A Brief History of AfriCOBRA

The AfriCOBRA movement was borne from the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements. The collective was founded in 1968 by Chicago based artists: Jeff Donaldson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu and Gerald Williams. The founding members had been previously associated with The Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), which was founded in 1962, and most notable for the famous Wall of Respect mural in Chicago.

The Founding of AfriCOBRA

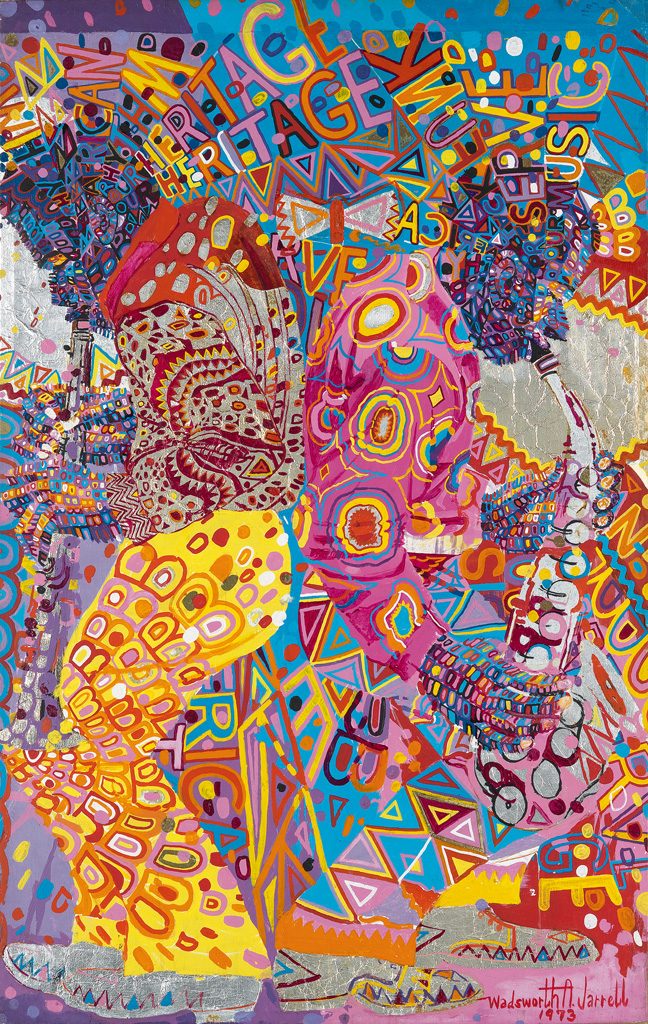

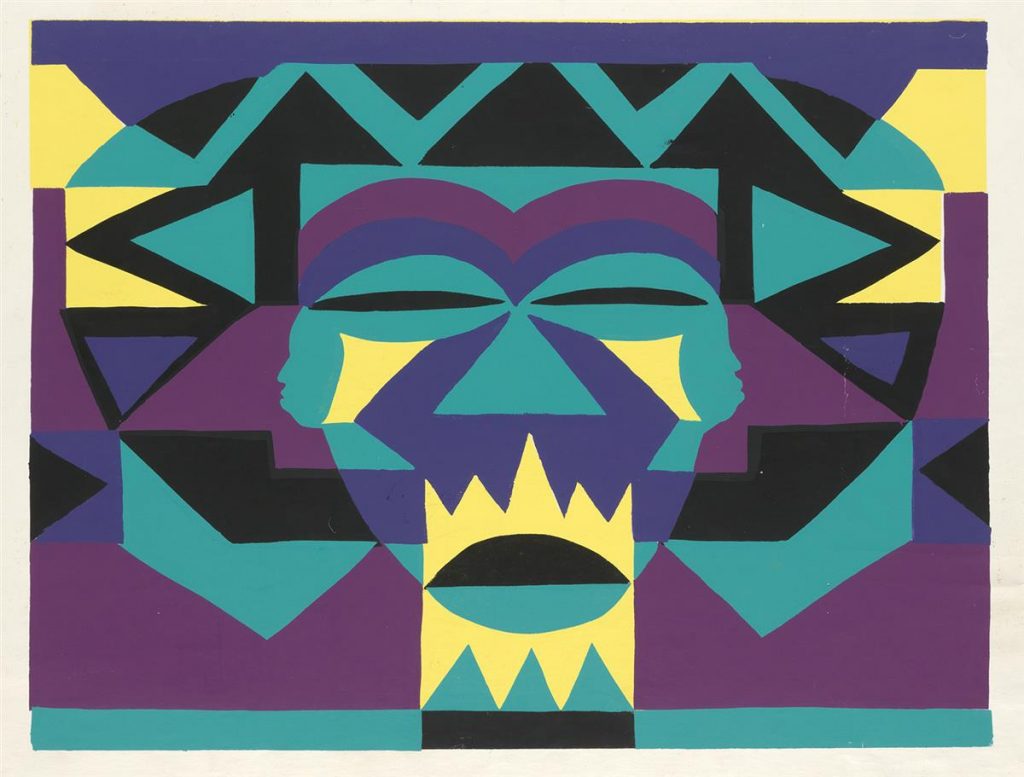

The philosophical mission of AfriCOBRA was to create images committed to a sublime expression of the African diaspora that would be identified by and reflected on by all black people. AfriCOBRA’s goal was to unite all members of the African Diaspora–they wanted to eliminate the western idea of the self and embrace the progress of the community. The founding members wanted to honor the past, contextualize the present, and prepare for a bright future. To this end, they created a mission statement and tenets that became a manifesto, written by Jeff Donaldson. The artists believed that through collective consciousness their art and objects would propel social and political change in their communities. The aesthetic principles of AfriCOBRA adhered to the ideals of “bright colors, the human figure, lost and found line, lettering, and images which identified the social, economic and political conditions of our ethnic group.”[1] They wanted to embrace “specific visual qualities intrinsic to our ethnic group.”[2]

The Artistic Expression of AfriCOBRA

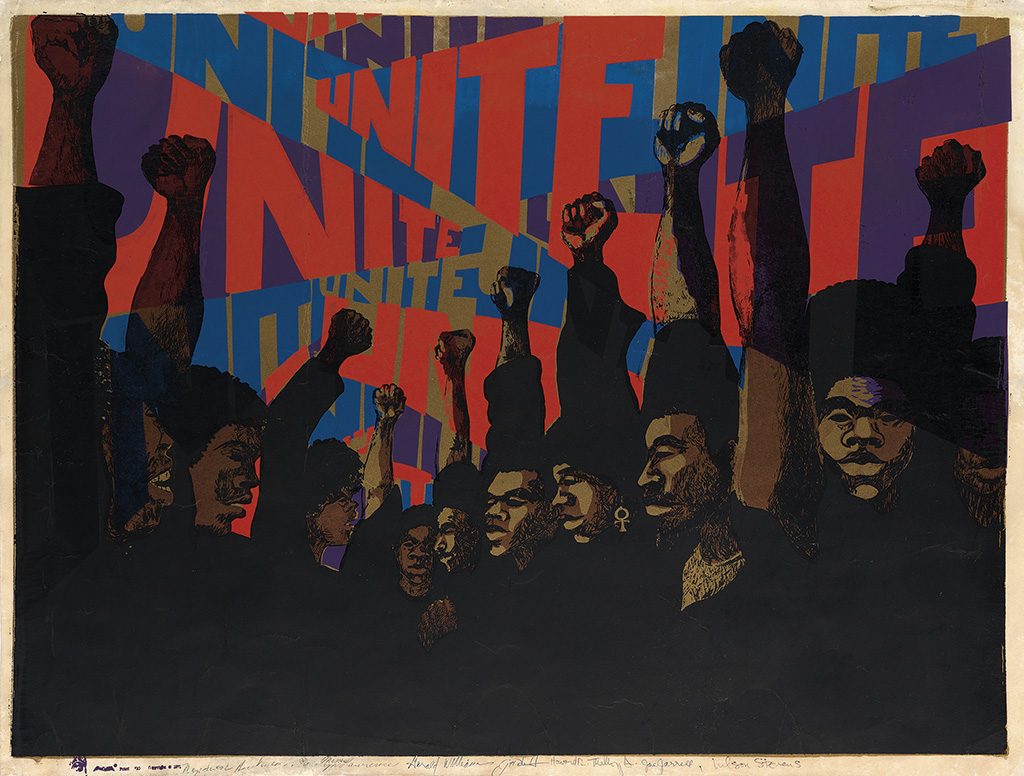

The artists of AfriCOBRA had no reason to appeal to critics that omitted them from the timeline of art and concurrent movements. The works produced by these artists were intended to empower the black community. They strove to create images that expressed the depth of black culture and Pan-Africanism, embracing a family tree with branches stretching beyond the United States, reaching the Caribbean and African ancestral homes. Through the application of printmaking (many of the members were painter-printmakers) the artists sought to reach all black people by producing multiples that people could live with and that would reinforce their values. The charged imagery in the posters reinforced the ideal of AfriCOBRA to invest in the black consumption of blackness, as opposed to what the movement saw as the dominant culture’s practice of collecting of African American culture.

“[Our art] must communicate to its viewer a statement of truth, of action, of education, of conditions and a state of being to our people. We wanted to speak to them and for them, by having our common thoughts, feelings, trials, and tribulations express our total existence as a people.”

-Barbara Jones-Hogu

Related Reading: Augusta Savage to Zoë Charlton

The First Exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem and the AfriCOBRA Legacy

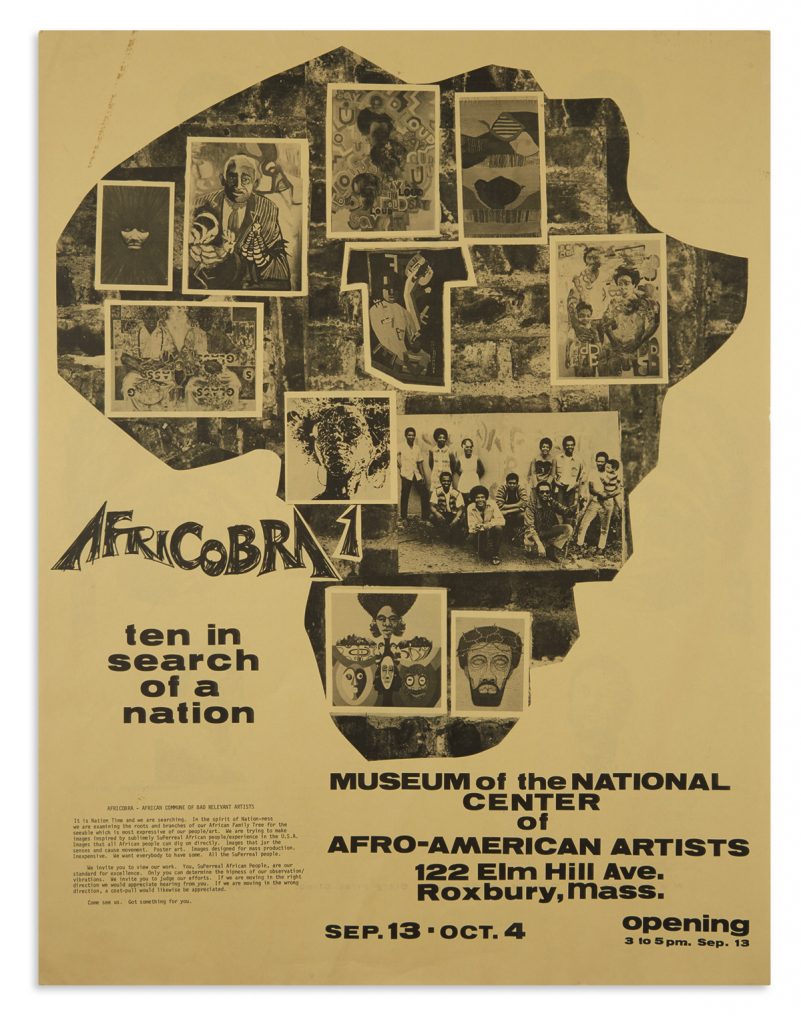

In 1970, the group prepared for its first major exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Ten in Search of a Nation. The work they produced was created with a singular purpose: to educate. They did not want to promote individual gains over their unified message. Poster reproductions of the works were given to exhibition attendees to take home, to better experience the spirituality and symbolism of the art shown.

AfriCOBRA’s 1977 participation in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) led to the trans-African legacy of the movement. Held in Lagos, Nigeria, FESTAC brought together diasporic artists and thinkers from the performing, visual and literary arts.

The evolution of AfriCOBRA reverberated in the artistic communities of Washington, DC, New York, and Lagos. The movement and its artists were overlooked by critics at the time, and are only now being incorporated into art history, institutions, and the art market. Still, their legacy is one of inspiration for other African-American artists who embrace community, education, and diasporic creativity.

Recent Museum Exhibitions Featuring AfriCOBRA

Recently there has been a brilliant recognition and revitalization of the work of the collective. Through exhibitions at galleries, institutions and biennials, AfriCOBRA and its artists are receiving the accolades they deserve. The landmark exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at the Tate Modern was the catalyst to the examination of the artwork produced by the movement’s artists. The exhibition traveled to multiple institutions in the United States, including Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, the de Young, and The Broad. AfriCOBRA: Nation Time, a collateral event of the 58th Biennale di Venezia held at the palazzo of Ca’Faccanon, raised global awareness of the movement and acted as a second chapter of AfriCOBRA: Messages to the People, which premiered in 2018 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami.

More from Corey Serrant.

Do you have work by an AfriCOBRA artist we should look at?

Learn about how to consign to an auction, and send us a note about your item.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=QlZg0o3Vx4oQ7kNvwHlPDYS&_nc_oc=Admkx5CH3-5gNl9kFtE07uGBWzC1TrU8LutoXTk30m77fiWC0m2_oIjIUSQBbJE8mA8&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=LKk1gtEmoFkqdxHMdO-bqg&oh=00_AfK7zXwFsWEqv8D6xhU0wob_5asRzpiOa4hEb4NHZ6Sw9w&oe=682572D1)