Egon Schiele: A Look at the Artist’s Evolving Self-Image

Egon Schiele is celebrated among the Austrian Modern Masters Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka, who are best remembered for their insightful portrayal of the human condition. Schiele’s style was informed by the tumultuous nature of his tragically short life; in 1912 he was arrested and imprisoned on charges of kidnapping and seducing a minor, as well as displaying pornographic art. While the kidnapping and seduction charges were eventually dropped, he was convicted of the remaining pornography charge. His imprisonment, along with a period of social isolation, enforced Schiele’s self-image as a martyr for his craft. These experiences and opinions had a profound effect on Schiele’s work, which can be clearly perceived when looking at pieces crafted before and after his imprisonment.

While the Cubists were breaking down form in Paris, Schiele and his cohorts were embracing the figure in Vienna in order to expose deeper emotions and ideas. Turn-of-the-century Vienna was an incubator of intellectuals, fostering an environment of both academic and visual creativity. Visual artists, musicians, writers, philosophers and scientists were not segregated and greatly influenced one another through their interconnected circles. As such, Klimt, Kokoschka and Schiele confronted the most daunting corners of the human psyche in their work, playing off of the ideas they were immersed in and contributed to, including those of Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein and others. The rawness and sensuality of these artists’ work is what makes them stand out as some of the most meaningful and important objects of the early 20th century.

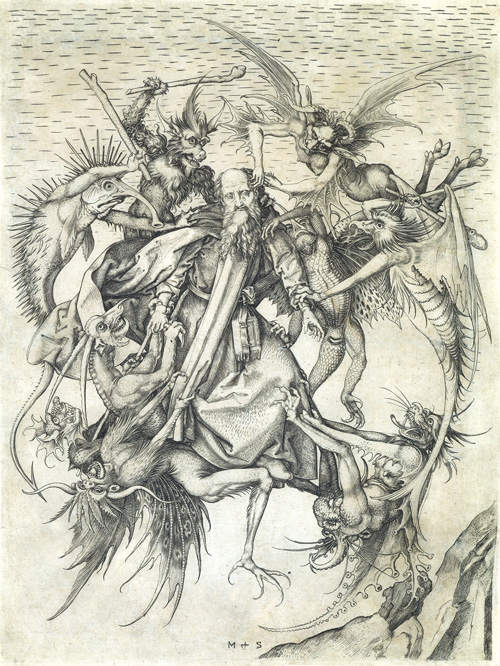

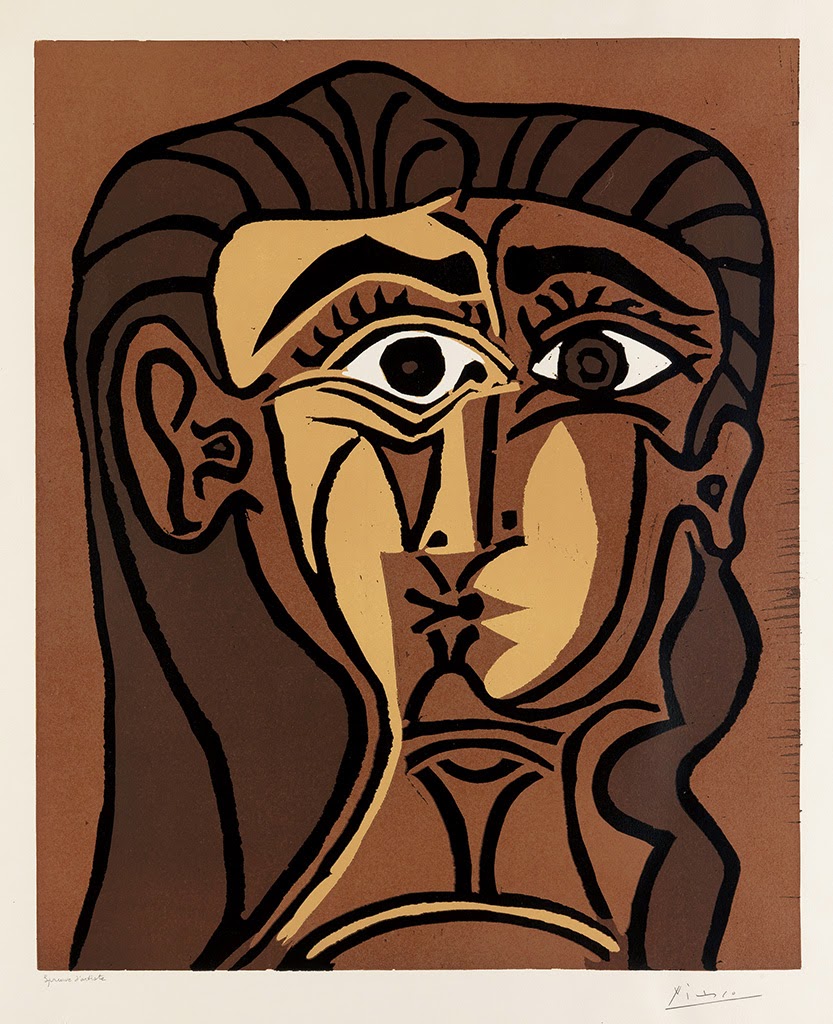

Schiele was heavily influenced by painter Gustav Klimt, whom he met in 1907 and took as his mentor. Klimt facilitated Schiele’s entry into the 1909 Internationale Kunstschau and afforded him connections to various wealthy patrons. The same year, Schiele and other young Viennese artists formally rejected academic tradition and started the Neukunstgruppe, prompting his family to discontinue financial support. Much of the apparent anguish in Schiele’s artwork stems from the critical and social isolation he experienced in the early 1910s and culminating in his 1912 imprisonment. The recent exhibition at the Neue Galerie, “Egon Schiele: Portraits,” curated by Dr. Alessandra Comini, brought renewed attention to Schiele’s drawings and focused on the imprisonment as a turning point in his work. We can see clearly the divergence in styles by comparing the artist’s pre-prison, 1910 watercolor Schlafender Mann (Sleeping Man) [pictured above], with the 1917 bronze, Selbstbildnis [below].

Fully realized watercolor studies by Schiele such as Schlafender Mann are extremely scarce as his career spanned only about a decade, and such compositions are important to the understanding of his overall development. Schlafender Mannis a stunning example of Schiele’s experimentation with color and line in 1910, a year during which he gave particular focus to studies of the male form. What is most striking is the electric blue hair and collar, exemplifying the artist’s deliberately avant-garde choices. The burnt red color in the sitter’s flesh is characteristic of Schiele’s work at the time, and though it is a clothed portrait the angularity in the figure’s limbs parallels the emaciated figure-type common in Schiele’s male nudes. The awkwardly crossed arms indicate a fitful sleep and allude to Schiele’s self-imposed mythology as a tortured artist, and the low perspective directs focus to the figure’s suggestively open legs, imparting ideas of eroticism, frequently seen in Schiele’s work.

Jane Kallir, Co-Director of Galerie St. Etienne and the author of Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, notes in the catalogue raisonné that the subject of Schlafender Mann has been identified both as a self-portrait and as a portrait of the artist Anton Peschka (1885-1940), who was a classmate of Schiele’s at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Art, a fellow member of the Neukunstgruppeand later Schiele’s brother-in-law. Schiele explored self-portraiture repeatedly over the course of his short career through drawings, paintings and sculptures, providing repeated imagery through which to examine his artistic processes. Whichever individual it depicts, Schlafender Mann is a brooding, self-conscious likeness that reflects the early state of Schiele’s career, as well as his general attitude toward artists at the time.

In comparing a drawing such as Schlafender Mann with a more familiar portrait that is seen regularly at auction and in museums, Selbstbildnis, we can see Schiele’s development pre- and post-imprisonment. In the sculpture, Schiele portrays himself harshly with a shock of hair and hollow eyes, as opposed to the more relaxed and calm Schlafender Mann. Selbstbildnis faces the viewer directly in a combative stance with a raised chin, asserting the artist’s confidence that had matured since his arrest, as well as his removal from society . As one of the few sculptures the artist created, a bronze cast from Schiele’s clay model, Selbstbildnisis a marked departure from his previous work. Unlike Schlafender Mann, the sculpture has a more permanent and (literally) weighted feel. Depicting his likeness in this way, Schiele further claims his dominance in the artistic sphere. Because the clay model was completed shortly prior to Schiele’s death, posthumous bronze castings such as this support the legacy he spent much of his career cultivating. Egon Schiele’s life and promising career were tragically cut short in 1918, when he succumbed to the Spanish flu epidemic at the age of 28. Spurred on by his experiences as outlaw and pariah, throughout his career Schiele rejected the norm and chose to apply a raw and emotional physicality to his work through his use of color, line, and gesture. Schiele is remembered today for creating some of the earliest Expressionist works in Austria, and for developing his own style independently of his Expressionist contemporaries across Austria and Germany. While Schiele is classified as an Expressionist, he forged a distinctive aesthetic that continues to set him apart from other artists.