247

●

(CIVIL RIGHTS.) SULLIVAN LEON.

“The Sullivan Principles” (supplied

title).

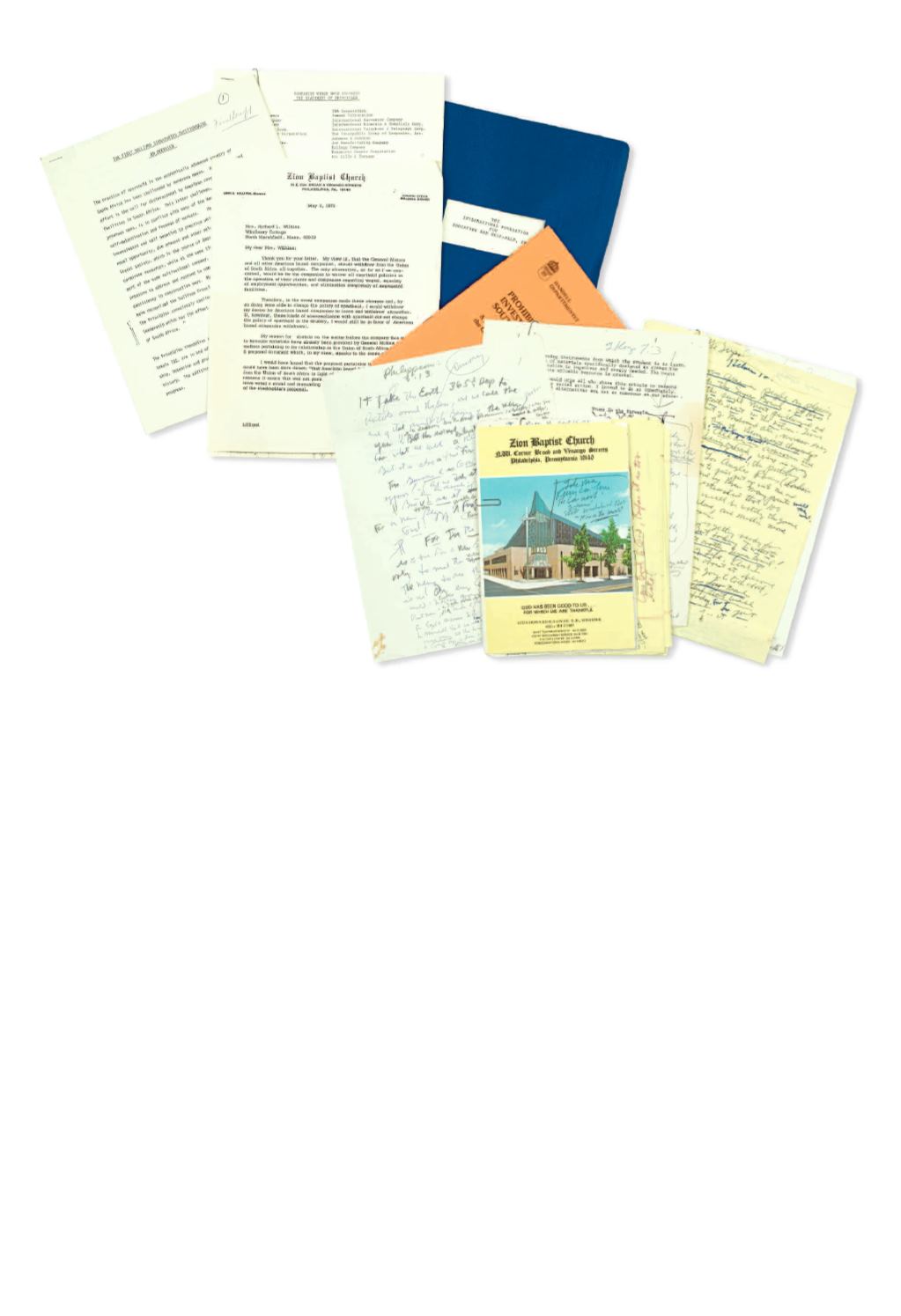

Large collection of printed and manuscript material including letters, printed and

manuscript speeches, sermons, flyers, photographs, correspondence to and from (with

retained copies).

SHOULD BE SEEN

.

Vp, 1970-2000

[4,000/6,000]

A RICH ARCHIVE OF THE PAPERS OF LEON SULLIVAN

,

BUSINESSMAN

,

BAPTIST MINISTER

,

CIVIL

RIGHTS ACTIVIST AND FOUNDER OF THE

“

SULLIVAN PRINCIPLES

.”

Leon Sullivan (1922-

2001), a truly remarkable man, overcame extreme poverty and the paralyzing grip of racial prejudice

to become a member of the board of General Motors, an ordained Baptist minister and powerful

activist for racial equality both here and in South Africa. There, the scourge of institutionalized preju-

dice, known as “Apartheid,” or separateness had kept millions of people in virtual bondage for nearly

a century. “Nowhere else in the world is found such [a] flagrant practice of man’s inhumanity to man.

. . . Ten years ago, I decided with the help of almighty God that I would try to do something about

the problem . . . these efforts became what are now known as the Sullivan Principles. . . “ Sullivan’s

nine-page manuscript speech with edits and corrections lays out his “principals” for South Africa.

Sullivan conceived of a domestic plan for communities here in America called the 10-36 plan, taken

from the parable of the loaves and fishes, and the community-based “Progress Plaza,” plan for a black

owned shopping center. Because of his unique position in the business world, Sullivan was able to

reach out to American business and urge them to withdraw economic support for the South African

regime. Leon Sullivan built what the Philadelphia Enquirer referred to as a business” Empire.” It was

through his holdings and connections that Sullivan was able to exert influence on the larger American

business world, to provide job opportunities here as well. It was Sullivan’s belief that education and

jobs were at the core of lifting up the African-American population as well as the African, and that

this could only be done through building and owning one’s “community.” There is a great deal of

material here relative to Sullivan’s business as well as his work in the African-American community,

with correspondence from an array of people in business, government and the Civil Rights organizations.