Guy Johnson on Maya Angelou

As I began writing this intro for Swann’s catalog, I realized that what I wanted to write was less about the pieces of art to be auctioned than about my mother and her relationship to art in general and what she taught me specifically.

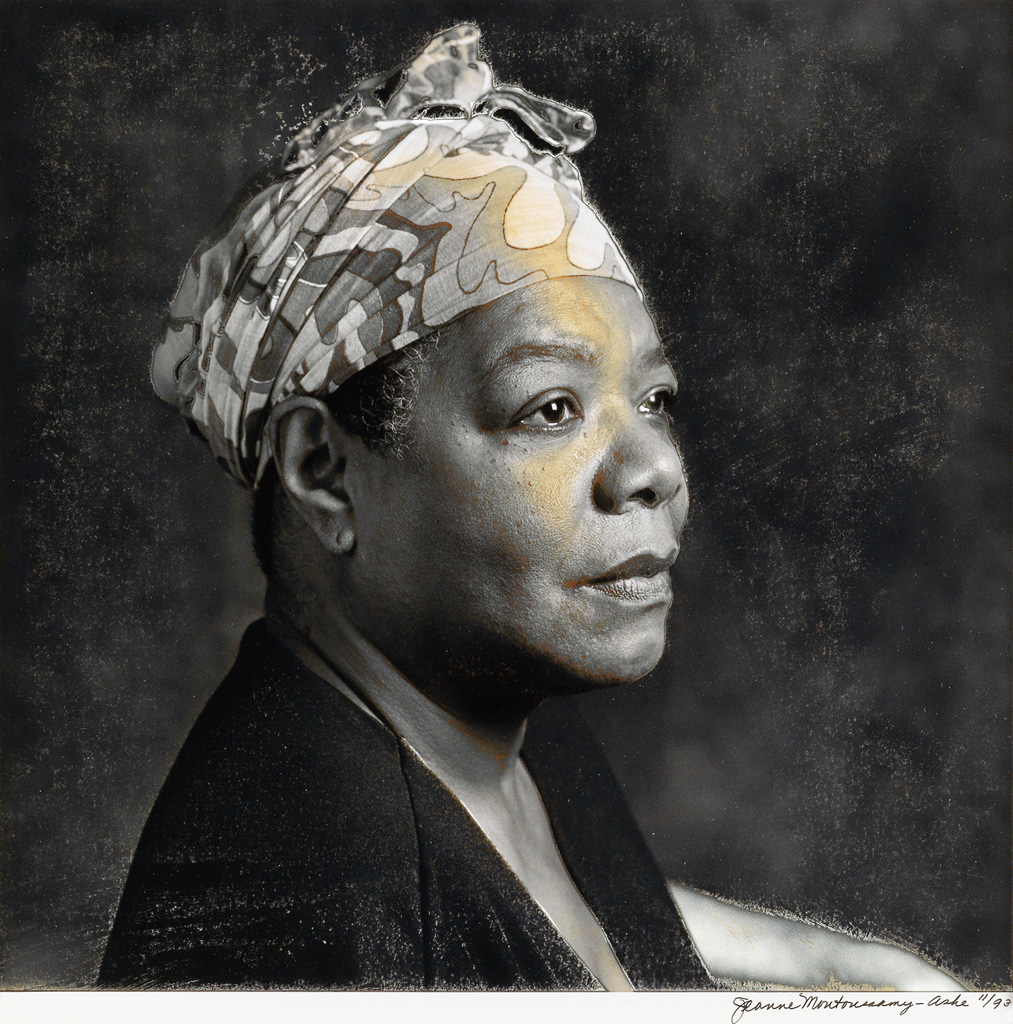

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Maya Angelou, silver print with and coloring, 1993. Sold for $17,500.

During my childhood, my mother always had prints from a wide range of artists hanging on our walls. Her tastes were eclectic, from Catlett, Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Charles White and Toulouse-Lautrec to Samella Lewis, Picasso, Wyeth and Degas. It was her belief that the presence of art and creativity in a person’s daily life broadened his or her perspective of the world around them. Truthfully, I spent a considerable part of my childhood, albeit unsuccessfully, trying to ignore the things my mother was teaching me. Until I became a teenager the art on our walls was irrelevant to me.

My mother and I moved to New York City in 1958 when I was thirteen or fourteen. We found a three bedroom flat in a brownstone in the Crown Heights District of Brooklyn. My mother was still singing in nightclubs and giving private dance lessons at the time, so the third bedroom served as her music room and dance studio. When my mother had a singing gig, which normally lasted six weeks to two and half months, we lived well; while she was in between jobs we lived on a tight budget.

About a year after we moved to New York my mother began working for Dr. Martin Luther King, heading the New York office of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) Her duties were primarily fundraising and organizing. The hours were long and there were many times she worked weeks without taking a day off.

“Art is in the eye of the beholder, my son. Now, for you this particular exhibit may be speaking in tongues, but for another it may be prophesying.”

Money was always tight during her tenure with the SCLC. Sometimes she would not even take her full salary. She would often ask me, “What’s more important to you, the struggle for freedom, or your creature comforts?” I always responded, “the struggle for freedom.” I really couldn’t answer anything else. The television news was full scenes from southern cities in which peaceful demonstrators were being set upon by vicious police dogs or were being beaten to the ground with batons.

Even though I was just a teenager, my mother felt we were in a partnership together and that I had a right to chime in on things that affected our lives, so she asked the question quite often. It’s not that we ever went hungry when she was working for the SCLC, but we no longer had the money to go out and eat in nice restaurants or take day and weekend trips like we had when she had singing jobs. In order not to lose touch with me, my mother instituted a plan that we would spend one weekend a month together. Since there was rarely any extra discretionary money to spend, during the day we normally went to museums, or if the weather was nice we’d go to Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens or Far Rockaway for chili dogs. In the evenings we went to plays, dance venues or jazz clubs in which she had friends performing. When Leontyne Price was in town we went to operas. My mother seemed to know everybody.

By the end of her first year with the SCLC, I was extremely familiar with museums of New York City, particularly the Schomburg, the Brooklyn Museum, the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art along with the Museum of Natural History. On each outing, my mother took to pains to teach me about the painters and sculptors who were being exhibited. She encouraged me to read such books as Lust for Life and The Agony and the Ecstasy. I once asked her why we never saw the work of any of the Black artists in any of the major museums but the Schomburg and she replied, “...Because there are people in charge of these museums who set themselves up as arbiters of what is art and who are artists worthy of being exhibited.” I think I must have responded with something stupid like, “Well, if I had a museum I wouldn’t exhibit any White artist either.” My mother responded with one of her mantras (which I probably heard over ten thousand times as I was growing up) “Don’t be a prisoner of ignorance. Prejudice and hatred diminish not only their object, but their possessor as well.”

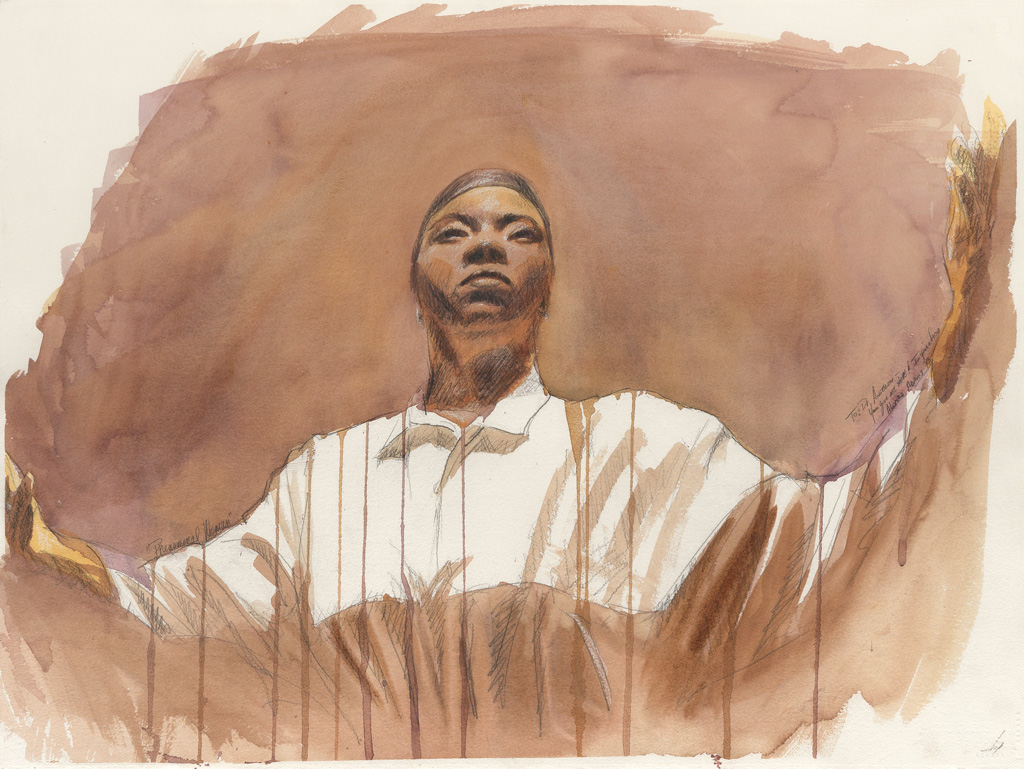

Alonzo Adams, Phenomenal Woman, watercolor and pencil, 1993. Sold for $10,000.

My mother never missed a chance to teach a lesson. There are some exchanges that you have with a parent that you remember somewhat sheepishly your whole life.

I recall one particular trip we made to the Museum of Modern Art and there was an exhibit called ‘White on White.’ It had received quite a bit of favorable press. It consisted of four paintings of different shades of a single white square on a white background. I was incensed that such work should be hanging in the Museum of Modern Art while the work of Black artists were being rejected. I think I may have declared something stupid like, “...This isn’t art! The arbiters were duped! This isn’t art! I wouldn’t hang this anywhere!” My mother gave me a long look then asked, “Oh, you should be the arbiter of art now? Out the billions of people on this planet, all of whom are different, you should be the one who determines what is art?” Once again, I was in abashed silence.

She continued, “Art is in the eye of the beholder, my son. Now, for you this particular exhibit may be speaking in tongues, but for another it may be prophesying.” I asked her what she meant and she answered, “When you speak in tongues, only God understands you. When you prophesy you create something that speaks to the common denominator of humanity; you create visions of what others may have seen, create feelings that others may have felt, describe experiences that others may have experienced.”

"Each piece she acquired spoke to her. She loved to sit and study her art and wonder what dreams or nightmares inspired the artist to create it."

Because I was as shallow as a saucer, I may have challenged her or questioned how her strange answer was manifested in life. I’ll never forget her answer. “When Van Gogh died in 1890 he had sold less than ten paintings. The people at the time didn’t understand his vision, yet over six decades later his work is prized and prints of his work are displayed everywhere. At the time he painted he may have been speaking in tongues, but for us living today he is prophesying. You must be careful not to disregard what you perceive as speaking in tongues. You have no idea whether the work will find relevance in the generations to come. I tell you now that it is my intent to prophesy, but that doesn’t mean there won’t come a time when people will think that I was speaking in tongues.”

For my mother, paintings, sculpture, dance and music were ways of translating the intangible into digestible bites; these forms of art were ways of expressing feelings and emotions that resisted the confinement of words. She appreciated a well-turned, lyrical phrase as much as the lines and contours of a well sculpted figure or the transcending brush strokes that accent an image or the ones that balance the composition of colors in a painting. If she saw a beautiful dance piece or heard a phenomenal musical riff or melody she would talk about it admiringly for days afterward. Imagination and creativity were the central pillars of her work life.

When my mother ascended she owned over five hundred pieces of art, consisting of paintings, sculpture and mixed-media. Each piece that she acquired, spoke to her. She loved to sit and study her art and wonder what dreams or nightmares inspired the artist to create it.

Her family hopes that the art which added color and character to her daily life does the same for others.

Catalogue Foreword by Nigel Freeman