The Woman’s Eye: Seven Women Photographers to Know

Though utilizing a variety of artistic practices and genres, from portraiture, self, and of others to photojournalism and social documentary, the photographers highlighted here have all used the camera to record social changes and reveal social conditions as a way of bearing witnesses, both reflecting the world they find and seeking new ways of seeing. Their works also reveal how the portrait and documentary genres interweave to create new narratives about the times in which we live.

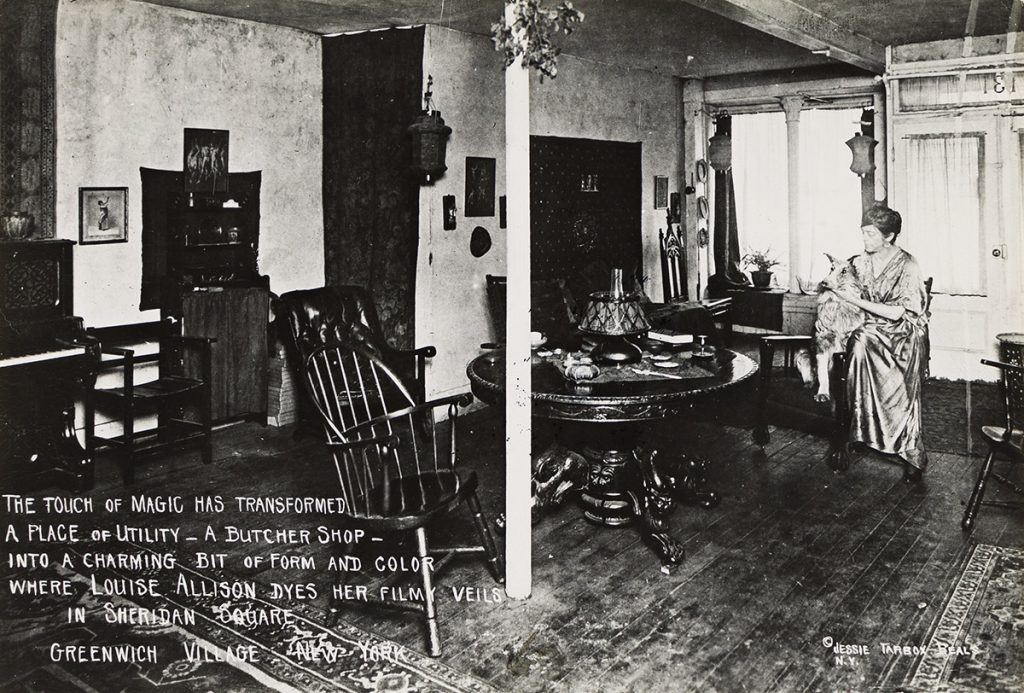

Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870-1942)

Jessie Tarbox Beals is to be praised not only for being one of the first women night photographers but also for her pioneering role in news photography and for her tenacity in becoming the first published female photojournalist in the United States. Tarbox Beals ventured to work in situations generally thought too rough for a woman, wandering the streets at night with her large 8×10 view camera and all the material that encumbered it: lenses, a bulky wooden tripod, holders, and heavy glass plates.

Born in 1870, she opened her studio as a freelance news photographer on Sixth Avenue, New York, in 1905. She took on a variety of photographic assignments, ranging from portraits of society figures to her well-known photographs of the St Louis World Art Fair and Bohemian Greenwich Village, NY. After a brief move to California in 1928, the Great Depression brought her back to the East Coast in 1933, where Beals lived and worked in Greenwich Village until her death in 1942.

Tarbox Beals shot with such dexterity and sensibility that her work summarizes her talent as a photojournalist. Her images were so powerful that they superseded the texts and could be used as the stories themselves. As such, she paved the way for other women photographers who came after her, such as Berenice Abbott, Helen Levitt, and Margaret Bourke-White.

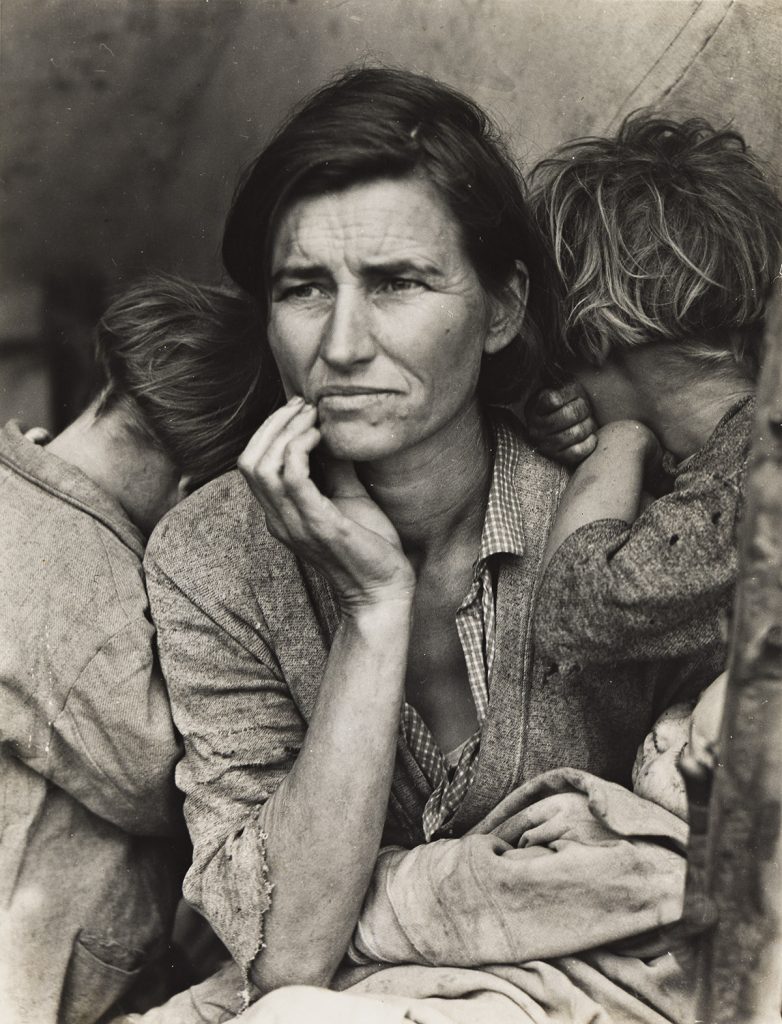

Dorothea Lange (1895-1965)

Dorothea Lange believed strongly in the camera’s ability to effect change and powerfully illustrate injustice and inequalities. Her images are both deeply empathetic and outraged, and her methods—open, instinctual, responsive, and intimate—created some of the most enduring and iconic images from the period. “Open yourself as wide as you can, like a piece of unexposed, sensitized material,” she wrote.

Lange began her career as the principal of a portrait studio, photographing San Francisco’s elite families. Her aesthetic awareness of design, composition, and the subtleties of light was matched by a keen sensitivity to the human condition. Ambitious, Lange’s immediate social circle included Imogen Cunningham, Anne Brigman, and Consuelo Kanaga. But with the Great Depression and the collapse of America’s social fabric and economy, Lange’s business faltered. She shifted focus, taking herself out of the studio and into the street. Her studies of demonstrations, protests, and unemployed workers seeking assistance in the early 1930s captured the attention of Roy Stryker, director of the Resettlement Administration. The RA, a New Deal agency later renamed the Farm Security Administration, was tasked with helping the rural poor.

Migrant Mother’s creation and subsequent transformation into a cultural icon is well documented. Lange made this image, along with six other frames, of the same woman, Florence Owens Thompson, in 1936. Taken in early March, by the 11th of that month, it had been reproduced to thousands of newspaper readers for the first time (in the San Francisco News accompanying an editorial titled “What Does the ‘New Deal’ Mean to This Mother and Her Children?”). Since then, its power and visual impact have only grown and multiplied, becoming one of the most recognizable and reproduced images in the world. It has not lost its ability to move and connect, a testament to Lange’s enduring empathy and abilities as a photographer.

After an early marriage to the painter Maynard Dixon, whom she divorced in 1935, Lange married the progressive agricultural economist Paul Schuster Taylor. They formed a professional partnership that lasted until her death. As a writer-photographer team, they collaborated on a popular publication about migrant workers during the Dust Bowl titled American Exodus, 1939, a beautifully designed book that featured Taylor’s descriptive text and Lange’s richly printed photographs.

In 1941, Lange received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the first woman was awarded the honor. Shortly after, when Japanese-Americans were involuntarily transferred to Manzanar, an internment camp in California, Taylor and Lange were among those protesting the mass incarceration of American citizens. Lange, on assignment for the War Relocation Authority, photographed families as they were rounded up by soldiers and ushered onto buses and trains, later visiting the camp and recording detainees adjusting to daily life in the facility. Lange’s pictures reflected her political outrage. Subsequently, the federal government seized her negatives.

Diane Arbus (1923-1971)

Diane Arbus began her career working on commissions and freelancing for magazines as a commercial photographer but moved to documentary after studying with Lisette Model, her mentor, in the 1950s. Model’s influence caused Arbus to focus her artistic practice on personal projects, which led her to portray not only ordinary people but also outsiders or people rarely chosen as subjects, such as travesties, dwarfs, nudists, and even residents of elderly homes, as the center of her practice. Because her images sometimes seemed grotesque, they generated harsh criticism, including from Susan Sonntag, who reproached her for mocking her subjects. Arbus defended herself by asserting to photograph only what she saw, not by constructing another reality. It is true to maintain that Arbus’s photographs not only reveal a certain talent but also confirm her instinct to unveil the photographic potential of her subjects.

While Arbus achieved some institutional recognition and renown during her lifetime, major posthumous exhibitions have since praised her work, from the Venice Biennale in 1972, in which Arbus became the first photographer to be included, to her retrospective shown in Arles in 2023, confirming that her work is still very much relevant and acclaimed.

Related Reading

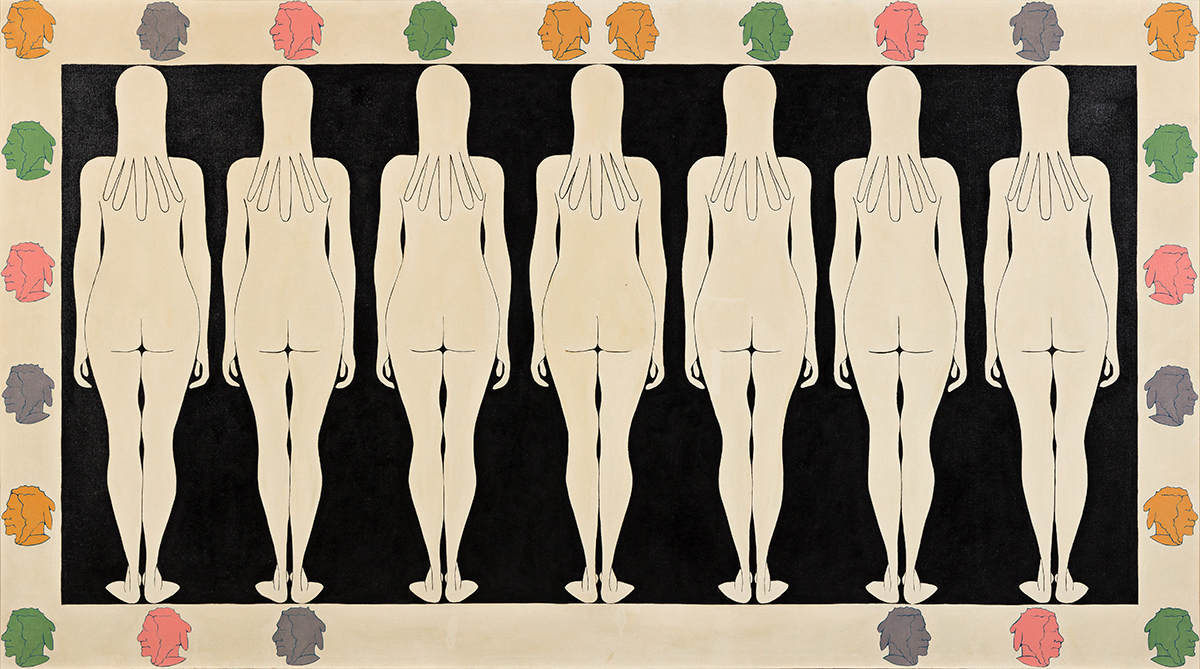

Cindy Sherman (1954- )

Cindy Sheman’s Untitled Film Stills, a body of work that includes 70 black-and-white photographs, is one of the seminal bodies of work of the twentieth century. In each, Sherman posed as a generic female film character, or more specifically, as an actress playing a character, modeled on a scene that could be from the 1950s or 60s Hollywood, film noir, B movies, or a European art house film. Rarely do these images reference specific works, but rather are deliberately generic, recalling types: the working girl, the vamp, the lonely housewife, and others. All of Sherman’s Film Stills feature the central character alone, though she often seems to be looking just off-camera, her focus elsewhere, placing us, the viewer, in the uncomfortable role of voyeur. By keeping the scene open to interpretation, by suffusing the scenes with both danger and suspense and beauty and seduction, Sherman inserted herself into a dialogue about the role of stereotypes and femininity in contemporary culture.

Sherman’s series began just after she graduated from Buffalo State College and moved to New York. She shot the initial images in her apartment but quickly moved out to the streets of the city. Originally exhibited at Hallwalls in Buffalo in slight variants and mimicking the publicity still format, the 8×10 glossy photographs initially recalled disposable prints rather than works of art. Each photograph was deliberately priced at $50 when they were first exhibited. “I wanted them to seem cheap and trashy. Something you’d find in a novelty store and buy for a quarter. I didn’t want them to look like art” (E. Respini, Cindy Sherman, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012, p. 21-22).

In the essay “The Making of Untitled,” Sherman wrote: “I suppose unconsciously, or semiconsciously at best, I was wrestling with some sort of turmoil of my own about understanding women. The characters weren’t dummies; they weren’t just airhead actresses. They were women struggling with something but I didn’t know what. The clothes make them seem a certain way, but then you look at their expression, however slight it may be, and wonder if maybe “they” are not what the clothes are communicating. I wasn’t working with a raised “awareness,” but I definitely felt that the characters are questioning something-perhaps being forced into a certain role. At the same time, those roles are in film: the women aren’t being lifelike, they’re acting. There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity.” (Cindy Sherman, The Complete Untitled Film Stills, (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2003)

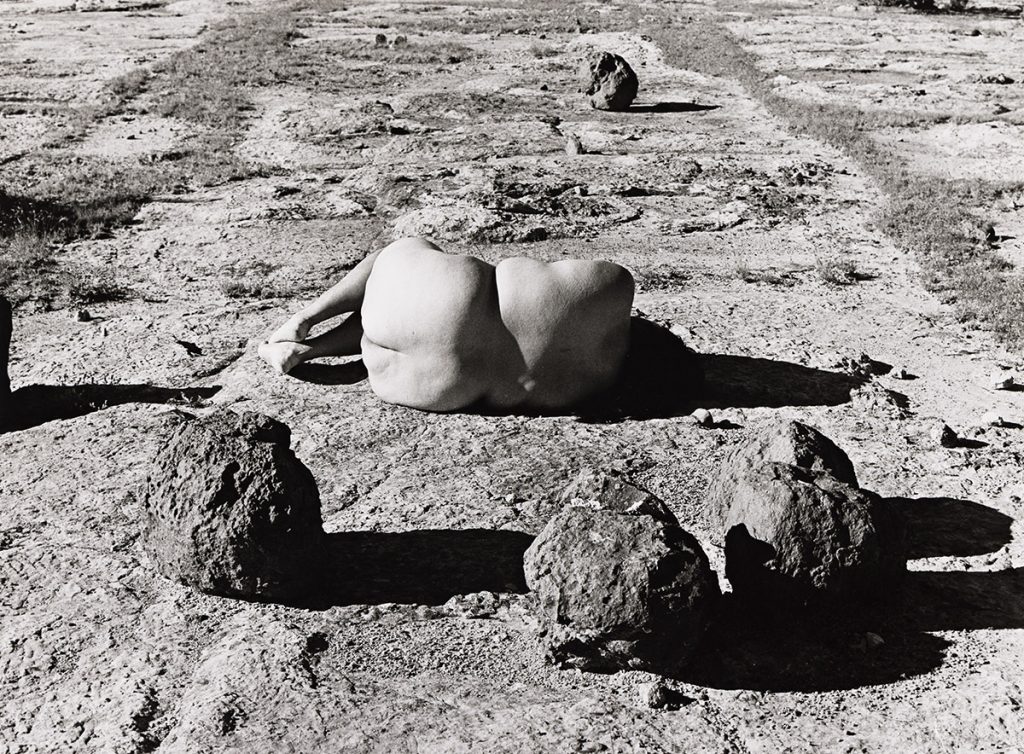

Anne Brigman (1869-1950)

Preferring pants to skirts, the wild Sierra Nevada Mountain range to city streets, and suffrage to traditional domesticity, Anne Brigman’s radical work sought freedom through the challenging of visual norms. By moving out of doors and into the wilderness, a place traditionally seen, traversed and photographed by men, and by using her own nude form as subject, Brigman established herself as a visionary, a trailblazer, who set forth on a path we now recognize as feminist, long before the term feminist art was coined. “Fear is the great chain which binds women and prevents their development, and fear is the one apparently big thing which has no foundation in life,” she told The San Francisco Call in 1913, “Cast fear out of the lives of women and they can and will take their place…as the absolute equal of men.”

Brigman positioned her female models (often using herself as a model), entangled with and engaged with trees and rocks, and actively connected with the natural world. Arriving at these remote locations required a long, difficult journey, including bringing heavy camera gear. She often stayed for days, executing carefully planned compositions, which she then further manipulated and altered in the darkroom, obscuring and enhancing the forms. Her imagery expresses a harmony with nature as well as a reclaiming of space and self-expression, though the Pictorialist sensibility of the finished work may belie her pioneering form of expression to the modern eye.

Laura Aguilar (1959-2018)

As outlined in Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography (Ann Wolfe, Susan Ehrens, et alia, Nevada Museum of Art, 2018), it is not an exaggeration to draw a line from Brigman’s pioneering work to the work of Laura Aguilar, who also placed her own form within nature as a mode of expression and protest. Aguilar’s groundbreaking work focused primarily on the queer, Latinx, and working-class communities of her native Los Angeles, using portraiture to examine gender identity, class, and body politics, as well as mental health and representation within the art world. Some of her early series of work focused on the communities of which she was a part, including Latina Lesbians, How Mexican is Mexico, and Plush Pony, the last of which documented patrons at a working-class lesbian bar. But far more than a documentarian, Aguilar also turned the camera on herself, using her body to create vulnerable images investigating her own exploration of identity and relationship with her body and mental health. Now considered vastly ahead of her time, Aguilar posed herself as an element of the Southwestern landscape, curling her body around rocks or curved on the ground, her face turned away or shielded from the viewer. She is both seen and unseen in work that is both poetic and poignant.

![Grace Meschery-McCormack shares about two copies of Fernando de Rojas’s ‘La Célestine,’ including a limited edition copy illustrated by Pablo Picasso.

At auction April 22. Learn more about the works at the link in our bio.

#Rarebooks #rarebookdealer #antiquarianbooks #auctions

_______________________________________

Music Credit:

Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘The Trout’, D. 667 - IV. Andantino – Allegretto

Music provided by Classical Music Copyright Free on Youtube [https://tinyurl.com/visit-cmcf]

Watch: • Schubert - Piano Quintet in A major ‘...]](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491443494_18499096345036585_5935932878956098058_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=107&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=u_iWjSzBq6AQ7kNvwGP43px&_nc_oc=Adm2-RoP-ycffpqdlTNCCefFvNYdnM4Jbat2wE7WtBletQyey5mIGvoT4Ix2A95fVyg&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=Pw0qL-yA0Ei5Tn7vuIAhLg&oh=00_AfGKgglpenacolfIuAcVtmpO6AlG9U4xei8m4ZPWT3BTQg&oe=681D89D1)