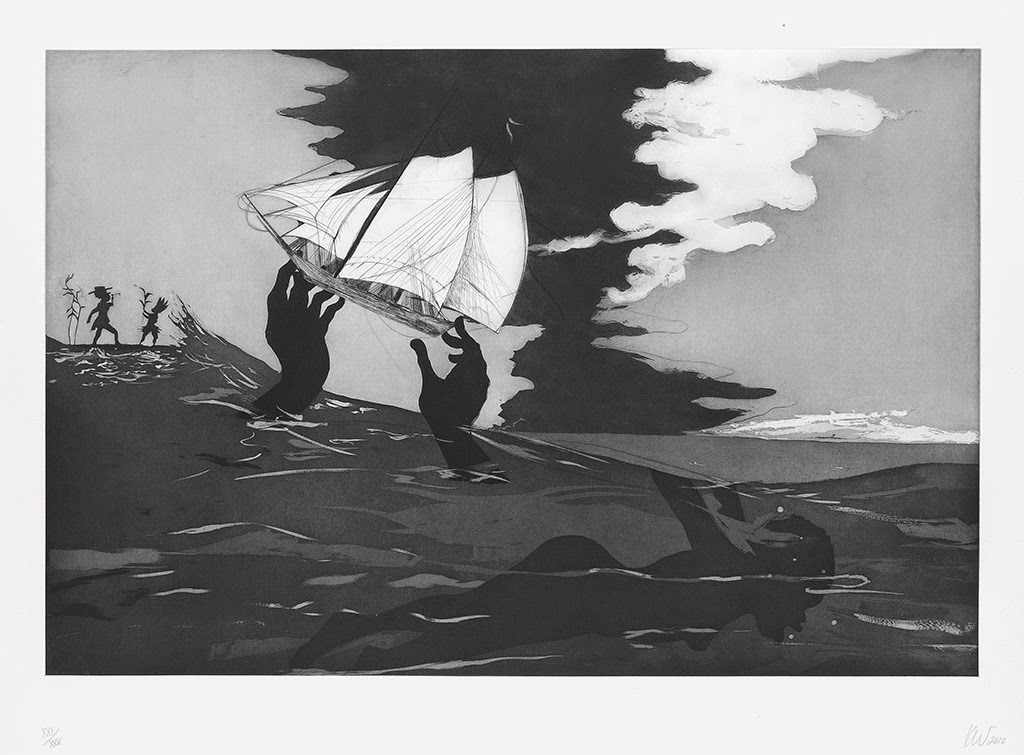

Glenn Ligon

Glenn Ligon’s notable print is a quote from the prologue of Ralph Ellison’s seminal 1952 novel on urban Black masculinity Invisible Man.

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. . . . I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

Ligon’s use of the prologue on black Rives paper makes an impactful statement to the feeling of invisibility and societal stereotypes of what Black masculinity and its intersection and influence on Black queer men is. The artist’s sexuality plays a role in the identity politics of the artwork. It is known that Ellison held a moralist anti-gay political view. Scholar and biographer Arnold Rampersad notes in his biography on Ellison that he accused homosexual officials of having “hounded” him out of college. Also, found in his Ellison’s papers, he wrote of James Baldwin in 1953, “He doesn’t know the difference between getting religion and going homo.” Ellison’s view of homosexuality strengthens Ligon’s use of his text in analyzing the feeling of invisibility by Black queer men. Ligon’s post-modern analysis of the Black queer body from Ellison’s prologue acts as an expression of rejection of the white gaze with the black color of the paper and text. It acknowledges toxic stereotypes of Black masculinity and the obscured identities of Black queer men within the LBGTQ+ community.

A second work from Glenn Ligon, Untitled (Barbershop), is a commentary on the role of the barbershop in the Black community—while a safe space to Black masculinity, to Black queer men, it is a space of contempt, a homophobic institution where they are not accepted and may be physically harmed. Upon passing, their bodies go into a state of fight or flight when interacting with the space, its participants, and the symbolism of the barbershop. The barbershop acts as a haven to Black men in their communities yet rejects Black queer men that are not accepted or cannot pass in the general heteronormative culture. Their bodies are either used and defiled by the larger LGBTQ+ community or face rejection in the masculine-centric Black community.

Ligon’s work assesses the general view of Black men as paralyzing and narrow, reducing them to the thug on the corner while the Black queer body is invisible in the Black community, lost in a void between blackness and queerness. This invisibility inflicted on Black queer men has denied the complexity of who they are as human beings. It has constantly threatened their sense of self and undermined their ability to realize their full potential— as well as suffering from exploitation from our fellow members of the LGBTQ+ community. The white male cis-gendered members of the LGBTQ+ see African American gay men as aggressive and dominant symbols of hyper-heterosexuality that are at the mercy of their whims. Untitled (Barbershop) is a member of Black cultural production tied to masculine ideologies held by Black and white American communities.

Visual artists such as Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe (in particular the 1986 show entitled Black Males) perpetrated cultural stereotypes and fetishes upon Black queer men. Focus on the phallus, among other stereotypes such as natural athleticism and an over-sexualization of the body, led to a hypersexualization of the Black queer male body. Haring and Mapplethorpe’s works othered the African American Gay Male as a cultural artifact, and as a result, reduced it to a vessel to be filled with sexual fetishes. Eventually, the sexual racism shrouded in their work fed into the reduction of humanity that is experienced by Black queer men.

Richmond Barthé, Beauford Delaney, Kehinde Wiley, Freddie Styles, and Glenn Ligon produced artworks that are in sole ownership of the manifestation of their physical entities. They chose these modes of representation that best suit them, without the gaze of the heteropatriarchy and white cis-gendered gay men. Varying by medium and art historical precedent, they are inspired by muse, literature, social context, or the artist themself. The visual codes of modernism and postmodernism are used to shape the depth of the Black gay male identity. These works are not bound to traditional theories and realize the intersectionality of the artists and their subjects. The expression of Black queer sexuality and what shape it takes are in alignment with the artist’s terms. The spectator looking into the Black queer mind and psychological state are viewing works from beings that exist beyond physical and racial stereotypes. The absence of the phallus in the imagery enables a deeper understanding of the Black queer identity. These works are testimony to the fact that Black queer men are more than racial stereotypes. The Black gay male unconscious is a departure for multiple identities, experiences, and overall intersectionality of being.