Cataloguing History: Why We Hold Specialized Auctions

Auctions offer a moment where the sometimes-incalculable significance of an object is quantified. The price is reached through collaboration: specialists, consignors, the market, and finally, bidders convene in the room, surface through the internet and dial-in over the phone on sale day. Auctions facilitate the process of describing the value of objects that may have been previously unseen or of unknown importance. That’s the intrigue of the auction market, as well as what makes specialized auctions so essential.

When a specialist catalogues an object, they tell its story. That story may include the author, artist, the persons who handled it, medium or title, association or edition. It may also involve describing the movement or moment from which that object emerged. Place a number of like objects together and a more complex story emerges. Limit a catalogue to a single subject or medium, cultural group or historical movement, and the specialist is able to draw connections that are possible only through the juxtaposition of these objects. This potential for storytelling is what distinguishes specialized auctions from the general. Specialist Lauren Goldberg of Vintage Posters said it’s “our way of bringing the rarest and best examples of a genre to the forefront.”

Much in the same way a boutique store tells you where to look for specific goods, a highly specialized auction also helps institutions and collectors know where and when to look.*

Identifying Areas of Expertise & Interest

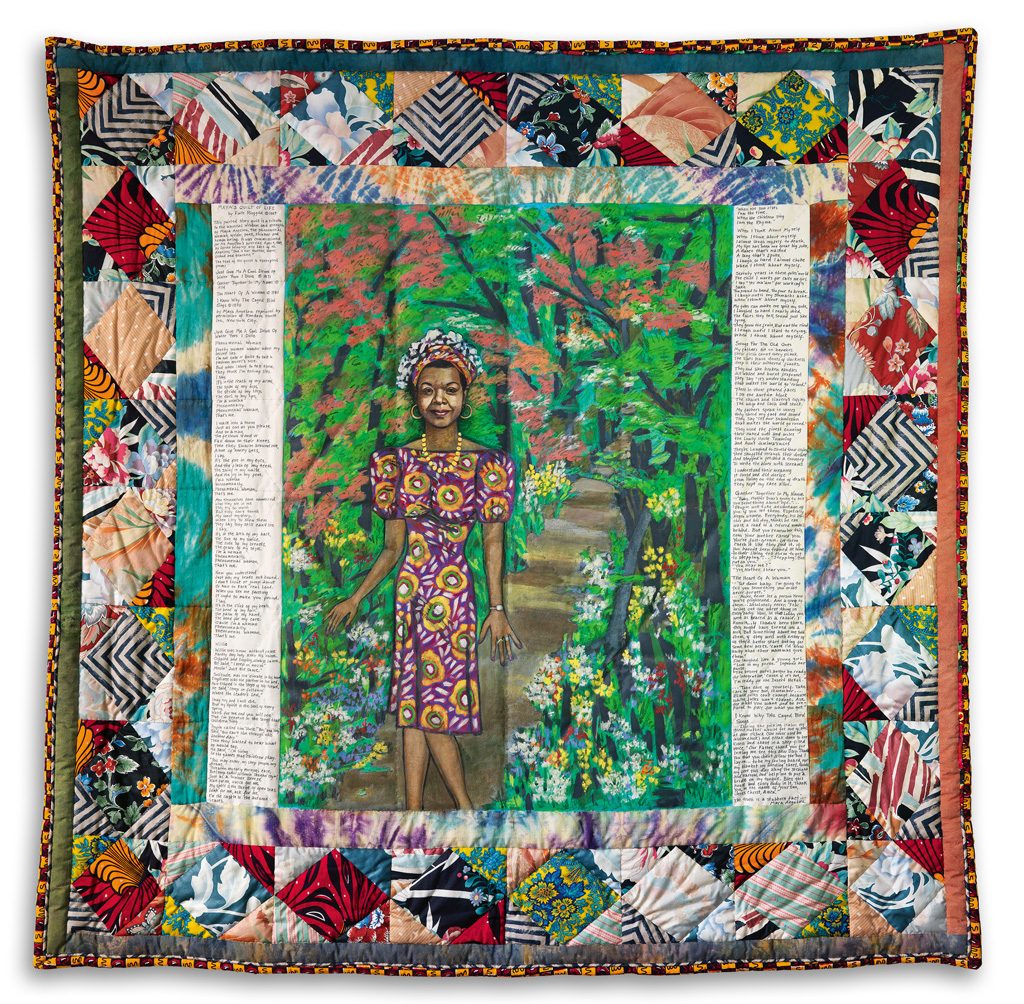

Following the arc of African-American Fine Art at Swann may be the most straightforward place to begin. Before Swann established a department for the material, institutions and collectors alike had to sift through reams of auction catalogues filled with work by primarily white, male artists with more established markets (think Chagall, Miró, Picasso) before they found a work at auction by an African-American artist.

Around the time that the internet made collecting from specific categories easier (thank you, keyword alerts!), our African-American Fine Art Director, Nigel Freeman, then a Specialist in the Prints & Drawings department, noticed that certain works by African-American artists were garnering a lot of attention during their more general sales. In response, he organized special sections within their larger catalogues to test the market. When those overwhelmingly succeeded, it was clear that there was an urgency to facilitate markets for these artists. Freeman says it “was a chicken-and-the-egg scenario, if it didn’t have an auction record, it didn’t have any value, even though they might have had significant careers” or carried cultural cache in the absence of official gallery representation. In 2007, Freeman launched the department, which, in just their first few years, introduced more than 100 artists to the market.

Cultivating a Market

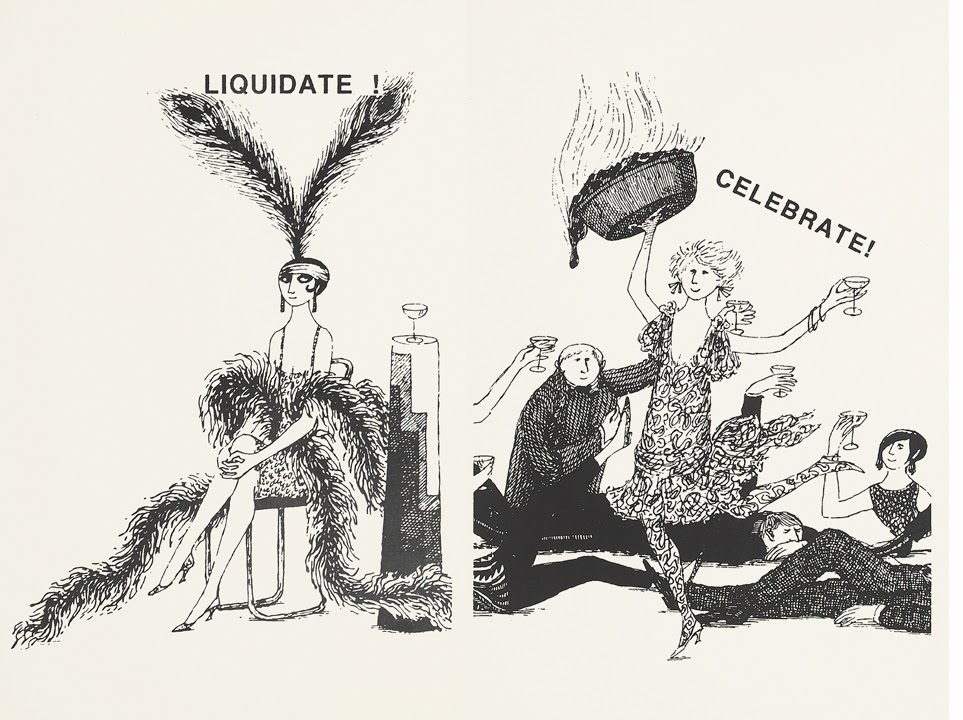

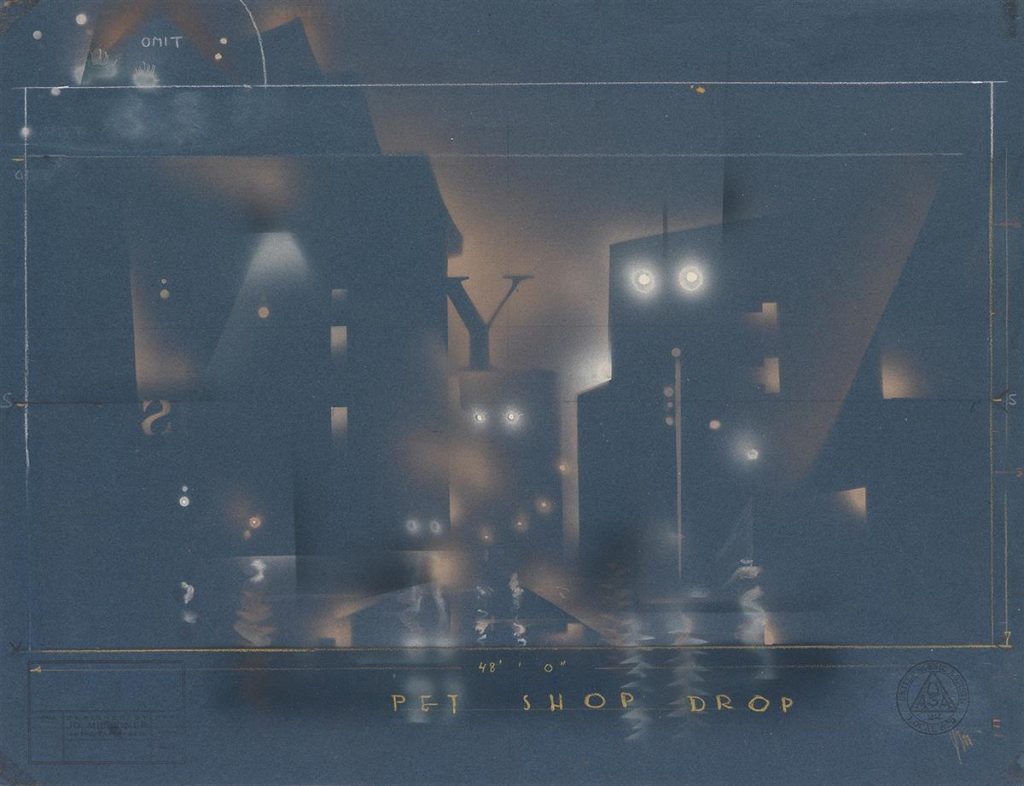

One of the benefits of having a breakaway sale is that specialists have more time to deepen their knowledge of the subject during their research period. For Senior Specialist Christine von der Linn, the choice to bring Illustration Art out of Books sales and into a category of its own was in response to a growing demand for original works of narrative art, and in doing so, they clarified the original pieces from their reproductions. Another effect the breakaway sales had was that they elevated a genre sometimes disparaged and seen as too utilitarian by the larger Art World to be Blue Chip. “Certain Golden Age illustrators–Parrish, Leyendecker, Rockwell–are pulled into American Art sales. Illustration Art was not always taken seriously, and so it’s an ironic twist that even though many were self-described illustrators, they now fit into the ‘American Art’ echelon.”

Over time, specialized auctions become traditions, for the house as well as the community of bidders that often attend each, keeping track of the material with each annual or semiannual sale. Book Department Director Rick Stattler also reaches out to the larger community – anywhere from “dozens to hundreds of institutions with each catalogue. If there is an invaluable archive of letters related to the people of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, I find out what museums or libraries in Oshkosh need to know about that material.”

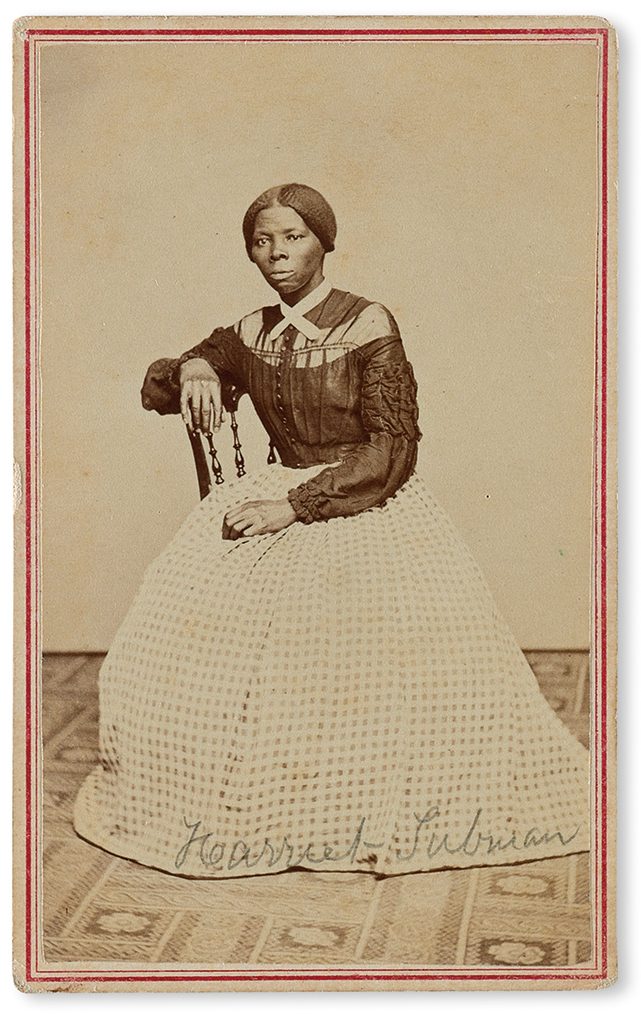

Each catalogue in itself becomes a point of record to which scholars often refer, Stattler said “because they’re systematized, the sales are public, and there’s a date attached to them. At every auction, we see bidders with copies of our catalogues all marked-up and dog-eared, which, as a cataloguer, is always nice to see.” After over 20 years of annual Printed & Manuscript African Americana events, remarkably, the catalogues themselves are now collectable.

Defying Category

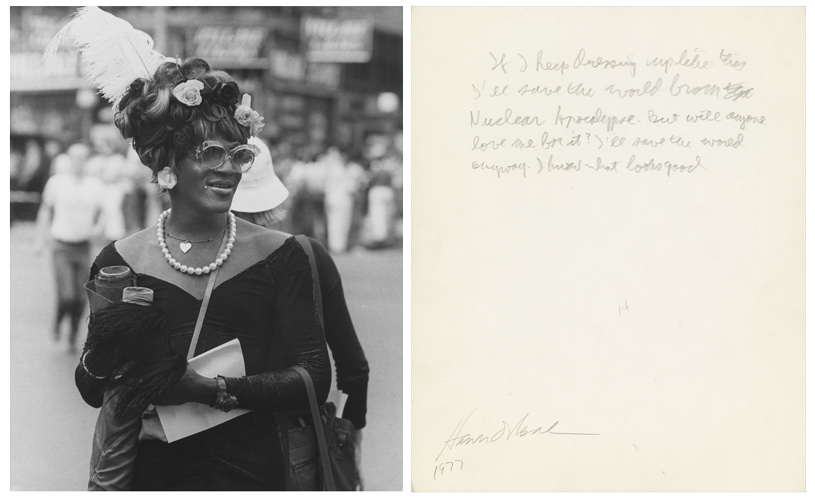

Many of the things that come through Swann come from complex histories. Their creators can be complicated or perplexing individuals with their own web of relationships, and sometimes the circumstances of their arrival at Swann could fill an entire book. Any number of factors can make it difficult to pin an item to a single auction, and this is the nature of the auction cataloguer’s responsibility. These factors are considered carefully along with the consignor’s wishes and our auction schedule, and the decision is based on which auction we think best honors the object and its historical legacy.

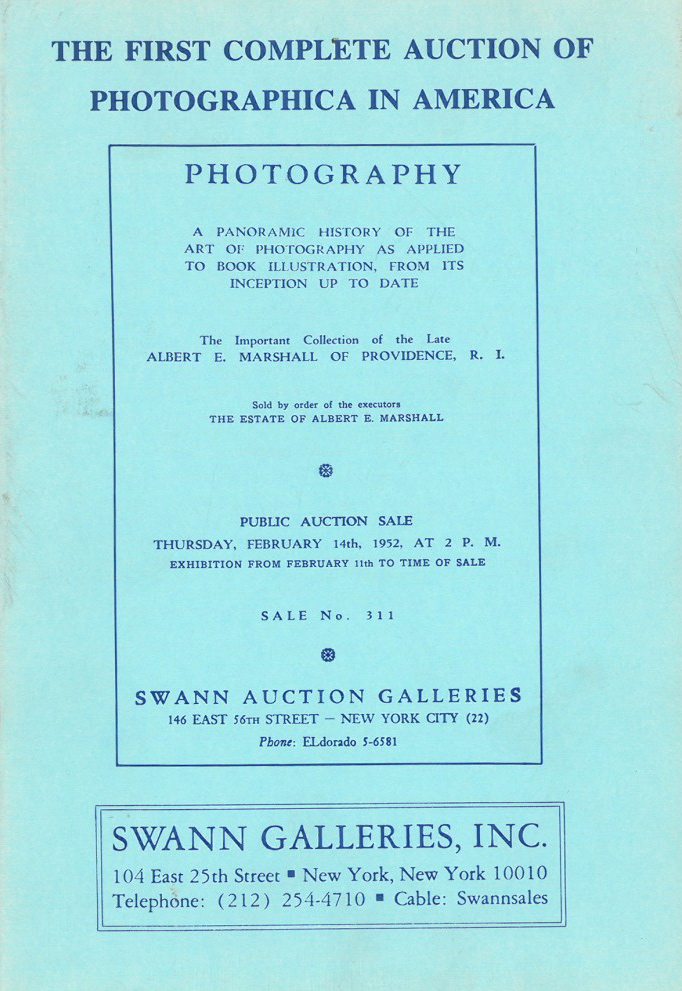

Swann is a family-owned business that began as an auction house specialized in rare and antiquarian books. Cataloguing is a labor of love, and specialists at Swann are encouraged to follow their instincts. One could say that the first truly specialized auction at Swann to think outside the box, at least in a historical sense, also happened to be the first auction in the United States dedicated entirely to photographs, in 1952. The Swann Printed & Manuscript African Americana and African-American Fine Art departments were founded 23 and 15 years ago, respectively, and the Illustration Art department took off in earnest 6 years ago. The first-ever auction dedicated to the material culture of the LGBTQ+ community, The Pride Sale, was held on June 20, 2019.

*Since the publication of this post Swann has added sales dedicated to the contributions of women to all areas of society and introduced categories dedicated to Latin American, Latinx and Chicanx art.