An Eighteenth Century Pye Recipe

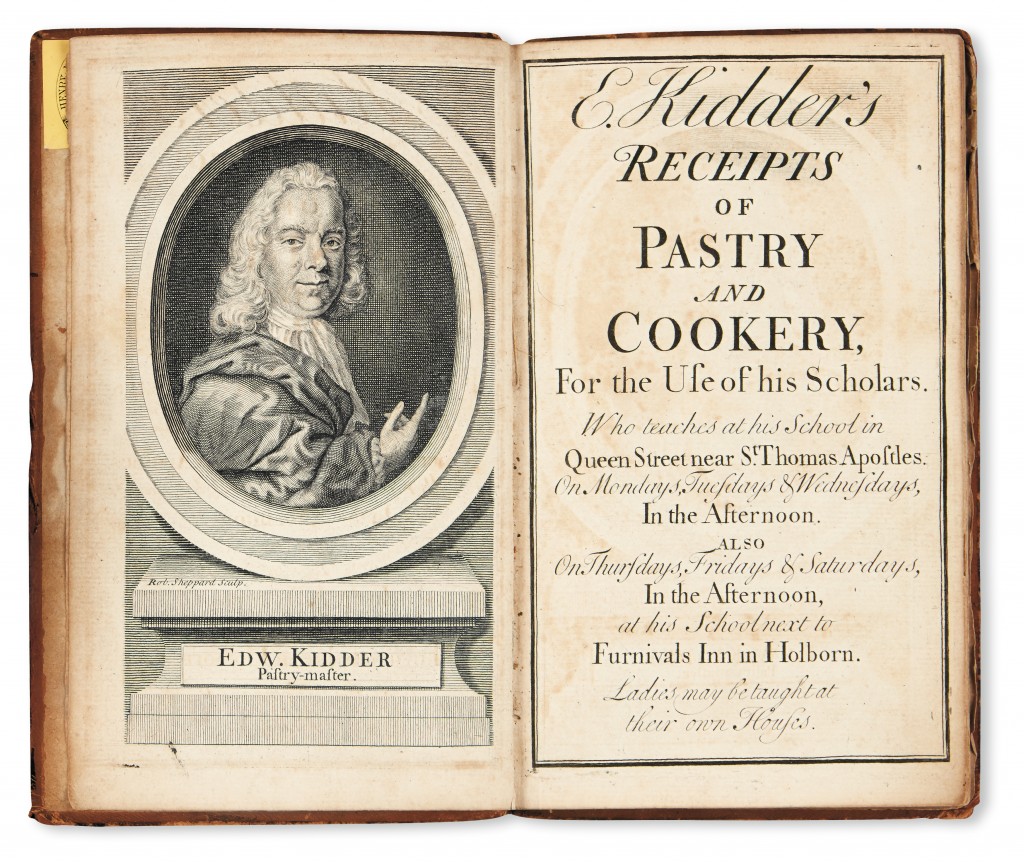

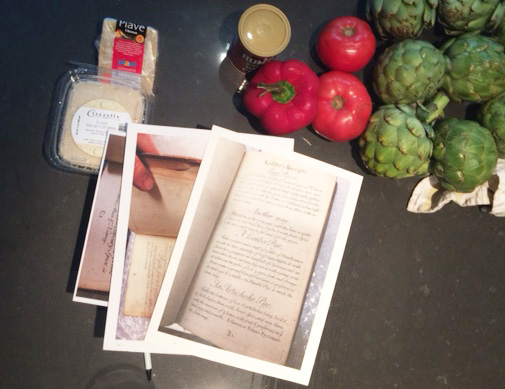

When recipe books come to Swann, the only thing to do is test them out. In our upcoming October 18 sale of Early Printed, Medical, Scientific & Travel Books is an unusual cookbook from eighteenth-century England. Edward Kidder’s Receipts of Pastry and Cookery provides instructions in the making of over one hundred “pyes,” puddings, and pickles.

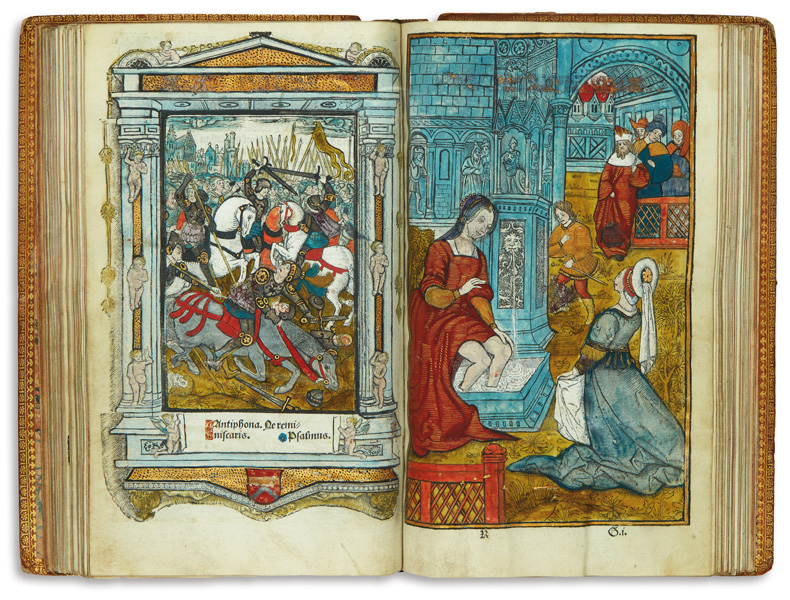

Edward Kidder ran a popular pie shop and baking school in London in the early eighteenth century. He published a recipe book to allow his pupils to recreate the pies in their own homes, as well as a sort of advertisement for his services. The book is beautifully printed with individually engraved pages, which Senior Specialist Tobias Abeloff remarked is highly unusual–by the 1700s, the vast majority of books were printed on a standard press with movable type.

Kidder, who called himself “pastry master,” was something of a celebrity chef in his day. The book includes the first published recipe for puff pastry, which we replicated exactly to make our pies.

Puff Paste

Lay down a pound of flower, break into it 2 ounces of butter & eggs: then make it into Paste with cold water: then work the other part of the pound of butter to the stiffness of your paste: then roul out your paste into a Square Sheet: Stick it all over with bitts of butter: flower it, and roul it up like a collar, double it up at both ends that they meet in the middle, roul it out again as aforesaid till all the pound of butter is in.

A fascinating part of this particular example is that there is a small handwritten inscription on the verso of the portrait from one woman to another. There is no other date given in the book, and scholarship cannot agree on the exact date of publication of Kidder’s Receipts. The inscription reads:“[illegible] her book February the 12th 1733/4 the day I began learning of Mr Kidder.” This gives us a clearer idea of when the book was first published.

The title page includes a note advising “Ladies may be taught in their own houses.” The book contains recipes for all sorts of things, but the bulk of the pages are devoted to pyes. Some of the recipes would be right at home in a modern cookbook, such as Mushroom Pye and Venison Pye. Others, like Battalia Pye, were almost too strange to read. There is even a Swan(n) Pye!

A Battalia Pye

Take 4 small chickens, 4 squob pidgeons, 4 sucking rabbits, cut them into pieces, season it with savory spice and lay them in the pye with 4 sweetbreads sliced and as many sheeps tongues, 2 shiver’d pallats, 2 pair of lamb stones, 20 or 30 cocks combs with savoury balls & oysters, lay on butter & close the pye A L ear.

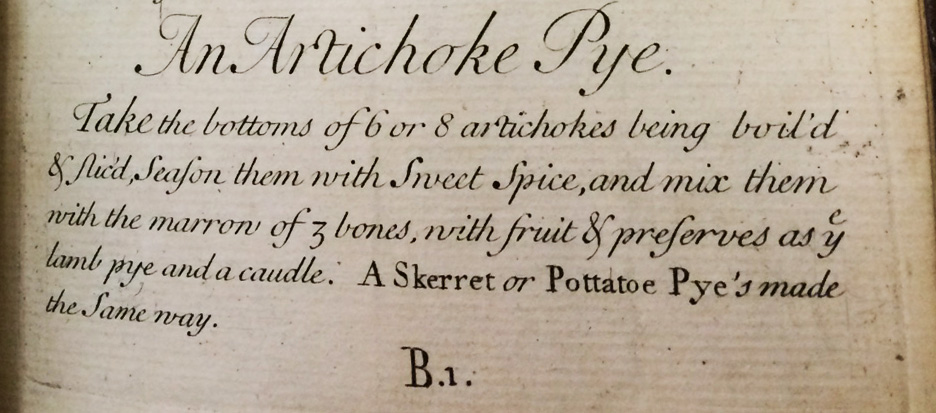

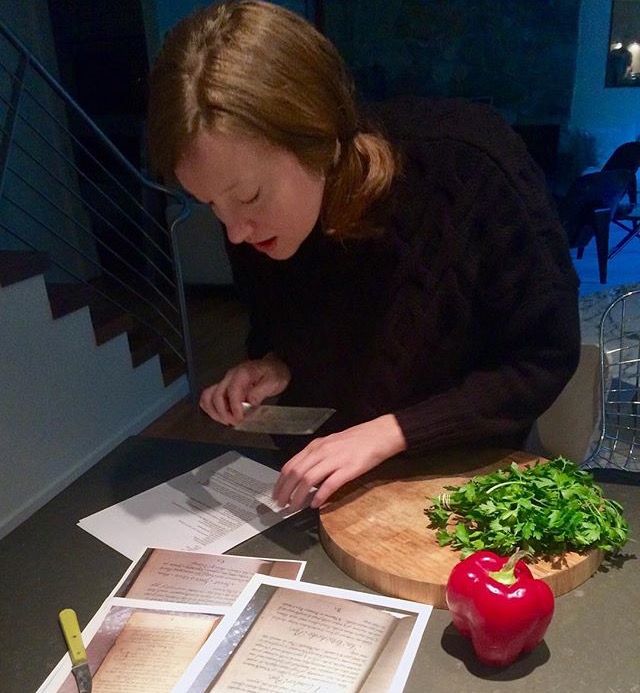

Communications Assistant Ferry Foster chose to do An Artichoke Pye.

Take the bottoms of 6 or 8 artichokes being boil’d & slic’d, season them with Sweet Spice, and mix them with the marrow of 3 bones, with fruit & preserves as ye lamb pye and a caudle. A Skerret or Pottatoe Pye’s made the same way.

The first step was interpretation. The recipe called for fruit: we figured that in 1733, “fruit” referred to any kind of edible vegetation, rather than the stricter definition in use today. The recipe also called for “Sweet Spice;” according to Kidder, Sweet Spice is cloves, mace, nutmeg, cinnamon and salt; if for meat pyes, fowls or fish with a little fine pepper. Savoury spice is pepper, salt, cloves, mace & nutmeg.

We found a modern equivalent to the recipe which would give us baking times and measurements, as well as some ideas for “fruit.” We chose a Mario Batali recipe because it seemed closest, despite having a recommended bechamel sauce.

We followed Kidder’s recipe for the crust (flour, eggs, butter); Batali’s recipe to soften the artichokes (fried, with onions); and Kidder’s mixture of spices (minus mace). At this point there was a disagreement about which recipe to follow: the fruit and preserves of Kidder, or the bechamel of Batali? We decided to make two pies.

The first pie followed Kidder’s recipe: we added red peppers (our “fruit”) and a savory chutney (“preserves”). We hadn’t found any bones or marrow, so we scooped in some bullion paste.

For the second, Batali pie, we cooked a creamy bechamel sauce with milk and butter and mixed it in with the artichokes, along with some parsley. We covered both pies with the rest of the dough and followed Batali’s directions for oven temperature and cook time.

Forty minutes later, we had two beautiful pies! The Kidder pie tasted sumptuous and medieval, as if we should have been wearing velvet robes and preparing to hunt a unicorn in the morning. The Batali recipe was warm and familiar, like a shepherd’s pie. Both were delicious.